Simone de Beauvoir would not be surprised by #metoo. After all, she wrote the book that laid out just how profoundly women’s position as the subordinate Other warped sexuality, intimacy, and even love . The Second Sex, Beauvoir path-blazing 1949 work of feminist theory, did not mince words on what Kate Manne in Down Girl (2018) calls the “gory details” of women’s lived experience and their inequality. What is more, Beauvoir did not underestimate the difficulty of cutting through the knots of misunderstanding, incomprehension, complicity and denial that tangled relations between men and women. To dismantle deep structures of power would take inner transformation, stamina, real clarity of purpose, and it would require women declining invitations to “collaborate” – in our terms, refusing to latch onto class and racial privilege. Seventy-some years later, then, we are still contending with deep inequalities, sexism, and misogyny. Of course, Beauvoir might say: she had only explained how deep the problem ran.

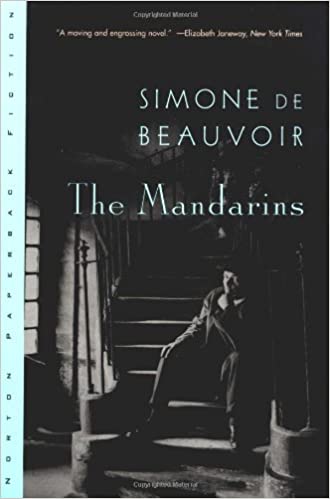

The Second Sex is only part of the Beauvoir story. The Mandarins, her 1954 novel about postwar politics, intellectual debates, and love lives of her circle of French existentialist thinkers made her into a literary celebrity. She went on to unspool her life story in four best-selling volumes of autobiography: Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1958), The Prime of Life (1960), The Force of Circumstance (1963), and the retrospective All Said and Done (1972). She brought readers along for her struggles as a writer, her travels, her politics, and her love life. These volumes were not a detour from philosophy. For Beauvoir, autobiography was a philosophical challenge: a reflection on freedom and one’s situation — and a very public process of self-discovery. Readers thrilled to it. Tens of thousands of women and men wrote to her to recount how, where, why and often with whom they had read her work, to endorse or argue with her ideas, excavate memories of historical events, to share dilemmas, and to puzzle through and interpret their own lived experiences.

I stumbled on these letters at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris when the collection was barely open and still being catalogued. They astonished me. They were vividly detailed, thoughtful, funny, eloquent, and direct –alternately admiring and irreverent. What an outpouring of projection, identification, expectation, disappointment, and passion! “For some reason I can’t explain, after reading this book I suddenly feel very close to you and feel the need to tell you that.” “Simone de Beauvoir, you belong to all of us, that is why I do not call you Madame.” “…you will cruelly disappoint me if you don’t give me the confidence or the support I expect.” I came to see how Beauvoir had invited herself into her readers lives. In The Prime of Life, she spelled out her ambitions as a writer. “What I wanted was to penetrate so deeply into the lives of others that when they heard my voice they would have the impression they were speaking to themselves.” It is a remarkable phrase. Small wonder countless readers cited it back to her, and that they felt summoned to think and feel with her, and to invite her into their lives. And small wonder that unlike many writers, Beauvoir saved letters from ordinary readers; they testify to the intensity of her bond with the public.

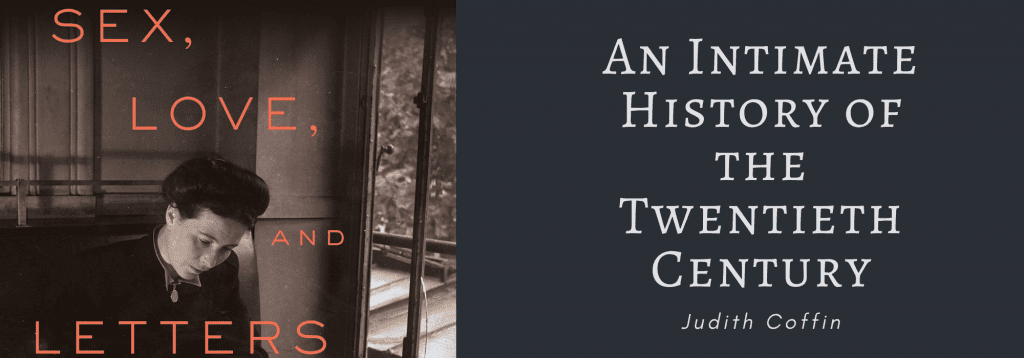

Sex, Love and Letters is based on this remarkable collection of letters. It follows this passionate and emphatically reciprocal relationship between author and reader from the publication of The Second Sex to the last volume of autobiography. The letter writers came from many different walks of life, and from men as well as women. Their missives arrived from across the world: Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Italy, Romania, the US and the Francophone world. As they wrote, these readers relived with Beauvoir the decisive developments of the postwar world: the efforts to grapple with traumatic memories of World War II, the Occupation and the Holocaust, the Cold War, the rapid rise of American cultural, political, and military power, an economic boom, decolonization. The letters take us through the inner turmoil of these tumultuous decades: we see the popularization of psychoanalysis and new theories of sexuality from a different perspective. The portrait of gender relations and politics is extraordinary. Readers reported on impossible marriages and families, confusing sexual desires, unwanted pregnancies, illegal abortions, and domestic violence in gory — and moving — detail. Many women wrote in anguish about their complicity in their situation, and their far from successful revolts against it. Their voices reveal much about the complexities of the sexual revolution and the volatile politics of feminism. They give us an intimate history of the twentieth century.

Simone de Beauvoir remains a polarizing figure: brilliant, fearless, and determined “not to miss anything of her time;” cagey and self-concealing, especially about her lesbian relationships. Was she blind to the distortions of looking at the world from a position of intellectual and white European privilege? Does she represent the radicalism of women’s liberation or its infirmities and limits?

She continues to attract a combustible mix of desire, resentment, and admiration. The letters at the center of Sex, Love, and Letters: Writing Simone de Beauvoir capture all these dimensions of her presence and legacy. More important, the book takes the spotlight off Beauvoir and turns it on the authors of these letters. As one wrote to Beauvoir, “What you lived in the spotlight I lived as an unknown, in the shadows.” These individuals are no less fascinating than Beauvoir. Their letters are a gripping portrait of everyday life and the politics of sex and gender. They are also testimony to the emotional and imaginative magic of books and letters, and a chapter in our ongoing love affair with memoir.

Judith Coffin is Associate Professor of History. She has written about gender, labor, sexuality, advertising, radio. You can find her work, here, or follow her on Twitter @judygcoffin.

Update: The Society for French Historical Studies awarded Sex, Love, and Letters the David H. Pinkney Book Prize. The citation is as follows:

Judith G. Coffin, Sex, Love, and Letters: Writing Simone de Beauvoir (Cornell University Press). Judith Coffin’s elegantly written book is a detailed portrait of the wide-ranging readership of Simone de Beauvoir through the letters that her readers wrote to Beauvoir. Coffin reveals the deep engagement that readers felt toward Beauvoir’s work, and ways that readers sought Beauvoir’s personal advice and political advocacy. Coffin’s deeply situated book shows how readers made sense of their lives, while also suggesting the ways this ongoing stream of correspondence affected Beauvoir. Coffin highlights what she calls the “public intimacy” of new forms of selfhood in the 1950s and 1960s, while also situating Beauvoir and her readers in the maelstrom of postwar reckoning with sexuality, gender roles, Vichy, Algeria, and postwar authoritarianism.

The article above is adapted from a piece that first appeared with Cornell University Press.

*Featured photo by Mihai Surdu.