This article first appeared on Imperial and Global Forum, University of Exeter, UK (July 6, 2015)

In the wake of the shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, the United States has undergone a deep soul searching. Images of the confessed shooter posing with the Confederate Battle Flag have launched a long-overdue national debate about the meaning of Confederate imagery. But they have quickly overshadowed the shooter’s use of two other symbols: the defunct standards of Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and apartheid South Africa.

Though not nearly as ubiquitous as the “stars and bars,” these totems symbolize an international segregationist philosophy of white superiority. While historians have rightly focused on the transnational dimensions of decolonization and the civil rights movement, there was also a smaller, if no less global, reaction against these trends. Both South Africa and Rhodesia actively cultivated alliances with reactionary white populations abroad, building support in the United States, particularly in the area of the old Confederacy. The Charleston shooting therefore serves as a violent reminder that American racism today is not only a regional issue – it has also been shaped by a decades-long global opposition to human and civil rights.

This particular transnational solidarity of whiteness emerged as a response to the interconnected struggles for civil rights and self-determination during the Cold War. The ideological conflict encouraged Western countries to realize their rhetorical commitments to democracy and freedom, creating an environment conducive to both decolonization and a reevaluation of racially defined inequalities such as American segregation.

Historians have shown that these international and domestic trends complemented each other, drawing inspiration across borders and informing a general movement toward a new rights-based international system.[1] The reevaluation of race relations inherent in these movements directly challenged imperial concepts of white superiority and Europe’s self-serving “civilizing mission,” famously described by British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan in 1960 as the “wind of change.”

The normative shift away from colonialism and Euro-American dominance began the slow process of isolating segregationists in Africa and the Americas, but it also inspired them to seek transnational support through appeals to common racial and ethnic heritage. The most influential state actor on this new transnational frontier was South Africa. The nation had become the international exemplar of discriminatory official policy when it installed its apartheid system in 1948. Under attack at the United Nations and eventually ousted from the British Commonwealth, South Africa based its international propaganda campaign on two central arguments: anti-communism and negative stereotypes of black peoples. As Tim Borstelmann and Thomas Noer have argued, South Africa claimed to be a strategic bulwark in the Cold War, protecting key minerals and European economic interests from African nationalists the regime depicted as Soviet-controlled communists.[2]

South Africans also appealed to popular assumptions about the inability of colonized peoples to govern themselves. Recasting the outdated civilizational thesis in the rhetoric of the 1960s, the apartheid government argued that it strove to achieve “separate development,” helping to modernize its internal populations at different rates and in ways acceptable to Euro-American interests.[3] South Africans contended that it was white governance that allowed the country to build its modern economy and Westernized high-rise cities, minimizing the ways settler colonialism had depended on the conscious exploitation of black Africans. South Africa’s success in becoming what a 1966 Fortune article called “the only real industrial complex south of Milan” was enough to convince many business-minded Americans to overlook the country’s deep structural inequality.[4] This diplomatic propaganda effectively quieted much Western criticism of apartheid in its first two decades.

Apartheid South Africa also appealed to baser American motivations, manipulating racial fear to curry favor with more desperate elements of American society. Officials including apartheid’s architect, Prime Minister Daniel Malan, cited Kenya’s Mau Mau Rebellion and the chaotic period succeeding the 1960 decolonization of the Congo as proof of the importance of maintaining white control.[5] Violence, the argument went, would inherently follow the end of European rule, much of it targeting whites.[6] This propaganda appealed particularly to Americans in the desegregating south and urban areas, who were anxious over how the changing complexion of their communities and governments would affect future social relations.

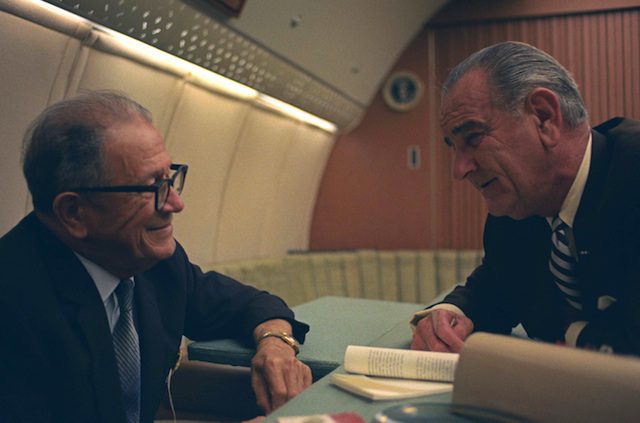

Sen. Allen Ellender (D-LA) meeting with President Lyndon Johnson. When Ellender offered to arrange for a private screening of the film documenting his 1963 African tour, the president politely declined

American segregationists gravitated to the racially motivated warnings of individuals like Malan to justify their own policies. In one memorable example from 1963, Senator Allen Ellender (D-LA) contrasted his visits to South Africa and the British colony of Southern Rhodesia with those to newly independent Africa to argue that black peoples were “incapable of leadership except through the assistance of Europeans.”[7]

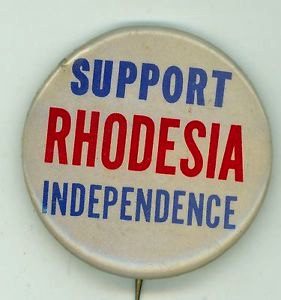

This reactionary internationalism bloomed especially after Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence in 1965. Fearing a metropolitan transfer of power that would strengthen the political power of the black majority, the white government of Southern Rhodesia broke with Britain and eventually declared itself a republic. Few nations recognized the sovereignty of the new state, which severely restricted the political and economic rights of black Africans it claimed were not yet fit to govern.

Sanctioned by the United Nations and the Anglo-American entente, Rhodesia became a symbol for disaffected Americans to argue that decolonization – and by extension civil rights – unjustly favored non-white peoples. Solidarity organizations supporting Rhodesia sprang up across the United States, with historian Gerald Horne estimating that the Friends of Rhodesian Independence alone counted 25,000 members in 122 local chapters.[8] Though barred from establishing embassies in most countries, the rogue state operated information offices in Washington and elsewhere that promoted popular solidarity and actively recruited white immigrants to bolster the minority population.

This transnational solidarity grew from a common worldview among reactionary segregationists. Southerners in particular drew on a peculiar melding of democracy and white supremacy, which institutionalized an Anglo-Saxon tradition of liberty that restricted suffrage and rights of governance to peoples of northern European descent.[9] It was this logic that they had used to justify segregation and the disenfranchisement of blacks and Hispanics. As their traditional system of white rule was undermined by civil rights, they looked abroad to South Africa and Rhodesia as the last bastion of what one conservative group called “the long-established doctrine of an informed electorate as prerequisite for self-government” that had at its center a hierarchy of race.[10]

This transnational solidarity grew from a common worldview among reactionary segregationists. Southerners in particular drew on a peculiar melding of democracy and white supremacy, which institutionalized an Anglo-Saxon tradition of liberty that restricted suffrage and rights of governance to peoples of northern European descent.[9] It was this logic that they had used to justify segregation and the disenfranchisement of blacks and Hispanics. As their traditional system of white rule was undermined by civil rights, they looked abroad to South Africa and Rhodesia as the last bastion of what one conservative group called “the long-established doctrine of an informed electorate as prerequisite for self-government” that had at its center a hierarchy of race.[10]

The dichotomy of the seemingly modern minority nations and the selectively chosen examples of chaotic independence in countries like the Congo provided evidence of the rightness of the status quo. As Thomas Noer has astutely observed, the “segregationist critique of international issues began with an attempt to use the newly independent African nations as examples of black inferiority to buttress their defense of continued white political power in the American south.”[11] As civil rights advanced, the minority governments gained sympathy as examples of a new “lost cause”.

Strikingly, South Africa and Rhodesia did not only target whites but used interlinked claims to anti-communism, economic development, and traditional race relations to justify their existence on broader conservative grounds. The two countries employed a variety of lobbyists and public relations firms to sell their segregationist societies abroad, even to the African American community.[12] In one example, South Africa covertly provided tens of thousands of dollars to the American-African Affairs Association (AAAA) under the direction of the black anti-communist Max Yergen and influential conservative commentator William Rusher, who published a series of sympathetic pamphlets on the minority governments and colonial Portugal.[13] Activities undertaken by the AAAA and similar groups lent an air of multiculturalism and multiracialism to the defense of the segregationist regimes.

Yet these wider propaganda campaigns could not disguise how the most effective support for minority governance came from disaffected whites concentrated in the southern parts of the United States. Southern congressmen took the lead in defending the minority regimes from a growing popular chorus of criticism in the 1970s and 1980s, positions that played well with many of their constituents.

A 1971 U.S. law to allow the import of Rhodesian chrome, despite a UN boycott, passed with the sponsorship of Senator Harry F. Byrd, Jr. (D-VA) alongside pressure from the Friends of Rhodesia and the segregationist Citizens’ Councils of America.[14] Other congressmen such as James Eastland (D-MS) and Jesse Helms (R-NC) had personal and professional ties to the minority regimes, and they worked actively to undermine any attempts to condemn South Africa or Rhodesia at the federal level.[15] It was only in 1986, when the American anti-apartheid movement had effectively built its own national network to counter South African propaganda, that Congress was able to pass a sanctions bill over the veto of President Ronald Reagan and place the United States firmly against minority rule.

The transformation of Rhodesia into Zimbabwe in 1980 and the collapse of apartheid in 1994 ended mainstream white transnational solidarity, but it has done little to end its afterlives in the popular American subconscious and openly at the political fringes. The stereotypes reinforced and propagated by a transnational segregationist alliance remain embedded in the United States’ national heritage.

As evidenced by events in Charleston, white supremacists maintain this anachronistic and racist view of black peoples, while media coverage of the disturbances in Baltimore and many events in Africa hint that a subliminal acceptance of these stereotypes has not fully disappeared. In much the same way that the United States is engaging with the institutional memory of the Civil War, the country would do well to recognize the lasting transnational legacies of Cold War decolonization, modernization, and official segregation.

You may also like these articles on slavery and its legacy in the US and flags, monuments, and myths about the confederate history.

[1] See in no particular order Brenda Gayle Plummer, In Search of Power: African Americans in the Era of Decolonization, 1956-1974 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013) James Meriwether, Proudly We Can Be Africans: Black Americans and Africa, 1935-1961 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001); Penny Von Eschen, Race Against Empire: Black Americans and Anti-Colonialism, 1937-1957 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997); Francis Njubi Nesbitt, Race for Sanctions: African Americans Against Apartheid, 1946-1994 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004); Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000); Thomas Borstelmann, The Cold War and the Color Line (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); Carol Anderson, Eyes Off the Prize: The United Nations and the African American Struggle for Human Rights, 1944-1955, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003) among others.

[2] Thomas Borstelmann, Apartheid’s Reluctant Uncle: The United States and Southern Africa in the Early Cold War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); Thomas J. Noer, Cold War and Black Liberation: The United States and White Rule in Africa, 1948-1968 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1985), chapters 1-2.

[3] For a discussion of how whiteness and modernization worked together to shape American attitudes toward Africa, see the work of Larry Grubbs, notably Secular Missionaries: Americans and African Development in the 1960s (University of Massachusetts Press, 2010).

[4] John Davenport, “South Africa: The Only Real Industrial Complex South of Milan,” Fortune, December 1966.

[5] See for example the interview with Daniel Malan in U.S. News and World Report, 16 April 1954, 60-66.

[6] This argument was reinforced by the Angolan rebellion of 1961, which began with a number of violent attacks on white owned farms (and even more violent responses by the Portuguese). With the aid of a public relations firm and a Lisbon-backed American organization, the government issued a number of grisly publications in English showing the mutilated bodies that not so subtly portrayed the barbarity in racial terms. See “On the Morning of March 15th,” (Boston: Portuguese-American Committee on Foreign Affairs, 1961?). Thomas Noer also touches on this theme in his article on segregationist internationalism, “Segregationists and the World: The Foreign Policy of the White Resistance,” in Brenda Gayle Plummer, ed., Window on Freedom: Race, Civil Rights, and Foreign Affairs, 1945-1988 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 141-162.

[7] Jack Anderson, “State Cables Tell Tale of Ellender,” Washington Post, 6 August 1963.

[8] Gerald Horne, From the Barrel of a Gun: The United States and the War Against Zimbabwe (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 45.

[9] Daniel Geary and Jennifer Sutton, “Resisting the Wind of Change: The Citizens’ Councils and European Decolonization,” in New Directions in Southern History: U.S. and Europe Transatlantic Relations in the Nineteenth Century (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013), 265-282. For a greater discussion of the 19th century tradition of exclusionary governance, see Reginald Horseman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981).

[10] American-African Affairs Association, Some American Comments on Southern Africa (New York: American-African Affairs Association, 196-?), III.

[11] Noer, “Segregationists and the World,” 142.

[12] Claims of communist infiltration, all-expenses paid and highly choreographed trips to the minority-ruled countries, as well as cash payments won over allies of all hues, including the conservative black columnist George Schuyler. New York Times correspondent has recently completed a book on South Africa’s international propaganda machine during the apartheid era, excerpted recently as “How apartheid sold its racism,” The Star, 25 June 2015.

[13] The AAAA used South African funds to produce the pamphlet Red China in Africa (New York: American-African Affairs Association, 1965?). Memo, J.S.F. Botha to Secretary of Foreign Affairs, 7 April 1966, Folder 1/33/3/1, South African Department of Foreign Affairs Archives (Pretoria, South Africa).

[14] In the late 1960s and 1970s, anti-apartheid activists and churches were impressed by the size and influence of the pro-Rhodesia lobby. Ken Carstens to Blake et al., “Report on visit to Congressmen in April,” 29 April 1967, Box 23, RG6, National Council of Churches Papers, Presbyterian Historical Society (Philadelphia, PA). See also Horne, chapter 4.

[15] Noer, “Segregationists and the World,” 145-146; Geary and Sutton, 272. South Africa also directly attacked congressmen who worked against their interests in the United States, likely targeting liberal internationalist and Africa subcommittee chair Senator Dick Clark (D-IA) by funneling money to his electoral opponent in 1978. For a very readable examination of this incident, see David Rogers, “A Nelson Mandela Backstory: Iowa’s Dick Clark,” Politico, 26 December 2013.