We need new men, normal children, strong workers, and loyal soldiers . . . , and much of this can be achieved by cultivating Mexican women, showing them horizons that they have not contemplated.

-Dr. Carmen Alarcón, 1942[1]

In 1922, socialist feminists such as Elvia Carrillo Puerto and Esperanza Velázquez Bringas organized eugenic campaigns promoting anti-natalism in Yucatán, México. These campaigns encouraged poor women to stop reproducing in an effort to “make a selection of individuals for the good of the race.” [2] How can we explain the relationship between eugenics and political positions such as feminism and socialism in post-revolutionary Mexico? To modern eyes such connections seem strange or counterintuitive. While contemporary feminism demands access to abortion and contraceptives, it does so in the name autonomy and voluntary motherhood. To the contrary, eugenics proposes the regulation of reproductive functions by the State and for its benefit. The anti-natalist discourses enunciated by a variety of socialist feminists did not revolve around increasing individual rights for women but around their role in the reconstruction of the nation.

In the wake of the Mexican Revolution at the beginning of the twentieth century, several political imperatives—including anticlericalism, state-building, science, and unifying myths around race—created a fertile ground for eugenics to flourish in the ideals promoted by Mexican intellectual and political elites, as well as in the minds of socialists and feminists. Perhaps not surprisingly class played a significant role here. Among feminists, social class determined who participated in the implementation of eugenic programs. Upper middle-class people made the speeches and executed policy. As Buck (2001) states, lower-class women were the primary targets. For example, when Esperanza Velázquez Bringas addressed a meeting of the Rita Cetina Gutiérrez Feminist League (LRCG), she declared that the number of children poor women had should be restricted so, she claimed, “the product is good.”

Although its history remains underexplored in the public sphere, the relationship between eugenic and feminist discourses in Mexico during the early 20th century has been the subject of an important and growing body of international scholarship. Researchers such as Zoraya Melchor (2018) and Nancy Stepan (1991) have explored the relationship between gender, eugenics, public health, and state building in Mexico and Latin America. Cecilia Alfaro (2012) and Alexandra Stern (2002) delve into childcare and concerted motherhood as a means to cultivate a “fitter” population. Gabriela Cano (1990), Verónica Oikón (2017), and Beatriz Urías (2003) describe the contentious politics of abortion in Mexico in the 20s and 30s, while Sanchez-Rivera (2022) and Stern (2011) specifically explore sterilization as a product of eugenics. Sarah Buck’s (2001) article about the reactionary origins of Mother’s Day provided particularly useful examples of the eugenic actions I will describe below.

The Emergence of Eugenics in Mexico

Eugenics is a medical-hygienic set of beliefs and practices that reached its peak in the first half of the 20th century in the United States, Europe, and parts of Latin America, including Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. It calls for a “selective management of human reproduction” to “maintain or improve the genetic potential of the species.” Eugenics sought to prevent “abnormal” and “unfit” people from reproducing, an intervention it justified through pseudoscientific arguments related to disciplines such as demography, medicine, psychology, and sociology. Eugenicists considered conditions such as alcoholism, mental health issues, STIs, sexual “deviations,” and drug addictions to be hereditary. To stop these conditions from spreading, they promoted anti-natalism for those who had them. According to the doctors of the time, the inheritance of these traits was related to the perpetuation of “primitive” racial types and disadvantaged social classes.[3]

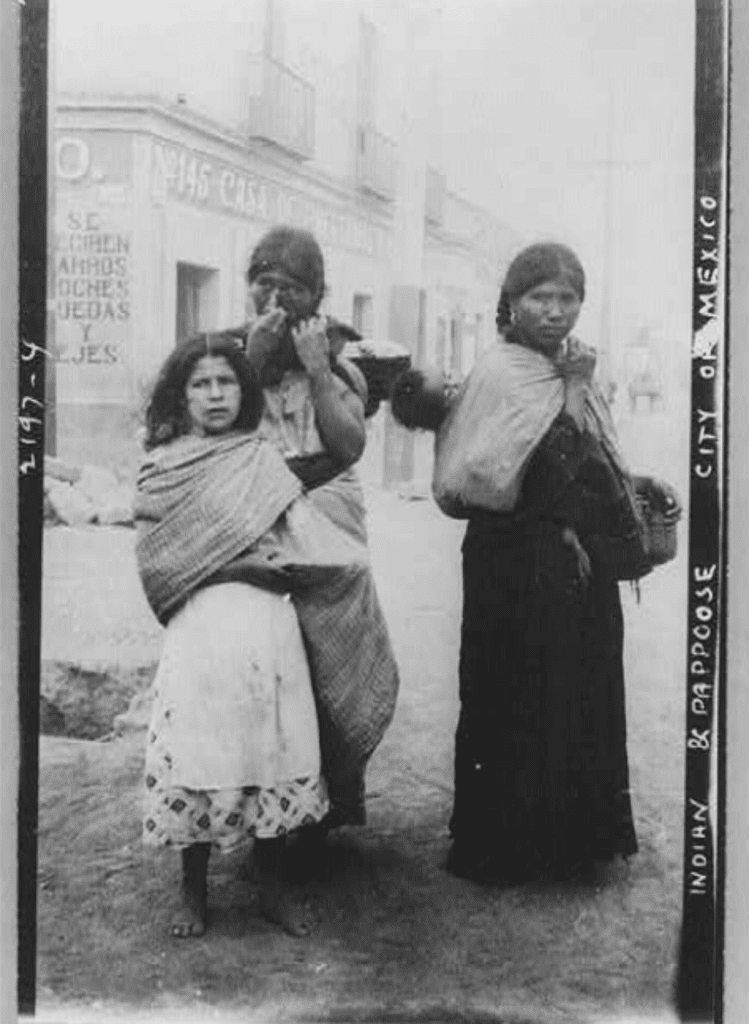

Mexican eugenics were echoed in the post-revolutionary ideals of state-building, unification, and fervent anticlericalism. After the Revolution, Mexican political and intellectual elites saw science as their closest ally in their quest to “modernize,” “civilize,” and reconstruct Mexico for the betterment of the nation and in efforts to keep up with the West.[4] In the post-revolutionary years, unifying racial myths were popularized to achieve national integration, such as José Vasconcelos’ celebration of mestizaje (indigenous and Spanish mixedness)and Manuel Gamio’s indigenism.[5] While Indigenous people were discursively recognized, they continued to be relegated and stigmatized, to the point of relating them, along with poverty, to social degeneration.

Anticlericalism was also central to post-revolutionary ideals, which sought to use science on behalf of the State to intervene in the hitherto sacred laws of nature and finally be able to “improve the race.” While the Church urged people to accept their God-given social roles, socialism and feminism struggled to reject such resignation and claim new spaces that challenged traditional gender and class positions. Homogenizing eugenicist discourses also resonated with socialists for their efforts to eliminate social classes by purging the unfit population and keeping those individuals who could successfully integrate into a more egalitarian and “superior” society.

The Revolution also created conditions that focused the attention of political elites on public health. Armed conflict, epidemics, and increasing migration to the United States caused the national population to decrease by 5%; the infant mortality rate exceeded 20%. To deal with the above, Article 73 of Mexico’s 1917 constitution instituted a “health dictatorship.”[6] In 1929, the staff of the Child Hygiene Services founded the Mexican Society of Childcare, and two years later, several of its members founded the Mexican Society of Eugenics for the Improvement of Race(SEM). The society included doctors, psychologists, and lawyers. There were five women among its 20 founding members.[7]

Eugenic Policies Implemented

In 1928, Mexico made prenuptial exams mandatory by law, and marital licenses were prohibited for individuals with chronic and contagious diseases, with health conditions that could be genetically transmitted, or with “vices” that would supposedly endanger their offspring.[8] In the 1930s, different state health and education departments began to apply IQ tests and anthropometric studies to boys and girls, mostly among poor and indigenous people.[9] Under the slogan “Temperance: for the country and the race,” the Department of Public Health launched an anti-alcoholism campaign in 1936 and agreed to form a women’s league that would combat alcoholism at home and promote the prohibition and the regulation of alcohol. The campaign was also launched in schools, employing slogans such as “alcoholic parents give rise to degenerate children” and “out of every hundred crazy people, ninety are children of alcoholics.”[10]

In 1930, the Department of Public Health decreed that “every woman residing in Mexican territory had the duty to contribute, within the law and per the principles of eugenics, to the good and health of the country’s population.”[11] The national newspaper El Universal called for mothers to send portraits that evidenced the good condition of their children to put them in the “Gallery of Robust Children.”[12] In this sense, the bodies and practices of women became an arena for state intervention, especially concerning maternalistic eugenics linked to childcare and natalism. Mothers were in charge—within the domestic sphere—of helping to reform the population’s alleged bad habits and degenerate practices.

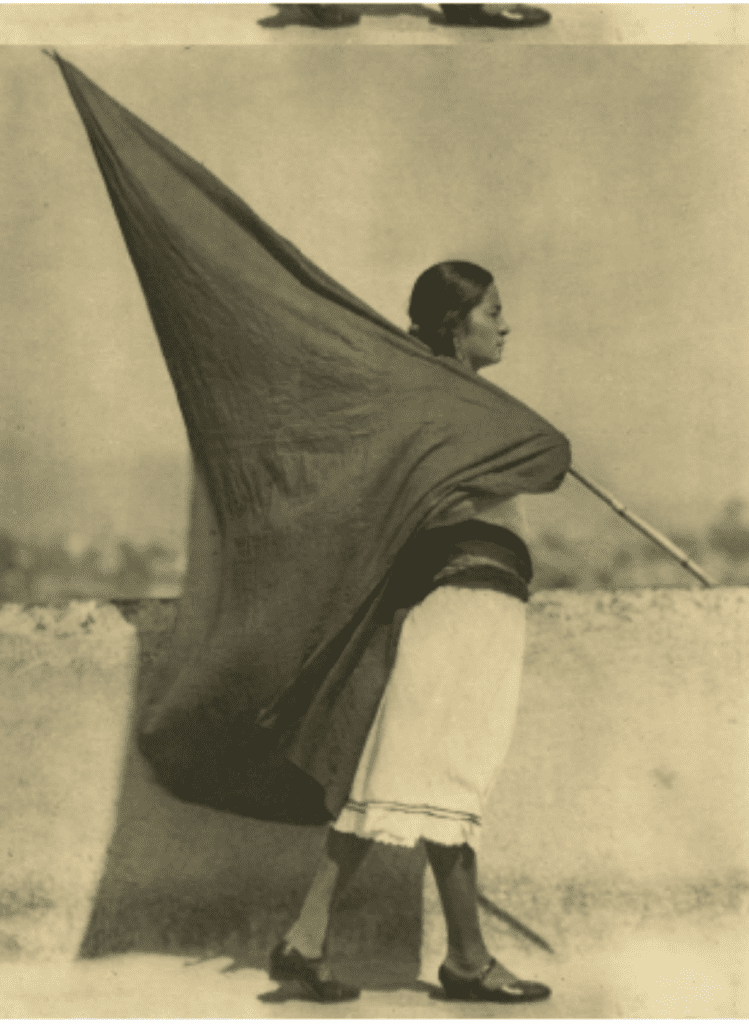

Esperanza Velázquez Bringas, a journalist, pedagogue, and feminist from Veracruz, envisioned different measures for different social classes. Her articles in El Universal were aimed at middle-class women and revolved around childcare, with advice on how to better care for children. On the other hand, the measures she proposed for lower-class women were related to the restriction of their reproduction. As Buck (2001) recounts, Velázquez organized birth control campaigns in Yucatán in collaboration with Felipe Carrillo Puerto and the Rita Cetina Gutiérrez Feminist League. In 1922, Carrillo Puerto authorized the distribution of Margaret Sanger’s pamphlet “Birth Regulation or the Compass of the Home: Safe and Scientific Means to Avoid Conception” in the Civil Registry and Yucatecan socialist newspapers. Sanger was a U. S. pioneer in the promotion of birth control and the founder of the first clinic for this purpose, which later became Planned Parenthood. Her pamphlet proposed that regulating births was the responsibility of the State but that it was also necessary to make knowledge available to prevent newborns from “degenerate” or sick parents.

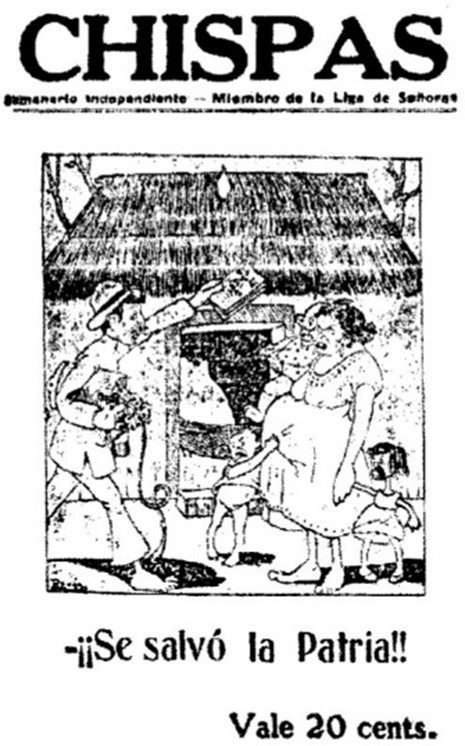

Historian Sarah Buck has called attention to a 1922 cartoon (see below) that reveals exactly who the campaign and pamphlets targeted.[13] The cartoon shows a man handing out the Sanger pamphlet to a woman in rustic, rural, lower-class dwellings. She has many children, who are depicted as disheveled and bad-tempered. On the other hand, the man carries a vaginal douche. The image satirizes the gendered efforts to “save” the country through hygiene and birth control campaigns.

Despite the classist overtones of the campaigns, they incorporated a discourse of liberation from the burden that perpetual motherhood represented. They demanded that women “stop being incubators and be women who have a child whenever they want, but only when they have the economic conditions to support and educate their offspring.”[14] News of protests led by Yucatecan mothers who opposed the distribution of the pamphlet were published in the newspaper Excelsior. Later, on April 13th, 1922, the newspaper launched the proposal to consecrate May 10 as a day to honor mothers since, in Yucatan, “a suicidal and criminal campaign against motherhood has been started.”[15]

One year after the first Mother’s Day, anti-natalism resurfaced on the feminist agenda at the Pan-American Conference of Women, where Mireya Rosado and Elizabeth McManus from the United States suggested that the State carry out campaigns to convince proletarian families to limit their reproduction. The profile of the congress attendees reveals that they were mostly women from Mexico City or large cities, mostly professors and a significant minority of doctors. These were educated, urban, middle- or upper-middle-class women, and there was no representation of those whose birth rate they sought to control.

A decade later, similar ideas took root in Veracruz, where the only eugenic sterilization law in Latin America was passed in December 1932.[16] But in practice, the law probably resulted in few or no surgeries. Contrary to the way events unfolded in countries such as the United States, Sweden, and Germany, it is unlikely that sterilizations were carried out continuously, mainly due to a lack of infrastructure and agreement about the specific places where they were allowed. [17]

Eugenics and Abortion

Abortion was a contentious issue between feminist and non-feminist eugenicists. For the latter, it was unacceptable because it contradicted “the fundamental function of the female, which is to procreate,” in addition to the fact that in abortion it is unknown if the “product” (e. g., the child) “was good or bad.”[18] For this reason, non-feminist eugenicists focused on sexual education and restrictive policies meant to “improve” national progeny. Some feminists, however, advocated for abortion on a socioeconomic basis.

In 1936, Dr. Rodríguez Cabo presented the paper “Abortion for social and economic reasons,” where she proposed the abolition of abortion as a crime if related to economic and social reasons and to make contraceptive methods available to poor mothers.[19] While non-feminist eugenicists solely centered on the procreating “function of the female,” Rodríguez Cabo and those who supported abortion for socioeconomic reasons challenged the natural connection between womanhood and motherhood. Even so, both stances denied women’s individual choice, favoring the control of their reproduction instead of autonomy. Rodríguez Cabo spoke in favor of birth control and abortion. Her feminism had a eugenic, maternalistic, and welfarist vision. However, she planted the seeds for actions in favor of the decriminalization of abortion. [20]

Contentious Feminism in Post-Revolutionary Mexico

The feminist eugenicist discourses around anti-natalism revolved around women’s role in rebuilding Mexico. Upper-class women played the part of a “social mother,” where they tried to help less favored women by imposing their worldview. These feminists showed sympathy for poor people but from an urban, middle-class mentality and morality. Through them, they sought to impose their conceptions of family planning and reproduction on women who did not necessarily share their ideals. Eugenicists thus “juxtaposed democratic demands for individual freedom with authoritarian prescriptions addressed to their recipients (poorer Mexican women), in an effort to make their ideals of development a reality.”[21]

Anti-natalist campaigns aimed to respond to severe cases of infant mortality and malnutrition by imposing on women not represented in the movement what others perceived as a desirable way of life. These policies centered on a state-building project rather than in the advancement of women rights. These efforts paved the way for the creation of institutions that did help working-class women, such as childcare in factories, public kitchens, contraception, and the legalization of divorce. However, “they subordinated the position of women to the domestic and social sphere [and fixed] a morality that circumscribed female sexuality to marriage and procreation.”[22]

The relationship between eugenics and post-revolutionary feminism is complex and paradoxical. On the one hand, in addition to being profoundly discriminatory on a race and class basis, eugenics perpetuated the reduction of women’s social functions to their reproductive capabilities and the domestic sphere. On the other, it fostered dialogue on fundamental issues on the feminist agenda, such as abortion, contraceptive methods, and public policies regarding maternal health and childcare. It allowed, in a secondary and circumscribed way, the participation of professional women, mainly doctors and professors, in public discussions and government positions relevant to state building. Feminist and socialist militants participated in these discussions, concerned, if perhaps condescendingly and from their class position, about the precarious living conditions of women and proletarians and about influencing the spaces where the material and symbolic reconstruction of a troubled nation was being configured.

Recognizing this complicated history in the face of contentious reproductive rights reminds us to be vigilant of class consciousness and intersectionality when defending bodily autonomy and, as Gloria Steinem states, “question any tactics that fail to embody the ends we hope to achieve.”[23]

Daniela Sánchez is a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology at The University of Texas at Austin. She is a Fulbright-García Robles Scholar and a ConTex Doctoral Fellow. Her research interests lie at the intersection of gender, inequality, reproductive labor, and wealth. Before joining the department, Daniela was a consultant for UN Women-Mexico. She holds a BA in Sociology from UNAM, a BA in Communications from ITESM, and a MA in Gender Studies from El Colegio de Mexico.

Bibliography

Alfaro, Cecilia. “Puericultura, higiene y control natal. La visión de Esperanza Velázquez Bringas sobre el cuidado materno-infantil en México (1919-1922).” Historia Autónoma 1 (2012): 107-119.

Buck, Sarah. “El control de la natalidad y el día de la madre: Política feminista y reaccionaria en México, 1922-1923.” Signos históricos 5 (2001): 9-53.

Cano, Gabriela. “Una perspectiva del aborto en los años treinta: la propuesta marxista.” Debate Feminista 2 (1990): 362-372.

Melchor, Zoraya. “Eugenesia y salud pública en México y Jalisco posrevolucionarios.” Letras Históricas 18 (2018): 93-115.

Oikón, Verónica. “Un atisbo al pensamiento y acción feministas de la doctora Mathilde Rodríguez Cabo.” Relaciones Estudios de Historia y Sociedad 149 (2017): 101-135.

Sánchez Rivera, R. “From Preventive Eugenics to Slippery Eugenics: Population Control and Contemporary Sterilisations Targeted to Indigenous Peoples in Mexico.” Sociology of Health & Illness, accessed October 5, 2022.

Steinem, Gloria, “Margaret Sanger,” Time, April 13, 1998.

Stepan, Nancy, The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America. New York: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Stern, Alexandra. “’The Hour of Eugenics’ in Veracruz, Mexico: Radical Politics, Public Health, and Latin America’s Only Sterilization Law.” Hispanic American Historical Review 91/3 (2011): 431-443.

–. “Madres conscientes y niños normales,” in Cházaro (ed.), Medicina, Ciencia y Sociedad en México, Siglo XIX (2002) 293-336.

–. “Mestizofilia, biotipología y eugenesia en el México posrevolucionario: Hacia una historia de la ciencia y el estado, 1920-1960.” Relaciones: Estudios de Historia y Sociedad 21/81 (2000): 59-91.

Urías, Beatriz. “Degeneracionismo e higiene mental en el México posrevolucionario (1920-1940).” Frenia: Revista de Historia de la Psiquiatría 4/2 (2004): 37-67.

–. “Eugenesia y aborto en México (1920-1940).” Debate Feminista 27 (2003): 305-323.

[1] Carmen Alarcón, “¿Qué ha hecho usted por la mujer?”, Asistencia: Órgano de la Secretaría de la Asistencia Pública, II/5 (1942), 13.

[2] Sarah Buck, “El control de la natalidad y el día de la madre: Política feminista y reaccionaria en México, 1922-1923,” Signos históricos 5 (2001), 11.

[3] Beatriz Urías, “Degeneracionismo e higiene mental en el México posrevolucionario (1920-1940),” Frenia: Revista de Historia de la Psiquiatría 4/2 (2004), 305, 307.

[4] R. Sánchez Rivera, “From Preventive Eugenics to Slippery Eugenics: Population Control and Contemporary Sterilisations Targeted to Indigenous Peoples in Mexico,” Sociology of Health & Illness, accessed October 5, 2022, 2.

[5] Urías, “Degeneracionismo e higiene mental,” 39.

[6] ibid., 58.

[7] Alexandra Stern, “Madres conscientes y niños normales,” in Cházaro (ed.), Medicina, Ciencia y Sociedad en México, Siglo XIX (2002), 302.

[8] Nancy Stepan, The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America (New York: Cornell University Press, 1991), 123.

[9] Robleda, “Biological characteristics of proletarian schoolchildren,” cited in Nancy Stern, “Mestizofilia, biotipología y eugenesia en el México posrevolucionario: Hacia una historia de la ciencia y el estado, 1920-1960,” Relaciones: Estudios de Historia y Sociedad 21/81 (2000), 86-87.

[10] Archivo General de la Nación, Secretary of Public Education, Memoirs, 1936, 35, 37.

[11] Zoraya Melchor, “Eugenesia y salud pública en México y Jalisco posrevolucionarios,” Letras Históricas 18 (2018), 100.

[12] “Gallery of robust children,” El Universal, January 26, 1919, front page, quoted in Cecilia Alfaro, “Puericultura, higiene y control natal. La visión de Esperanza Velázquez Bringas sobre el cuidado materno-infantil en México (1919-1922),” Historia Autónoma 1 (2012), 109.

[13] Buck, “El control de la natalidad,” 18.

[14] El Popular, March 3rd, 1911, 3; and March 10th, 1922; both cited in Buck, “El control de la natalidad,” 18.

[15] Excelsior, April 13th, 1922, 10, quoted in Buck, “El control de la natalidad,” 3-4.

[16] “Vera Cruz to Adopt Birth Control Today,” New York Times, November 1st, 1932, 5.

[17] Alexandra Stern, “’The Hour of Eugenics’ in Veracruz, Mexico: Radical Politics, Public Health, and Latin America’s Only Sterilization Law.” Hispanic American Historical Review 91/3 (2011), 432.

[18] Hemeroteca Nacional Digital de México, Escontria, “Eugenics and birth control,” Gaceta Médica de México, p. 417

[19] Gabriela Cano, “Una perspectiva del aborto en los años treinta: la propuesta marxista,” Debate Feminista 2 (1990), 372.

[20] Verónica Oikón, “Un atisbo al pensamiento y acción feministas de la doctora Mathilde Rodríguez Cabo,” Relaciones Estudios de Historia y Sociedad 149 (2017),131.

[21] Buck, “El control de la natalidad,” 13.

[22] Alfaro, “Puericultura, higiene y control natal,” 118.

[23] Gloria Steinem, “Margaret Sanger,” Time, April 13, 1998.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.