How can historians recover the nature and the significance of the interconnectedness of early modern Anglo and Iberian Atlantic worlds? One option is to study the maritime workers who laboured on the deep-sea sailing ships that were crucial to empire building and the expansion of capitalism during the age of sail (roughly 1500 to 1850).

How can historians recover the nature and the significance of the interconnectedness of early modern Anglo and Iberian Atlantic worlds? One option is to study the maritime workers who laboured on the deep-sea sailing ships that were crucial to empire building and the expansion of capitalism during the age of sail (roughly 1500 to 1850).

The crews of the deep-sea sailing ships that traversed the Atlantic Ocean in this era were “motley” or multi-ethnic. Sailors who were born in England and England’s North American colonies commonly toiled alongside people from many different parts of the world, including cities in the vast Spanish and Portuguese empires such as Cadiz, Lisbon, Cartagena de Indias and Lima. Native Americans and free and enslaved Africans also joined the maritime labour force.

In his latest book Outlaws of the Atlantic, Marcus Rediker argues that that sailors, pirates, and motley crews profoundly shaped the world they inhabited in ways that challenge nation-bounded histories or comparative approaches to studying the past.

Challenging the notion that elites were the early modern world’s only political theorists, Rediker contends that maritime workers invented many of the radical philosophies that gained currency in the Atlantic. He shows, for example, that a servant who had spent many years as a sailor and had voyaged to Brazil was the main source of information for the French philosopher Montaigne’s famous sixteenth-century essay, On Cannibals. The seaman’s account of the indigenous people who populated the New World shaped Montaigne’s declaration that Native Americans were not barbarians but “noble and dignified people” who deserved to be treated as such. Rediker says that it was not out of the ordinary for Montaigne to seek advice from a sailor. In fact, it was common practice for writers and statesmen to go to the docks to seek out lessons about distant parts of the world from the seamen who knew them best.

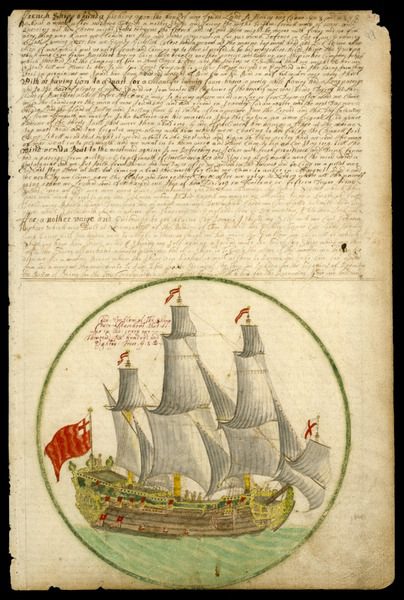

Rediker argues that the deep-sea sailing ship was a fertile ground for the formation of egalitarian and anti-authoritarian politics. Outlaws of the Atlantic uses a fascinating array of sources, including the seventeenth-century sailor Edward Barlow’s 225,000-word journal, to demonstrate that maritime workers developed a sophisticated class politics. Men like Barlow attributed their collective shipboard suffering of hunger, violent punishments, and fundamental lack of liberty, to the desire of powerful people to profit from the exploitation of the weak.

The ‘Cadiz Merchant’ under way, 1682 Plate from Edward Barlow’s journal of his life at sea in king’s ships, East & West Indiamen & other merchantmen from 1659 to 1703 ((National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK)

He shows that motley crews imagined and often tried to implement alternatives to their subjugation. Rediker considers the experiences of the thousands of seamen who became pirates in the early eighteenth century. He describes the pirate ship as a novel experiment in egalitarianism and democracy. Rejecting the hierarchy of a royal navy or merchant ship, pirate crews elected their own leaders and voted on important decisions. Rediker also shows that slave ships could be sites of resistance where enslaved Africans revolted against those who were transporting them across the ocean in chains.

In the second half of the eighteenth century sailors, pirates and motley crews became “the driving engine of the American revolution.” In the 1740s maritime workers led mass riots in North American port cities that attempted to stop the abhorrent practice of impressment, or of forcibly recruiting people into the royal navy. Rediker argues that these protests transformed political discourse and political strategy. For example, after witnessing these riots, Samuel Adams Jr. developed a new “ideology of resistance, in which the natural rights of man were used for the first time… to justify mob activity.” The violent tactics that sailors used in impressment riots, such as attacks on naval property, were later used in protests against the Stamp Act later in the 1760s.

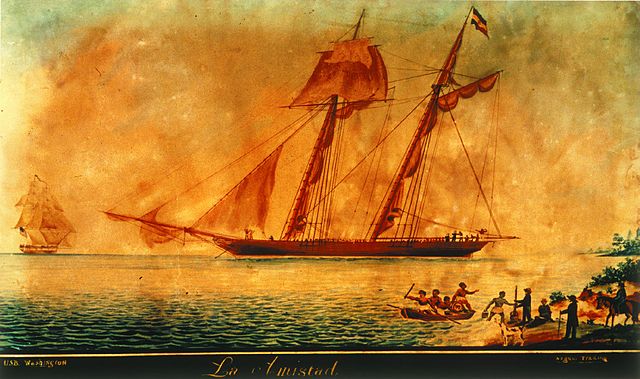

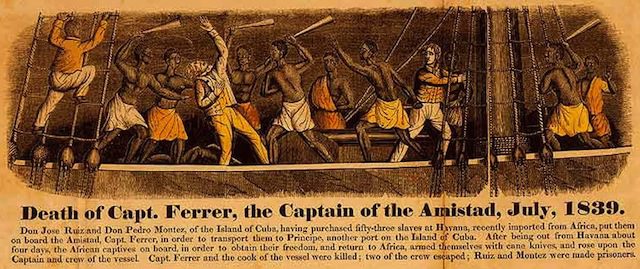

It is in Rediker’s discussion of Atlantic outlaw culture that we most clearly see the entanglement of the Anglo and Iberian and Atlantic worlds from below. The final chapter of this book sheds light on North American popular responses to the 1839 Amistad rebellion. Rediker presents fascinating evidence that working-class New Yorkers celebrated the Mende slaves who revolted against their Spanish masters on board the Amistad as heroic black pirates. In the city’s poor Bowery district, men and women flocked to see plays that praised the uprising. Printers wanting to profit from the popularity of Joseph Cinqué, the leader of the rebellion, published highly sought-after engravings that depicted him as a handsome, strong, brave, and confident man. For the growing multi-ethnic proletariat in North America’s bloating cities, “the autonomous, armed men, many of them black, inspired… not fear but hope.”

Color Engraving and Frontispiece from John Warner Barber (1840). A History of the Amistad Captives. New Haven, Connecticut 1840, via Wikimedia Commons

Outlaws of the Altantic leaves us wondering, did the cult of Cinqué spread beyond North America? Did Cubans and Mexicans also celebrate the feats of the black pirate? Rediker’s research would lead us to assume that maritime workers spread the story of the Amistad rebellion throughout the Atlantic world and beyond. This book sets the stage for further studies of anti-authoritarian proletarian traditions that ran across and beneath nation-states and empires.

Marcus Rediker, Outlaws of the Atlantic: Sailors, Pirates, and Motley Crews in the Age of Sail (2014)

You may also like:

Marcus Rediker’s wonderful explanation of the Frantz Zéphirin painting he used on the book cover.

Marcus Rediker, The Slave Ship: A Human History

Kristie Flannery, Sixteen Months in a Leaky Boat

Ernesto Mercado-Montero reviews Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profits (The University of Georgia Press, 2012) by Kristen Block

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott