Austin is a global city, home to some of the most technologically advanced and successful corporations in the world as well as a renowned university system that provides highly trained and educated employees to those same top companies. All the while, Austin’s constant obsession with building a sustainable and environmentally friendly city contributes to the growth of a largely white upper-middle class demographic who can afford living in proximity to Austin’s finest and natural recreational spaces. A look at Austin’s past reveals a pattern of racial discrimination as the city constantly places the needs of white residents, boosters, developers, and investors above those of Black and Latino residents.

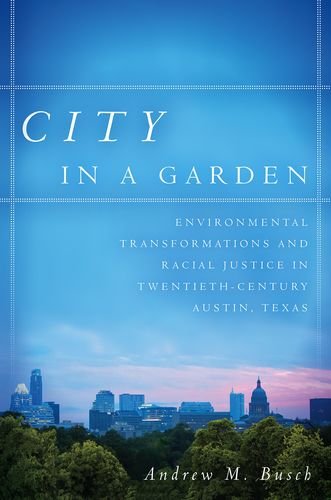

Andrew M. Busch’s new book, City in a Garden traces one hundred years of Austin’s urban, environmental, political, and social history. Busch explains that Austin’s investment in big business and innovative environmental development projects was and still is an investment in the social construction of whiteness that has paid off beautifully for upper-middle class white people. Busch argues that no matter how sustainable Austin is, or remains, there is a troubling “shadow” constantly growing behind the “garden” that combines the urban and the natural. The shadow is a century of racial discrimination in the form of federal, state, and local urban development policies that built an environmentally sustainable and desirable playground for white upper-middle class people. Simultaneously these policies and city planning projects kept Black and Latinx people out of any real decision making processes, leaving them with the least desirable spaces in the city, spaces that remain underfunded and subject their residents to constant threat of removal and displacement.

Busch’s main purpose is to expose the complexities that arise when space is racialized through the process of urbanization. He foregrounds Austin as an exceptional case that further complicates the relationships between city leaders and developers, environmentalists, and the Black and Latinx communities as they all make claims for their ideas of how Austin’s space should be utilized. Furthermore, Busch suggests that the “history of human-environment interaction in Austin has revolved around managing water as well as enhancing access to and preserving unique environmental characteristics that have high use and exchange value” (14). This is apparent from the beginning of Austin’s city planning history.

From the late 1890s to the 1930s, city leaders focused on subduing the water system in and around Austin and successfully dammed the Colorado River. The project signified the capability of harnessing nature to provide residents, farmers, and especially companies with cheap power and flood control. In the 1930s, as the population grew, and new land became available to build on and to accommodate new types of labor, suburbanization and the Federal Housing Association (FHA) continued to place white communities’ needs above all others. While the FHA demarcated Black and Latinx spaces as “dilapidated” and ripe for redevelopment, the Home Owners Loan Corporation made sure that white neighborhoods remained white through restrictive covenants and other illegal methods that kept most people of color in south and east Austin. By the 1950s, rampant deindustrialization in Austin made working-class industrial jobs harder to get in the city. The process of ridding Austin’s inner city of heavy industry incentivized middle and upper-class labor and the companies that would employ them with new recreational spaces, the convenience of suburban life, and tax breaks for oil and high-tech companies. For Black and Latinx communities, the removal and redevelopment projects that resulted from mid-century urban renewal only served to exacerbate racial segregation as new housing was built on the east side of Austin.

As the book enters the 1960s, Busch strengthens his argument. Austin’s environmentalists started to challenge urban and environmental projects that posed a threat to the natural environment and recreational spaces. The best example here is their fight to ban motorized vehicles from the west side of Town Lake while the east side had to contend with massive motorboat races that drew thousands of people throughout the year and posed a threat to Latinx communities. Destroying the east Town Lake community’s park to build a stadium for the races sparked the organization of people in the community as well as organizations active in the Chicano and Civil Rights Movements. After six years of protest, the city finally moved the boat races without the aid of white environmentalists who never considered the negative effects that their efforts had on Latinx communities. Overall, the 60s and 70s proved that liberalism fell short for marginalized communities and white environmentalists only considered natural spaces as an environment in need of protection from city development projects.

In the 1980s, Austin leaders began to aggressively diversify the local economy as defense, oil, and high-tech industries effectively sparked the process of globalization. The University of Texas was integral in this economic transformation and supplied these new industries with skilled labor and state-of-the-art research capabilities funded mostly by federal defense contracts. This massive shift caused the city’s white population to expand residential areas in the north and the west. While these residential areas began to threaten physical spaces that environmentalists considered pristine and worthy of protecting, Black and Latinx residents living to the east and south saw production facilities move in to their neighborhoods making life more hazardous.

In examining the 1990s, Busch focuses on the bifurcation of the environmental movement in the fight against aggressive private and federally funded urban expansion. Traditional white environmentalists took on the encroachment of private development in pristine and untouched natural space. For this group, unchecked development threatened the Edwards Aquifer, an essential source of water and important part of Austin’s ecosystem. East Austin environmentalists agreed that the aquifer needed protection but added that their communities needed just as much protection from both old and new environmental hazards facing Black and Latinx people. For eastsiders, environmental injustice was a civil rights issue. They constructed “the environment as a hybrid landscape, one where natural and built reinforced one another and combined to undermine minorities health and access to jobs, education, and recreation…” (226). But, as Busch argues in the epilogue, eastside environmentalists lost to their white counterparts as the 2000s saw an increased development in east Austin because building east would not disturb any protected environments, eased the increasingly expensive housing crisis, and proved to be extremely profitable. Using the epilogue as a kind of policy proposal, Busch argues for a more equitable city planning and economic structure by way of creating jobs that do not just serve a certain sector of Austin’s growing population. He asserts that historical exclusion should be met with contemporary inclusion in every aspect and that gentrification poses an immediate threat to impoverished communities who are already being pressured to leave because of a lack of economic opportunity. Busch suggests that rent control, direct subsidies, and other mechanisms should be employed to create “a holistically livable environment” for all Austinites.

Busch’s book is important for students in a variety of disciplines, residents interested in city development and planning, city planners, housing and economic justice activists, as well as environmental activists. City in a Garden also leaves the history of Austin ripe for further research. In what ways did Black and Latinx residents challenge, participate, and/or survive the growing spatial disparities of their white counterparts? A research project on the historically Black Wheatsville community could provide some answers. What was life like in pre-WWII Austin for residents living in areas affected by environmental changes and hazards? An inquiry in to Mexican agricultural workers living in colonias around Austin might shed light on how changes in Austin’s economy – transitions from agricultural, to industrial, and in to oil and technology – affected where Latinos’ in Austin lived and worked over time. Readers interested in education might also be intrigued by the brief mentions of educational segregation and its lasting problems in Austin. With a hundred-year historical sweep the questions this book fosters seem endless, which is an excellent problem to have.

Overall, City in a Garden reveals a complicated past littered with good and bad decisions in hopes that people in the present and future might reckon with and correct the inequality literally built in to Austin’s city limits.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

You might also like:

Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and Ecology of New England

The Environment on History and the History of Environment

Also by Micaela Valadez:

Dreaming with the Ancestors: Black Seminole Women in Texas and Mexico