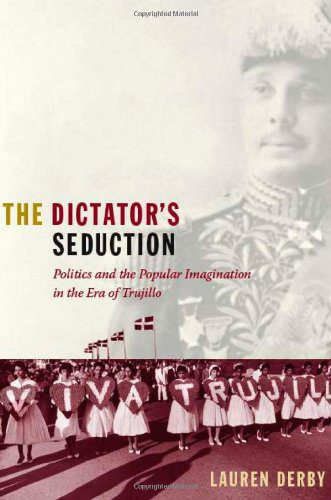

Rafael Trujillo, dictator of the Dominican Republic from 1930 to 1961, remains a figure of mythic proportions in the popular Dominican imagination.  A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.

Derby’s most salient observations of the populist dynamics of the Trujillo regime come through her examination of the ritualized practices of denunciation and praise and the tensions between the Dominican Party and an expanded state bureaucracy. Amongst ordinary citizens, state workers, and party officials, accusation reflected the Caribbean practice of gossip as a means of social control, while panegyric was used for personal gain. The conflict between the Dominican Party and an expanded state bureaucracy reflected this dynamic. Founded in 1930, the massive Dominican Party created a new, darker middle-class indebted to the regime for its new identity. State workers, on the other hand, continued to hail from lighter-skinned elite families. While this divide played on pre-existing socio-racial tensions, Derby demonstrates that Trujillo and his proxies also encouraged a culture of enmity between state and party officials. This left members of both groups vulnerable to charges of corruption, disloyalty, and moral failings, which could result in social death. In a culture sensitive to the loss of personal honor and respect, Dominicans lived in fear of social isolation. Moreover, state bureaucrats and Dominican Party workers used praise of Trujillo and their efforts on his behalf to improve their positions within the Trujillato and as a means of defense against condemnation.

The book’s most interesting claims emerge from Derby’s exploration of popular belief surrounding Trujillo’s invulnerability, which Dominicans attribute to his muchachito, or spiritual guide. After the assassination of Trujillo on the highway between Ciudad Trujillo and San Cristobal, the arranged coup failed to take place because conspirators inside the regime hesitated to believe that Trujillo, who had survived three previous assassination attempts, was dead. Derby shows that Dominicans attributed Trujillo’s invulnerability to his muchachito who purportedly visited Trujillo in his sleep. The muchachito found its roots in a popular mixture of Haitian voodun and Afro-Dominican vodú and was associated with black magic. It told Trujillo how to invest and about plots against him, providing a popular explanation of the apparatus of power. Popular Dominican religiosity viewed the duality of Trujillo and his spirit guide as extremely dangerous and unstable. Many believe that in the end Trujillo lost trust in his muchachito and challenged it. This loss of confianza led to Trujillo’s undoing. Derby also examines the rebuilding of Santo Domingo following Hurricane San Zenón, the coronations of his daughter at the Free World’s Fair of Peace and Confraternity in 1955 and his mistress at the Dominican Republic’s 1937 Carnival, clothing and tiguerage, and the growth of a grassroots religious movement called Olivorismo following Trujillo’s assassination.

Lauren Derby’s monograph makes a significant contribution to Dominican historiography and scholarship on populism, Latin American and Caribbean dictatorship, and gender and sexuality. However, while many of her conclusions are based on a series of oral histories, the voices of her subjects remain largely absent from the text. In addition, at times the work would have benefitted from a more in depth analysis of the complexity of race and national identity in the Dominican Republic. Overall, the text offers much needed assessment of popular culture in the Dominican Republic during and after the Trujillo regime.

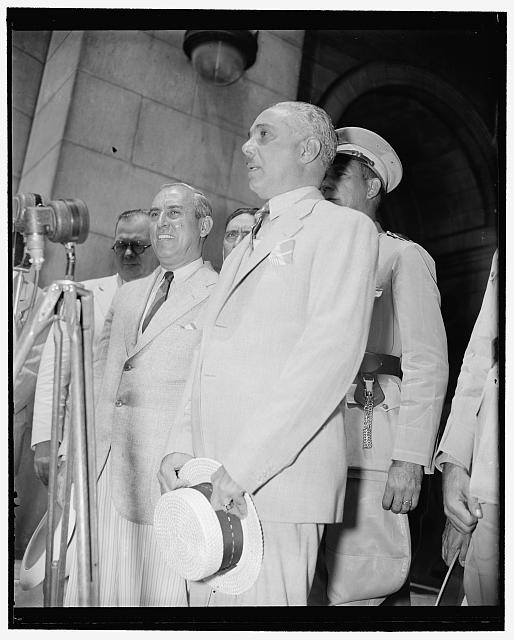

Photo credits:

Harris & Ewing, “Former President [of] San Domingo arrives in Capital. Washington, D.C., July 6. A close-up of General Rafael L. Trujillo, former President of the Dominican Republic, made as he stood at attention while the national anthem was being played upon his arrival today,” 6 July, 1939.

via The Library of Congress

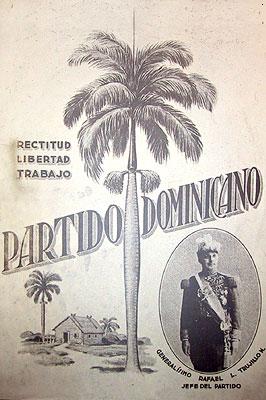

Unknown artist, “Insignia of the Dominican Party, the party founded by the Dominican dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo on 16 August, 1931.”

via Wikipedia

You may also like:

This interview, conducted in May 2011, with General Imbert, one of the men who assassinated Rafael Trujillo in 1961. (BBC News)

Adrian Masters’ review of The Doubtful Strait, Ernesto Cardenal’s poem chronicling the history of Nicaragua from colonial discovery to the Somoza dictatorship.