Fools or Kings: who rules the world?

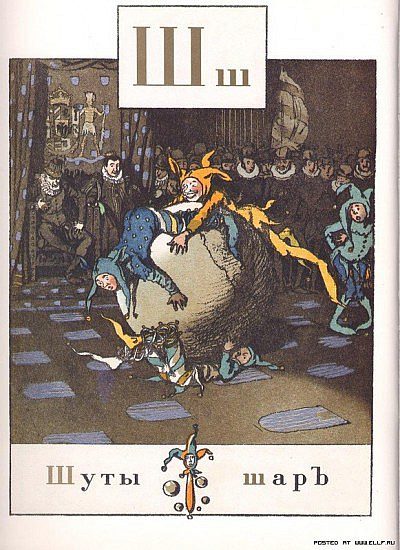

This page from Aleksandr Benois’ Alphabet Book illustrates the letter “sh” with fools or court jesters (shuty) and ball or globe (shar).

Four jesters: one leaping to power atop the globe, another pushed off the pinnacle, a third already deposed, flattened under the globe, while a fourth awaits his turn, as the world turns. The court looks on with curiosity; the King rather dejectedly.

Yuri Tsivian, a historian of Russian film, discovered that this is anything but a coincidental pairing of fools, worlds, and kings. It is a depiction of the medieval Wheel of Fortune. No, not the TV show, but an embodiment of the belief that political power is always fleeting, an image thought to derive originally from Roman philosopher Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy: “Are you trying to stay the force of her turning wheel? Ah, dull-witted mortal, if Fortune begin to stay still, she is no longer Fortune.”

The four Fools represent the four stages of rule: regnabo, regno, regnavi, sum sine regno (I will rule, I rule, I have ruled, I am without rule).

Illustration from John Lydgate’s Siege of Troy, showing the Wheel of Fortune held/turned by the Quene of Fortune. On the left, Dame Doctryne is accompanyied by two male figures, Holy Texte and Scrypture, and two female figures, Glose and Moralyzacion. They are shown helping people rise on Fortune’s Wheel because, Lydgate says, scripture is about that which shall fall (via Wikimedia Commons).

Tsivian was interested in the ways Sergei Eisenstein, the great Russian film maker, used Benois’ ironic Wheel of Fortune for depicting power in his 1940s masterpiece, Ivan the Terrible. That film was commissioned by Joseph Stalin in 1941 to glorify the Soviet Russian state and justify Stalin’s campaign of terror by portraying the 16c tsar as the founder of the Great Russian State, whose own bloody terror was justified by needs of that state. It was a commission dripping with irony, which was not lost on Eisenstein, who depicts Ivan as increasingly immobilized by his increasing power.

There is no better illustration of the impermanence of power than the current news from Ukraine and Russia. As American readers struggle to understand Russia’s fraudulent, ahistorical claim to Crimea, it is worth remembering that the territory under dispute has been the subject of dispute for centuries. All the more reason to have –and respect on all sides–clearly defined international agreements establishing sovereignty, because Boethius’ Wheel of Fortune is inexorable and Kings are Fools who forget:

“I turn my wheel that spins its circle fairly; I delight to make the lowest turn to the top, the highest to the bottom. Come you to the top if you will, but on this condition, that you think it no unfairness to sink when the rule of my game demands it.”

You can find Yuri Tsivian’s article on Benois and depictions of power, “Ivan the Terrible: Eisenstein’s Rules of Reading,” in Eisenstein at 100: A Reconsideration, edited by Al Lavalley and Barry Scherr (2001)

You can read more about Benois’ Alphabet here and here on Harvard’s Houghton Library blog.

And you can see the whole book here

On the changing fortunes of Ukraine and Crimea:

Andy Straw’s NEP blog, “The Tatars of Crimea: Ethnic Cleansing and Why History Matters.”

Kate Brown, A Biography of No Place: From Ethnic Borderland to Soviet Heartland

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin