In the fall of 1913, the Second American Catholic Missionary Congress took place in Boston, Massachusetts. Catholic priests, bishops, and laypeople from across the country met for three days to discuss Catholic home missions—that is, missionary work within the United States.

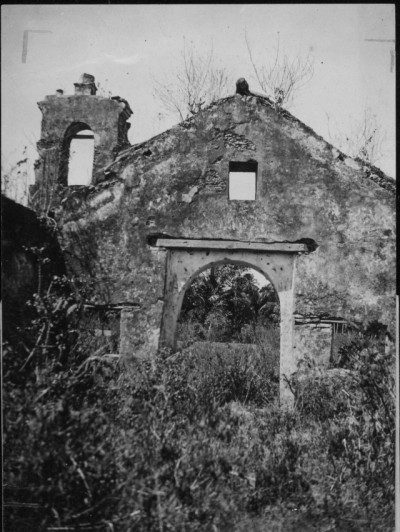

Archbishop John Baptist Pitival of Santa Fe, New Mexico represented the leadership of what he referred to as the “wild and wooly west.” In a speech repeatedly interrupted by bursts of applause, Pitival compared the ornate cathedrals he had seen in Boston with the sacred buildings that surrounded him in the Southwest. “It is the picture of another glorious edifice, hoary with age, cemented with the blood of many martyrs, with the sweat of countless apostolic men—the picture of the older Church in our great country, but now crumbling into ruin, disintegrating pillar by pillar—nay, stone by stone, moreover exposed to the fierce attacks of a relentless foe. It is our Catholic Church in the Southwest.” Echoing Lamentations 4:4, he continued, “‘Behold, our children are crying for the bread of God’s Word and there are none to break it to them.’ Behold, we are being dispossessed of our lands; we are a doomed and vanishing race.” Pitival feared that the Church in the Southwest was vanishing due to the rapid encroachment of Protestant proselytizers attempting to convert Mexican American Catholics. Pitival was not Mexican, or even American, but seemingly represented Mexicans in the southwest by claiming that we were being dispossessed of our land. “The white man,” he continued, referring to Eastern Protestants, “is enjoying the fruit of the land that we inherited from our fathers.” With this, the archbishop subtly transitioned from the Mexican “we” to the Catholic “we,” thereby reclaiming the American Southwest for American Catholics. “After being robbed of our earthly heritage, are we to be deprived of our heavenly birthright also?”

Pitival began by invoking the familiar image of the West in the mind of the Northeasterner but ended by reminding his audience that this territory, in fact, had a Catholic past. His embrace of the Spanish Catholic past was an important part of building an American Catholic missionary ethos in the early twentieth century.

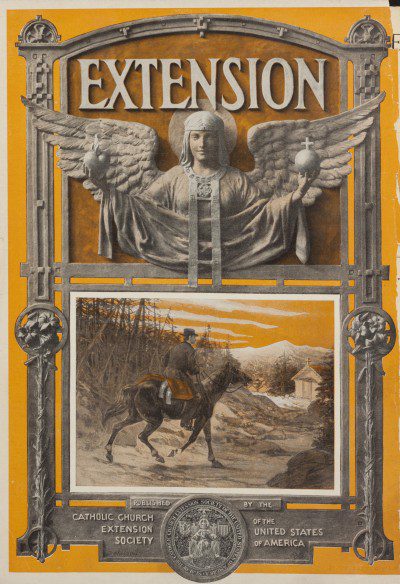

Catholic borderlands were the areas like Pitival’s New Mexico where the Spanish Catholic past and the U.S. Catholic present were layered to create a uniquely American Catholic phenomenon. Father Francis Kelley, founding president of the Catholic Church Extension Society, was the main architect of this American Catholic spirit. He built on the legacy of the Spanish Catholic friars who founded the missions dotting the southwest centuries earlier, and risked life and limb tending to the souls of the indigenous not only on the North American continent, but in Puerto Rico and the Philippines as well. Kelley and the Extension Society provided financial support to Catholic missionaries from all over the world – Pitival was French – to carry out the American civilizing mission at the rugged edges of the American national landscape.

This activity reaffirmed what they saw as the inherent Catholicity of theses places. At the same time, their projects conferred “Americanness” to those funding them: urban, Euro-American Catholics. In the early twentieth century, many Catholics were still treated as foreigners or as questionably American due to their presumed loyalty to the Pope before the President. Their participation in these mission projects, however, allowed American Catholics to assert their claim to Americanness by taming the West and far-off U.S. territories in the name of Catholicism and American empire.

This vision of the borderlands recognizes that it is more than a single geographic space along the U.S.-Mexico border. Rather, the borderlands encompasses a wider swath of American interaction with Spanish peoples in asserting influence and control. The United States coveted Spanish and former-Spanish territories in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The link between American expansion and Protestantization guaranteed that religious tensions would ensue as American government and Protestant religious bodies established themselves in these predominantly Catholic spaces. Francis Kelley orchestrated an American Catholic intervention in Mexico that addressed these issues: protect Mexican Catholics from the Protestant poachers moving in to corrupt vulnerable Catholic souls and restore the natural order – Catholicism – to this space on the fringe of the American empire.

Father Kelley’s project gave Catholics a complicated role in American empire in the early twentieth century. Wielding Mexico’s religious crisis as a sword, American Catholics simultaneously benefited from and sought to undermine various aspects of American expansion. Catholics were pleased with formal and informal annexation of former Spanish territories through the Spanish-American War and interventions in Mexico. However, they resisted cultural aspects of American empire, in particular the spread of Protestantism, and they fought to sustain Catholic souls in the face of Americanization and proselytizing efforts.

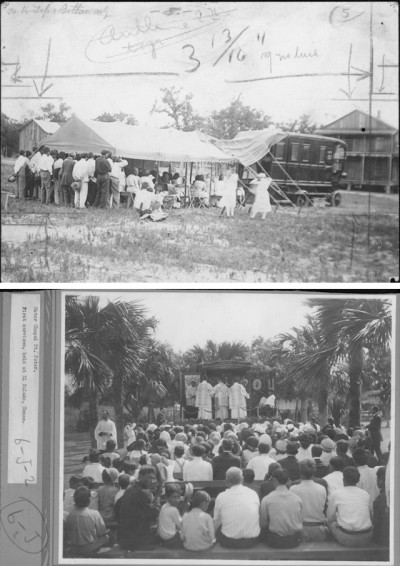

Photos like this one, in Aguado, Puerto Rico, were shown in Extension Magazine to remind readers – Catholics all over the United States — that if they did not attend to Catholics in remote areas of the American empire, their churches might end up like the earliest Spanish Catholic Churches in the New World – abandoned and crumbling, just as Archbishop Pitival had described. Kelley used Extension Magazine to urge relatively well-off Catholics, mostly in the Northeast and Midwest, to support their less fortunate brethren in the South, West, and throughout the American empire.

Anne M. Martínez, Catholic Borderlands: Mapping Catholicism onto American Empire, 1905-1935.

Anne Martínez taught US Borderlands and Mexican-American history at the University of Texas at Austin. She is now in the Department of American Studies at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

For more reading on the Catholic borderlands, look here on our books page.