The story of guaraná, the key ingredient of Brazil’s “national” soda and the centerpiece of a multi-billion dollar industry, may start here:

“In the ancestral village there lived a virtuous couple who had a young son. A performer of wonders, the boy, by the age of six, was revered by many. Like an angel of peace, surrounded by an aura of joy, the child put an end to feuding, maintaining the unity of his people. Abundant rain nourished plants that had once withered, begging for water. The sick were healed with the touch of his young hand.” So begins the Sateré-Mawé Indigenous community’s origin tale, set in the Amazon forest, as recorded by Brazilian military engineer João Martins da Silva Coutinho and published in Rio de Janeiro in 1870.

Roused by jealousy, however, the bad angel Jurupary plotted the young boy’s murder. One day, when the child climbed a tree, Jurupary transformed into a snake, grabbed him by the neck, and killed him. When the villagers found the boy, his visage was serene. Eyes wide open, he appeared to be laughing. But despair soon mounted as the boy’s death seemingly condemned the community to “eternal misfortune.” A sudden lightning bolt stilled the people’s cries. Then the boy’s mother spoke: “Tupã, the beneficent [God], has come to console us from this great affliction, repairing the loss we have suffered. My son will be reborn as a tree that will be our source of food and union, curing us of all bodily ills as well. But it is necessary for his eyes to be planted. And I can’t do this, so you must, as Tupã has ordered.” With the villagers reluctant to tear out the child’s eyes, the elders drew lots. The community’s tears watered the planting as the elders stood guard. Several days later, the guaraná bush bloomed.

The plant’s eyeball-like berries signified the boy’s resurrection and the genesis of a Native Amazonian people. The Sateré-Mawé refer to themselves as the “children of guaraná,” a botanical creeper native to the Brazilian Amazon that the Indigenous people first domesticated, as recounted in their creation myth, and whose seeds chemists have shown to contain between two to five times more caffeine than Arabica coffee seeds.

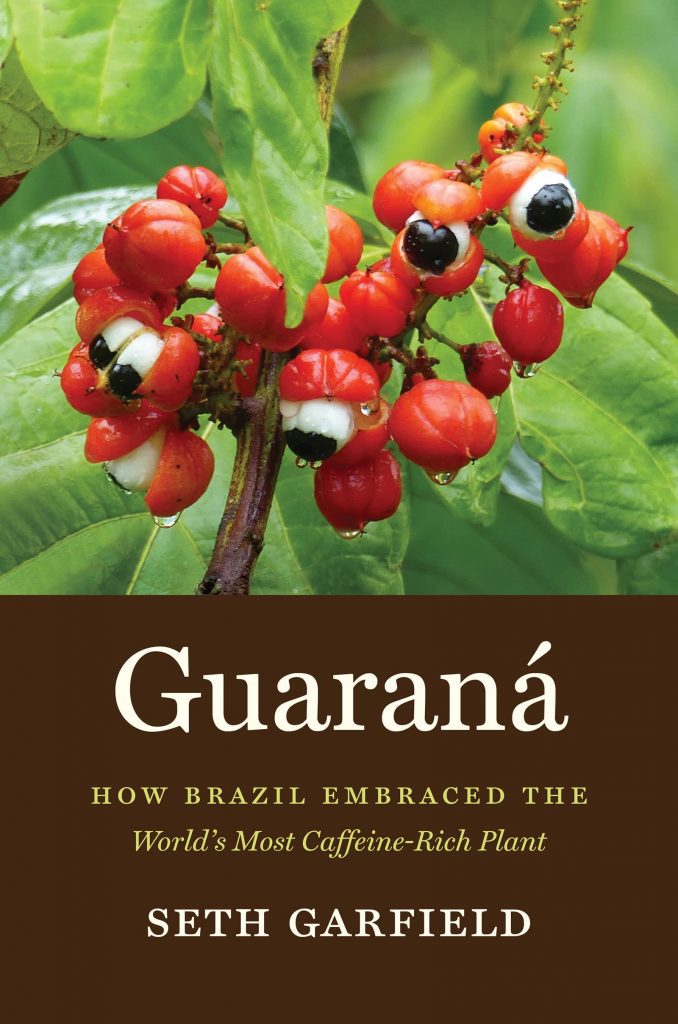

My book, Guaraná: How Brazil Embraced the World’s Most Caffeine-Rich Plant, charts the evolution of guaraná from a pre-Columbian cultivar and ritual beverage of the Sateré-Mawé in the Lower Amazon region to the headline ingredient of Brazil’s beloved “national” soda. Although guaraná is an icon of Brazilian national identity, we have lacked a monograph in either Portuguese or English dedicated to the history of the plant and beverage. A longue durée account of the plant’s domestication, appropriation, and circulation can elucidate the complexity of Brazilian history and society and the resilience of its Indigenous populations.

With their analeptic qualities, stimulants have long been valued commodities worldwide, yet psychoactive substances have their own distinct trajectories, applications, and cultural meanings. Guaraná is commercially grown only in Brazil, although no longer primarily in the Amazon region. Its principal market is the soft drink industry. It is also consumed as a syrup (notably, mixed with another Amazonian superfood, açaí) and in powdered form serves as one of many traditional phytotherapies embraced by Brazilians unable to afford or trust industrial pharmaceuticals–with an added popular reputation as an aphrodisiac.

The mass consumption of guaraná in Brazil stems in part from its high caffeine content, but also from the boosterism of missionaries, government officials, scientists, physicians, and marketers who touted the plant’s therapeutic benefits, “exotic” Amazonian origins, and nationalist cachet. Guaraná possessed, so they claimed, a dazzling array of attributes.

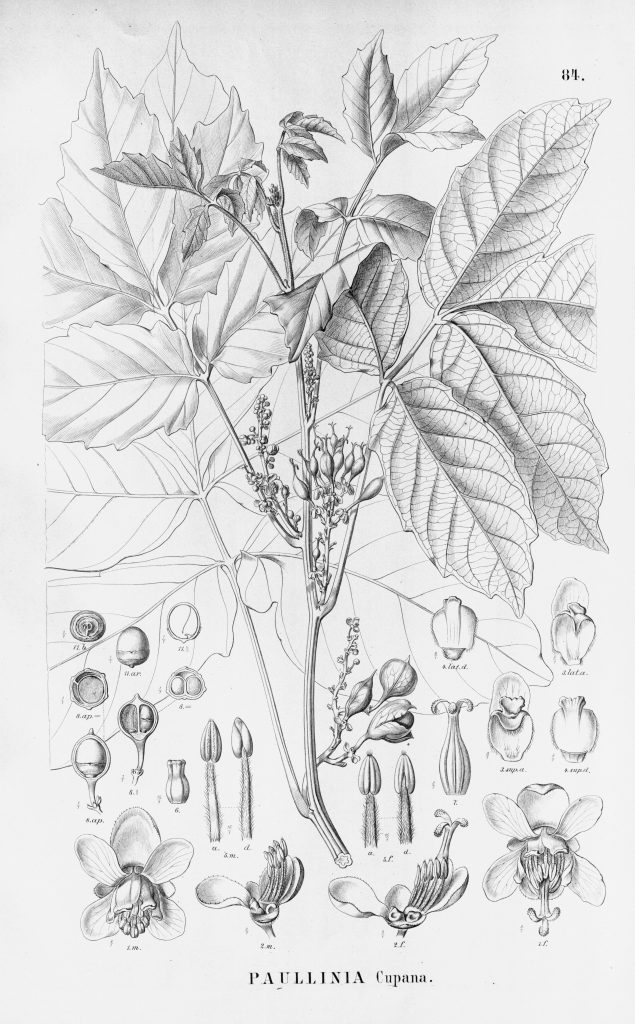

early nineteenth century, in Karl von Martius’s Flora brasiliensis (1874–1900). Although

illustrations of plants are ancient, Linnaean-style drawings aimed to depict the discrete

parts of a plant for the purpose of comparison and botanical classification. Such images

facilitated the exchange of knowledge of guaraná in scientific networks. Peter H. Raven

Library/Missouri Botanical Garden.

In the late seventeenth century, Jesuit João Felipe Bettendorff provided the first written account of guaraná’s physiological effects. The documentation reflected the missionary order’s oversight of Indigenous resettlement and intercultural exchange in the colonial Amazon and the Portuguese empire’s prominence in the global commercialization of medicinal plants in early modern history. In the nineteenth century, engineer Silva Coutinho moralistically touted guaraná as a commercial crop needed to secure the sedentarization of Indigenous peoples and the ”orderly” development of the Amazon. Positivist physician Luis Pereira Barreto, who devised a method to extract the syrup from the dried seeds for use in Brazil’s budding soft drink industry in the early twentieth century while adding his voice to the nation’s temperance and eugenics movements, hailed guaraná’s capacity to extend life through the prevention of arteriosclerosis and protection of the gastrointestinal tract. Merchants in the Amazonas Trade Association extolled guaraná as a prophylactic against “the pollution of food and modern lifestyles.”

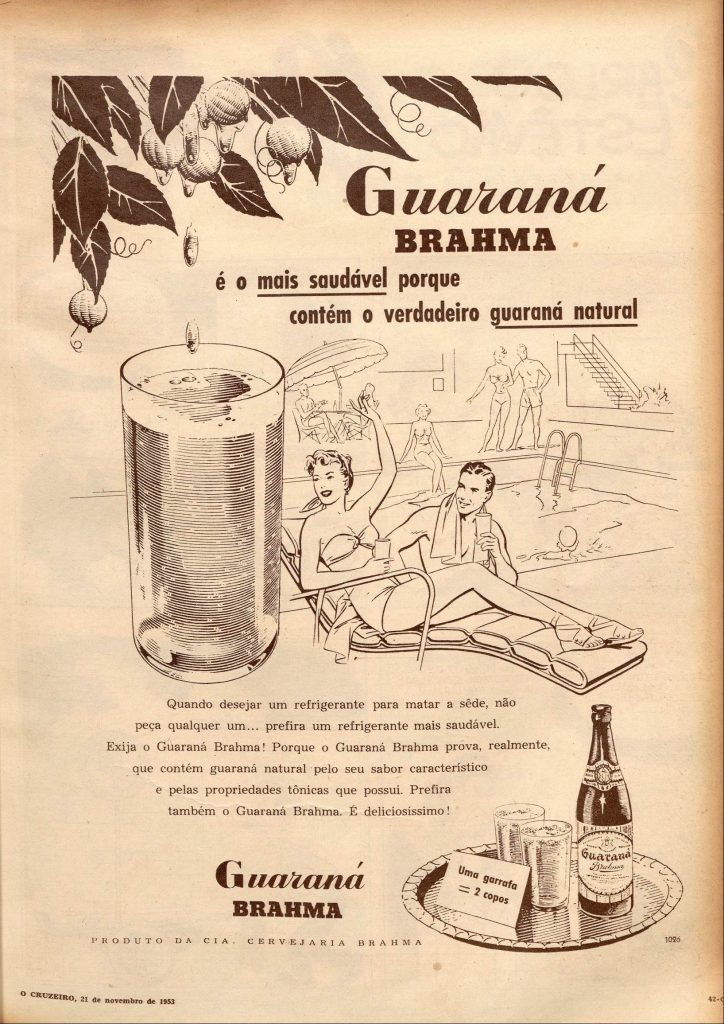

During the mid-twentieth century, advertisers and food columnists pitched guaraná soda as the beverage for the “modern” woman and homemaker, the delight of children, a remedy for physical vigor, and a marker of leisure. For city dwellers in the rapidly urbanizing nation, guaraná sodas offered not only a cool refreshment and quick energy boost, but also an alternative to risky water supplies. At the same time, the consumption of mass-produced branded goods signaled a new form of identity and communal belonging, a way of being “modern” and Brazilian. Indeed, for decades, advertisers pitched guaraná soda as an “authentic” Brazilian beverage, the fruit of a native Amazonian plant and the product of the nation’s multicultural heritage. This was in stark contrast with Coca-Cola, the Yankee interloper whose domestic manufacture dated to World War II and the provisioning of U. S. troops stationed in the geographically strategic Northeast region.

The historical itineraries of guaraná also offer an important lens onto Brazil’s Indigenous past and present. Over centuries of sustained Luso-Brazilian contact, the Sateré-Mawé were victimized by slavers, militias, and missionaries. They were cheated by traders swapping overvalued goods for guaraná for sale in frontier mining towns, and their control of the trade undercut by colonists who came to produce and market the drug, albeit of inferior quality. Indigenous scientific know-how was obfuscated or disparaged by botanists and chemists, who claimed that their quantifiable, standardized form of knowledge alone could establish the “universal” truths regarding the natural world. Pharmaceutical firms and soft drink manufacturers capitalized on Indigenous knowledge to make windfalls profits.

Yet the history of guaraná also reveals the Sateré-Mawé, like other Indigenous Brazilians, as more than victims. Consumption of their traditional guaraná beverage (known as çapó), linked to rites of passage, communal ceremonies, and political conciliation and decision-making, maintained the Indigenous people’s distinct sense of being in the world, while facilitating the acquisition of outside goods and knowledge that enabled them to weather the traumas of colonialism. They participated actively in the historical processes of exchange and integration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations that have co-produced scientific knowledge of the natural world. In 2014, the Sateré-Mawé population numbered 13,350, one of the largest of the 255 Indigenous groups in Brazil, who total 896,917 individuals, or approximately 0.47 percent of the nation’s population, according to the 2010 census. Defying Brazil’s agribusiness model and the global industrial food system, Sateré-Mawé communities market their guaraná today in Europe through Fairtrade and organic food networks and the support of Slow Food International.

Given that nationalist symbols of Brazil’s so-called racial democracy such as soccer, samba, and Carnival have generated ample scholarly attention, guaraná’s historiographical sidelining is noteworthy. Because guaraná never formed part of the slave-plantation complex, nor featured as a large-scale export commodity, the crop did not generate the trove of documentation of other Brazilian agricultural products, such as coffee and sugar. Unlike cocaine, opium, or marijuana, guaraná was never criminalized, sparing its consumers stigma and arrest, but excluding the drug from the vast documentation of state bureaucracies implicated in the coercive biopolitics of industrial capitalism and the racialized construction of vice in modern societies. And while the ingredient features today in energy drinks worldwide, guaraná soft drinks have not attained the fame of Coca-Cola, whose global brand recognition owes to U. S. political and corporate hegemony.

It is also the case that Brazilian historiography long marginalized or folklorized the nation’s Indigenous populations through narratives of cultural blending and physical disappearance. My book relies on environmental archaeology, missionary chronicles, naturalists’ accounts, nineteenth-century Brazilian government reports, biographies, Brazilian and U. S. pharmaceutical journals, proceedings of scientific symposia, newspaper columns, popular advertisements, and Indigenous myths and oral testimonies.

With mass production, what countless Brazilians have come to know as “guaraná” bears slight resemblance to the taste or function of the “real” thing. Or does it? Surely, nobody would confuse the flavor or the mode of consumption of the Sateré-Mawé çapó with guaraná soda. Yet, as I argue, the dominant society in Brazil likewise endowed a stimulating beverage with the imposition of order and meaning, the mediation of social contradictions and paradoxes, and magical powers of transformation. Consider a 1971 ad headlined “A soda free from the world’s evils” that reassured consumers: “In a world as artificial as this one, it’s incredible that there still is a soda this natural. Preserve what’s authentic in you. Drink Guaraná Brahma. The child of the jungles.” Or that from the underside of bottlecaps materialized refrigerators, bicycles, radios, and cars for a lucky winner.

My book subjects the belief systems, socioeconomic structures, and technoscience of Brazil’s non-Indigenous populations to the core cultural analysis traditionally reserved for Indigenous societies. As advocated by Bruno Latour, a “symmetrical anthropology” questions the so-called conceptual divides between nature and society, objects and humans, and things and signs said to distinguish “modern” from “premodern” societies. Conjuring an imaginary, non-material world in transforming commodities into signifiers of glory, advertisements are a particularly rich historical source. If magic in “traditional” societies tends to the unaccountable or the adverse, in “modern” societies advertisers channel feelings of anxiety and fantasy, firing the imagination through particular formulas and rites and inducing transformations to overcome uncertainty and perceived risk. Heeding Lévi-Strauss’s claim that the “civilized” and “savage” mind share the same basic structures of thought and classificatory disposition, the book further contemplates Latour’s insight: the “moderns” in Brazil merely have more specialists, resources, platforms, and networks to adapt and disseminate their guaraná product and its shape-shifting stories.

Histories of food and other day-to-day material objects have a unique way of reaching readers. This is in part, I believe, due to their immediacy. Moreover, they can open up multiple windows onto the past and contemporary daily life: on the realms of production, distribution, consumption, representation, affect, and identity formation. In other words, they enable historians to look at questions of embodied experience, status, hierarchy and power in society from varied perspectives. The many histories animating the “social life” of guaraná–as a feature of the anthropogenic landscapes, scientific experimentation, and cultural patrimony of Indigenous Amazonia; as a therapeutic treatment and object of commercial exchange for colonial Jesuit missionaries and nineteenth-century Western science and biomedicine; as a symbol of industrial food systems, mass consumption, and the nutrition transition in developing countries; and as a basis of myth and identity for the Sateré-Mawé and the dominant society–offer a taste of Brazil.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.