Recently, the Texas State Board of Education faced a firestorm of protest, from conservatives and liberals alike, over the statewide adoption of textbooks for teaching history. On November 21, 2014, the Board approved the use of 89 social studies textbooks. This vote was the culmination of a long and contentious debate about what to include in — and exclude from — textbooks. Some conservative groups thought the books’ content was “anti-American,” contending that publishers shortchanged America’s accomplishments. Specifically, they wanted more emphasis on the beneficial economic impact of the free market and the role of Christianity among the Founding Fathers. Others thought that the textbooks already contained a deeply conservative (and flawed) interpretation of the past. These critics warned that they distorted, exaggerated, and ignored some tough truths about the American past. In her testimony before the education board, Dr. Jacqueline Jones, the Chair of the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin, said, “We do our students a disservice when we scrub history clean of unpleasant truths and when we present an inaccurate view of the past that promotes a simple-minded, ideologically driven point of view.”

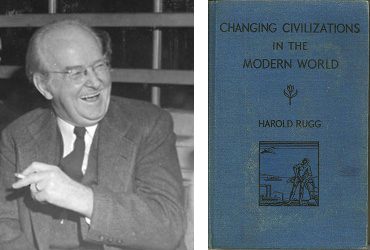

Public debate over the content of history textbooks goes back nearly 130 years, at least since the founding of the American Historical Association (AHA). In several reports in the 1890s, historians laid out a prescribed curricula for elementary and high school students. These initial reports received little criticism compared to what would come. Throughout the twentieth century, professors of history, teachers, parents, teacher educators, and other concerned citizens engaged in several high profile debates about the nature and purpose of history education in the nation’s public schools. One controversy from the 1930s about a popular textbook series created by Harold Rugg, a professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, provides historical context for what Texas just experienced in its debate over textbooks.

There are some similarities to the present-day — a struggling economy and calls for a more patriotic version of American history in our schools.The Great Depression and the Second World War witnessed dynamic curricular reform for history and social studies. After the stock market crashed in 1929, many Americans embraced what came to be called the social reconstructionist curriculum. Observing the consequences of capitalism run amok, Americans became more comfortable with curricula that not only critiqued economic inequality but also encouraged students to ask critical questions about the American past. Harold Rugg wrote his popular textbook series during the Depression.

Beginning in the late-1920s, Rugg began writing and publishing social studies textbooks centered on the question of “the American problem.” The textbook series was titled Man and His Changing Society, with individual titles like An Introduction to American Civilization, Changing Civilizations in the Modern World, and An Introduction to the Problems of American Culture. The textbooks focused on the economic and demographic growth of modern cultures and the development of decision-making skills. Rugg wanted junior high school texts to provide a comprehensive introduction to the modern world so that students could face the chief concerns that they would face as adults. Rugg’s textbooks opened with a dramatic historic episode, focused on key concepts, told dramatic stories, and included stimulating photos and cartoons. In addition, the textbooks raised serious questions about the nation’s social and economic institutions. This included critiques of unequal distribution of wealth and civil rights for African Americans..

The Great Depression’s horrible poverty helped Rugg’s social reconstructionist ideas gain prominence. Social reconstructionist curricula focused on the economic challenges facing the United States and the ways that schools could improve society. In 1933’s The Great Technology, Rugg called for “social engineering in the form of technological experts who would design and operate the economy in the public interest.” For Rugg, the challenge was to “design and operate a system of production and distribution which will produce the maximum amount of goods needed by the people and will distribute them in such a way that each person will be given at least the highest minimum standard of living possible.” George Counts, one of Rugg’s colleagues at Teachers College, expressed a similar view of education in 1932’s Dare the School Build a New Social Order? Counts pushed for a system of public education where teachers and students would critically examine America’s social institutions and chart solutions to the challenges that lay ahead.

As Rugg’s popular textbooks gained widespread use, a small group of influential conservatives challenged his social reconstructionist agenda. The bulk of criticism came from business journalists, retired military, and professional historians. Most of the criticism took place in New York and New Jersey. The fervor over Rugg’s textbook series led some school boards to censor the books or declare that they contained nothing subversive. As a result, Rugg’s accusers, many of whom Rugg debated face-to-face in public forums, were relatively unsuccessful at removing the textbooks from classrooms during the 1930s.

The 1940s were a different story, though. The Second World War brought a dramatic change not only in the minds of the public but also in what people wanted from history education. Instead of reading about how to improve American society, many people wanted their children to hear about what was right in American institutions. The United States was fighting a vicious two-front war against the Japanese Empire in the Pacific and Nazi Germany and its allies in Europe and North Africa. In the battle for hearts and minds against fascism, schools told students that it was honorable to give one’s life for American democracy. Social reconstructionist education was overtaken by patriotic education.

In order for a patriotic education to take root, Americans needed to know more U.S. History than what schools were teaching. In 1942, Allan Nevins, a professor of American history at Columbia University, wrote an article titled “American History for Americans” for the New York Times Magazine. Nevins believed that “young people are all too ignorant of American history.” He speculated that “the majority of American children never receive the equivalent of a full year’s careful work in our national history.” Nevins blamed schools and colleges. “Our education requirements in American history and government have been and are deplorably haphazard, chaotic, and ineffective,” he wrote. In 1943, the New York Times conducted a survey of 7,000 college freshmen at 36 colleges that seemed to confirm Nevins’ opinion. The findings found a striking “ignorance of even the most elementary aspects of United States history.”

After the Second World War, social reconstructionist educators faced more powerful opponents: anti-communist crusaders. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) rounded up U.S. citizens suspected of communist ties. Professional educators feared for their jobs if they taught anything remotely critical in their American History courses. The risk of being labeled a communist was a serious threat. A few additional changes effectively killed the social reconstructionist movement. Under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance. This change reinforced the emerging understanding that the United States was not only a Christian nation but that it inhabited God’s chosen people. It was thus necessary to teach children that their Christianity was an asset against the godless communists in the Soviet Union, China, and elsewhere in the world. Then the U.S. economy rebounded after WWII. Consumer goods were more readily available. The average white citizen benefited from much better living conditions. Capitalism, it seemed, was proving that it offered many advantages over communism.

The early Cold War provided a climate for history education that has influenced the recent Texas history textbook controversy. U.S. citizens are still debating the role of Christianity in the nation’s history and whether elementary and high school students should learn the unpleasant truths that have been a part of America’s history. These different visions for history education will continue to divide politicians, professors of history, teachers, parents, teacher educators, students, and other concerned citizens in the years to come.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.