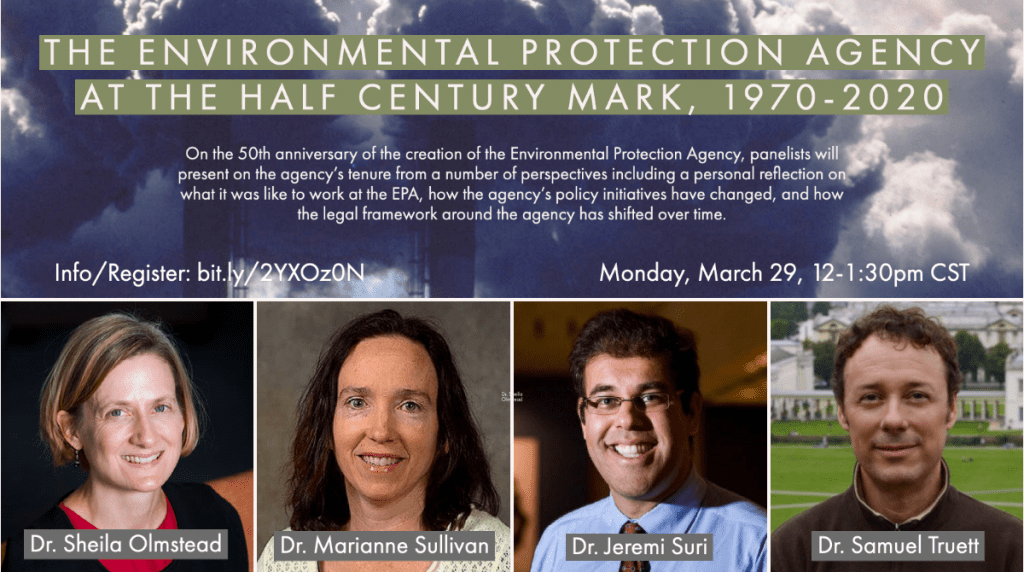

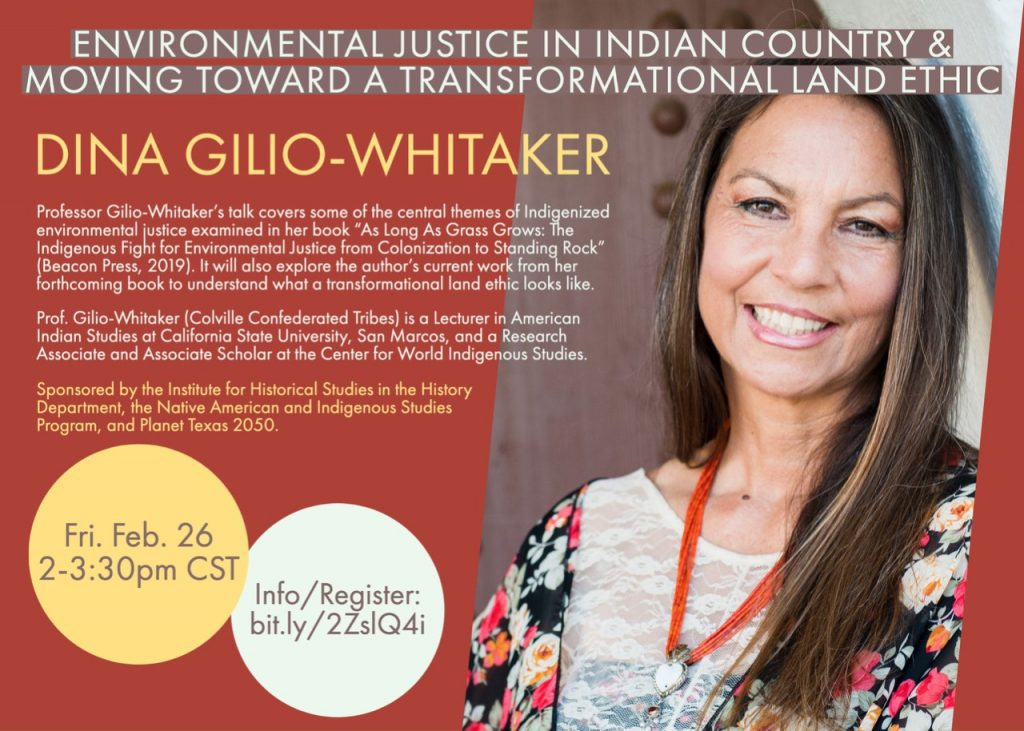

Institute for Historical Studies, Monday March 29, 2021

On the 50th anniversary of the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, panelists will present on the agency’s tenure from a number of perspectives including a personal reflection on what it was like to work at the EPA, how the agency’s policy initiatives have changed, and how the legal framework around the agency has shifted over time.

Featured Speakers:

Sheila Olmstead

Professor of Public Affairs

University of Texas at Austin

https://lbj.utexas.edu/olmstead-sheila

Marianne Sullivan

Professor of Public Health, and Director, Global Public Health Honors Track

William Paterson University of New Jersey

https://wpconnect.wpunj.edu/directories/faculty/default.cfm?user=sullivanm19

Jeremi Suri

Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs, and Professor of History

University of Texas at Austin

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/js33338

Samuel Truett

Associate Professor of History

Director, Center for the Southwest

University of New Mexico

https://history.unm.edu/people/faculty/profile/samuel-truett.html

This talk is part of the Institute’s theme in 2020-2021 on “Climate in Context: Historical Precedents and the Unprecedented.”

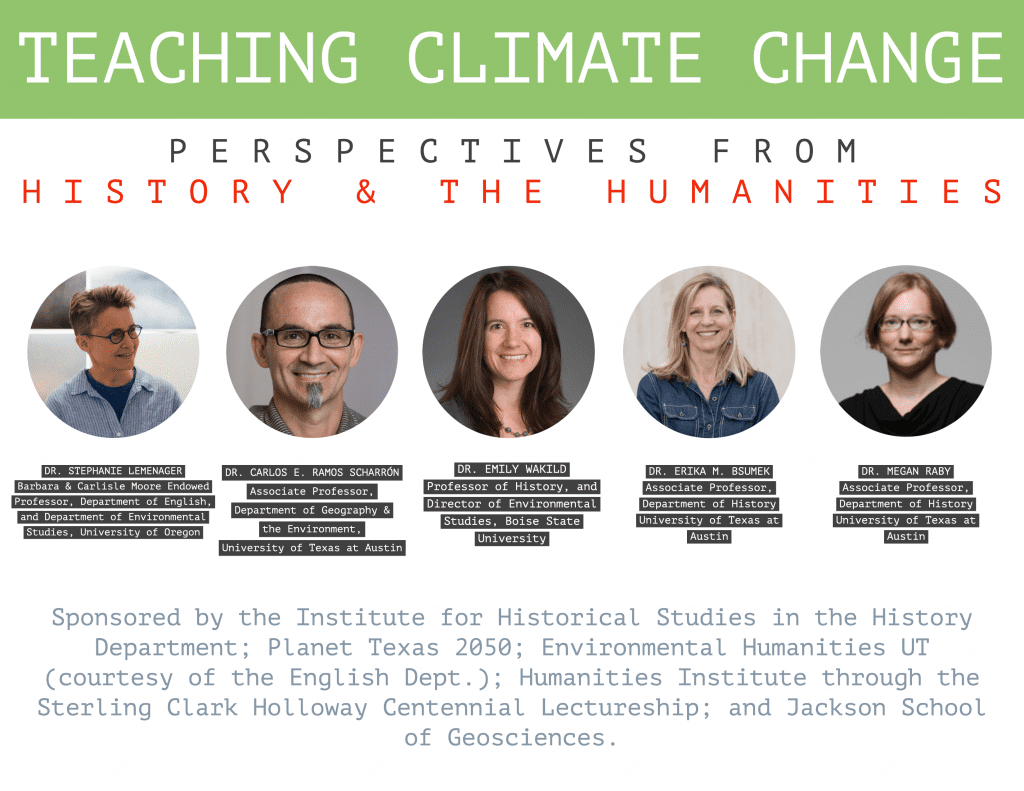

Sponsored by: Institute for Historical Studies in the Department of History, and Planet Texas 2050

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.