By Jean Cannon

Research Associate, Harry Ransom Center

Among the first and most acute observers of the First World War and its impact on individuals were the British trench poets. Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, and others half-mockingly referred to themselves as “Recording Angels.”

As one of the curators of The World at War, 1914-1918, I conducted extensive research in the Ransom Center archives of British trench poets including Owen, Graves, Edmund Blunden, and Siegfried Sassoon, among others. One of my most jarring discoveries was that official wartime censorship—carried out by the military, the War Office, and the press—coincided with the self-censorship that psychiatrists of the time identified as a major contributor to shell-shock and to the disillusionment expressed by combat veterans. The archival record captures the military’s desire to mask the locations of troops. When writing letters home, for example, soldiers were encouraged to obscure their whereabouts with the now well-known phrase “Somewhere in France.” But the archives also testify to soldiers’ ingenious efforts to subvert such measures. While researching in the Wilfred Owen and Edmund Blunden archives, for example, we found out that Owen had embedded secret codes in his letters in an attempt to communicate his position to his worried family. When Owen used the word “mistletoe,” the second letters of each word in the following lines would spell out his position. We found one letter in Owen’s archive that ominously spells out “S-O-M-M-E.”

The Royal Irish Rifles in a communications trench on the first day on the Somme, July 1, 1916 (Wikimedia Commons)

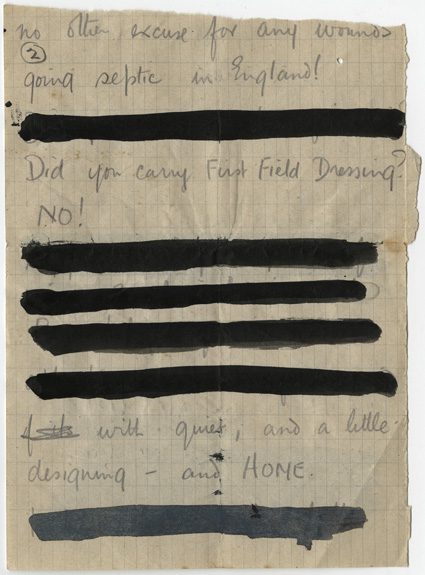

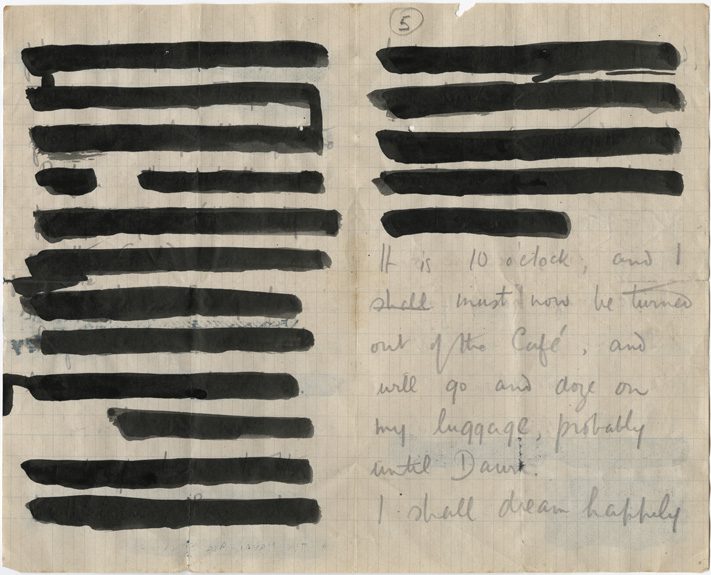

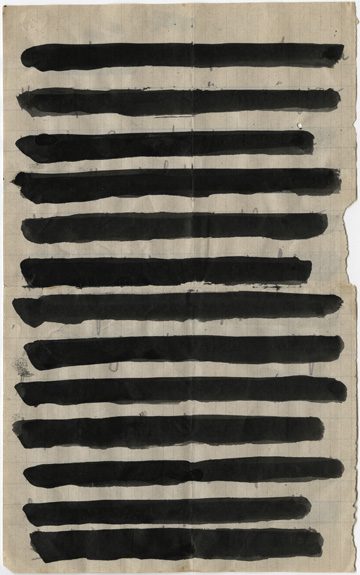

Perhaps the most heartbreaking evidence of censorship we uncovered dates from the post-war years. Before agreeing to publish the letters of his brother Wilfred in 1967, Harold Owen took India ink to the collection of correspondence that he had received in the years leading up to Wilfred Owen’s death on the Sambre-Oise canal barely a week before the cease-fire. The Owen archive therefore houses more than a dozen heavily redacted letters, which appeared in the Collected Letters with misleading placeholders such as “one page illegible,” masking the fact that Harold, rather than water damage, or mud, or bad penmanship, was responsible for making some sections unreadable. Wilfred Owen, who desired so badly to communicate with his family during wartime that he resorted to cipher, was later silenced by the friendly fired of his brother’s heavy redaction.

Why did Harold Owen censor his brother’s letters? In his autobiography, Journey from Obscurity, Harold indicates that he redacted the letters in order to protect the privacy of family and friends who were mentioned in the letters. But can we trust that this is true, or the only reason Harold Owen had to censor his brother’s letters? In 1917, Wilfred Owen was diagnosed with shell-shock and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital, where he met fellow poet and mentor Siegfried Sassoon, and wrote some of his most affecting poems. Very often during the First World War soldiers who “broke down” during or after combat were simply considered to be suffering from cowardice, rather than what we know as post-traumatic stress, and were accused of being “scrimshankers” who malingered in psychiatric hospitals rather than returning to the fight. Was Harold Owen, protecting his brother’s reputation, hiding evidence of Wilfred Owen’s neurasthenia from public view? Like Sassoon, Wilfred Owen also had had homosexual relationships that—though it is doubtful he wrote frankly about them to his brother—might have brought his posthumous reputation under scrutiny.

No scholar has been able to read the letters of Wilfred Owen in full, as they were redacted before being made accessible to the public once they were acquired by the Ransom Center in 1969. But now, while working on The World at War, 1914-1918, we have been collaborating with University of Utah’s computer programming expert Hal Ericson, whose retroReveal software has allowed us to recover sections of the letters previously rendered unreadable. Ericson’s web-based image processing system works to uncover hidden text from obscurity, and it is our hope that one day we will be able to read all of the redacted passages of the letters that Owen composed during wartime. Visitors may see the humble beginnings of our project in a section of the gallery dedicated to explaining the various forms of censorship in place during the Great War. In a letter written to his mother from the front, Owen claimed that he “came out in order to help these boys—directly by leading them as well as an officer can, indirectly by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them.” Through our retroReveal project, we hope to help Owen finally achieve his wish in full.

Drawing from the Harry Ransom Center’s rich archives of diaries, literary manuscripts, letters, artwork, photographs, and propaganda posters, The World at War, 1914-1918 highlights the geopolitical significance of the war and its legacy, while also providing insight into how the conflict affected the individual lives of those who witnessed through the years 1914-1918. The artifacts on display illuminate an event that changed forever human beings’ relationships with violence, grief, history, faith, and one another.

The classic work on the trench poets and their memories of World War I is The Great War and Modern Memory by Paul Fussell

For more reading on World War 1, visit our Featured Reads page.

Pages from Wilfred Owen’s letters reproduced with the permission of the Harry Ransom Center.