The title of this book is plural for a reason. John Soluri ranges across borders in both directions to show the links between the culture of banana consumption in the United States and its effects on workers and the environment in Honduras, as well as how the realities of banana plantations shaped the banana culture in the United States. While many authors focus on the fruteras, banana companies such as United Fruit (present day Chiquita), Soluri shows how the companies, the workers, and even banana pathogens were all actors in shaping what he calls “banana cultures,” even if they are not equal in their power to do so.

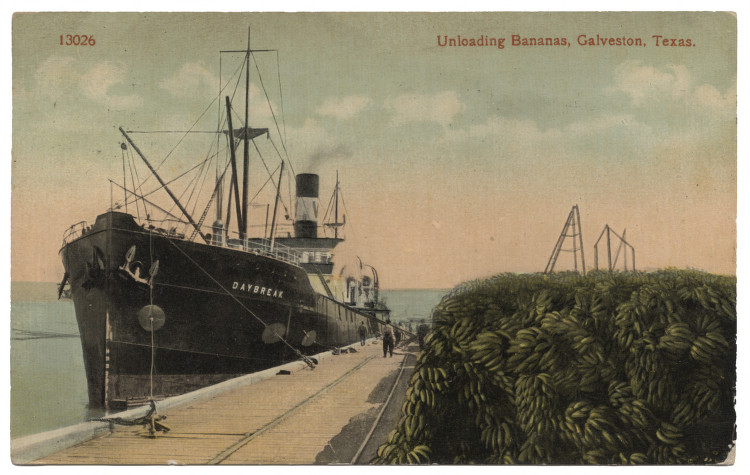

The early banana trade came at a time when few North Americans had ever tasted a banana; the now familiar fruit was still strange and exotic. Some early twentieth-century cookbooks even warned mothers to cook bananas before serving them to children. Soluri traces the first transactions, when islanders sold bananas at dockside to passing schooner captains, who soon figured they could make a handsome profit importing the exotic fruit. Residents of the Bay Islands on the North coast of Honduras soon started farms, but within a decade, their production declined heavily as soils weakened. This would be just the first of many problems encountered in the cultivation of bananas as a monoculture, problems that would shape the history of its cultivation as various pathogens affected large plantations in the prominent Honduran north coast, where a good percentage of United States supply was grown. As the fruteras started planting on the north coast, the political interference that other historians have so well documented soon followed, such as the planters’ involvement in a coup d’etat to secure government concessions. Soluri, however, argues that political machinations are not the greatest concern in this history, since the fruit companies would soon find that dealing with workers, independent growers, and banana pathogens would prove much harder than bribing or pressuring politicians.

With the banana monoculture spreading along the Honduran north coast, the importance of workers and pathogens as two principal actors in this book comes to light. The advent of the Panama disease, which was not a problem in dispersed small scale farms, but now spread like wildfire in massive plantations, brought about monumental changes. Soluri very meticulously documents the scientific struggle to fight the disease and its correlation to market pressures in the North American market. Because it was easy for the fruteras to get land concessions from the Honduran government, and because they failed to solve the problem through the creation of hybrids, the companies set about shifting plantation grounds to escape the disease, a land grab with great impact on the north coast and its availability of fertile soils.

Soluri narrates the struggles of workers and independent banana growers based on a number of sources, including censuses, local papers, letters between organizations and officials, worker organizations, literature and more. He dispels the notion that leviathan fruit companies completely pushed out small growers, and rather documents how, in many cases, they were able to use their strength to gain bargaining power. Later on after the 1950s, company employees did the same thing.

Growers and workers used nationalist rhetoric, proposing colonization projects to plant in Indian lands, and they used the fruit companies’ discourse of bringing modernity to the indomitable and disease ridden jungles. They requested the same kind of land concessions the fruteras obtained from the government, but did so as “true sons” of the Honduran nation. Growers and employees, Soluri demonstrates, had more power to shape the banana monoculture than previously thought, although expensive treatments against banana pathogens favored the large fruit companies whose massive operations could better absorb the new costs.

Soluri’s narrative, well-written and informed by popular culture and oral histories, is also very engaging for readers of any background. By providing a comparative perspective in his last chapter, he also highlights the implications of his approach and points to some other commodities, such as coffee and sugar, that could benefit from his approach.

Considering that literature on Honduras is so scant, Soluri could have written an exciting and easily publishable narrative of the fruteras’ involvement and strong-arming of the Honduran government. Instead, Soluri breaks the mold with Banana Cultures and shows us that borders, national or disciplinary, should have little meaning for a historian if his subject of study is constantly crossing them.

Further reading:

Author Dan Koepel’s Banana Blog.

An excerpt from Banana Cultures, courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.