by Matthew Bunn

Civility may appear in short supply in today’s political environment, but “civility” as a standard for policing speech is currently in the headlines. For U.S. universities, the turmoil in recent years over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has renewed calls for civility, not as a voluntary norm of speech, but as a criterion for punishing speakers. As Ali Abunimah writes, “civility crackdowns are now breaking out across the country.”

On September 9, Inside Higher Education reported that a memo from UC-Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks had incited outrage both among the faculty and online commentators for suggesting that free speech was contingent upon its “civility.” As Dirks said, “simply put, courteousness and respect in words and deeds are basic preconditions to any meaningful exchange of ideas.” For critics of Dirks, it is not that civility is undesirable so much as the implication that uncivil speech forfeits free speech protections that has them upset.

Dirks issued his call for civility in light of the controversy that erupted when UIUC Chancellor Phyllis Wise rescinded a tenured job offer to Prof. Steven Salaita. As word of Salaita’s case spread through academia, a growing chorus of voices denounced the firing as a violation of academic freedom. At issue were a series of tweets, in which Salaita expressed hostility to Israeli military actions in Gaza that some critics denounced as anti-Semitic.

As Wise’s recent statements have revealed, she acted under pressure from major donors to UIUC who protested Salaita’s hiring, and the Board of Trustees notified Wise they would not approve the hiring, even as such approval is normally pro forma. Pressured on the other side by academic boycotts and letters from prominent scholars, Wise eventually forwarded the appointment to the Trustees, who voted 8-1 on September 11 to reject Salaita’s appointment.

L’affaire Salaita has reignited debates about the role of academic freedom, employers’ power to police employees’ speech, and the status accorded social media communication. Yet as relevant as new platforms like Twitter are to contemporary cases, conflict over the rights and responsibilities of academics’ public speech are as old as the modern research university itself. In fact, looking back two centuries ago and a continent away sheds surprising light on current issues.

Historians generally agree that the modern research oriented university originated in Germany in the early nineteenth century. The University of Berlin, now known as Humboldt University, was the first to require the defense of a piece of original research—the dissertation—to grant Ph.D degrees. Along the way, German universities pioneered research seminars, methods of primary source research, and other features of the modern research institution. German methods spread internationally once German universities became magnets for foreign, especially American students.

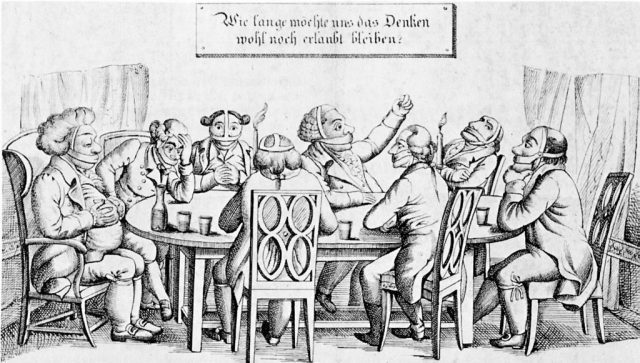

“The Thinkers’ Club (1819). A famous caricature refers to the Carlsbad Decrees, which were implemented at the behest of Clemens Prince von Metternich. The decrees suppressed nationalist, liberal student fraternities and imposed tight restrictions on freedom of expression. The sign reads: “Important question to be considered in today’s meeting: How long will we be allowed to think?”

Yet this period of German intellectual flowering also coincided with significant tension between the universities and the monarchical states. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the princes of central Europe set about stabilizing their power after decades of war and revolution. Universities were hotbeds of political, religious, and intellectual ferment. Student fraternities, often mentored by radical professors, became leading exponents of the cause of German national unity and constitutional government. Since all German professors were government employees, though, they faced grave risks to their careers for supporting the political opposition. A generation of scholars was blacklisted from German universities in the 1820s, while others labored under constant police supervision and censorship.

German governments had a hard time disciplining their unruly professors for many of the same reasons that modern university administrators like those at UIUC do: organized pushback from the faculty and allies in the press. When Wise withdrew Salaita’s offer, she faced withering criticism, including multiple no confidence votes from university faculty. Similarly, when Duke Ernst August fired seven professors at the University of Göttingen in 1837 for publishing a letter critical of his violation of the constitution, the German public sphere erupted in protest. Both causes galvanized supporters following the cases in the press, drawing the focus away from the content of the speech and towards the rights of academics to express unpopular or inconvenient ideas.

When it came to policing speech, German governments had a difficult time making hard and fast rules. For that reason, they tended to issue general guidelines about what writers could not attack—the security of the state, the Christian religion, and the personal honor of state officials—and left it to censors to decide what to allow, alter, or ban outright.

Left to their own devices, censors struggled to justify their decisions on the basis of laws or specific textual references. In many cases, censors banned works not only on the basis of content, but also the manner of presentation, which they called its “tendency”—essentially the tone of the work.

Here we see the affinity with contemporary demands for “civility.” Censors latched onto the idea of censoring tone because of how tricky it is to specify just which words or ideas are off limits. With reason, censors believed that passion, emotion, and humor made ideas more powerful to readers, and thus more dangerous. Appropriate writing was dry, objective, even-handed—“civil” in a bloodless sort of way. Anger and mockery, irrespective of the validity or merit of the argument, were to be discouraged.

The problem for censors, though, is that judging a writer’s tone is more subjective than simply looking for forbidden words or ideas. Authors like Heinrich Heine made a name for themselves by mocking the follies of authorities through sophisticated literary tactics. Moreover, censors—like modern day college administrators—were condemned for allowing their own personal judgments and prejudices to color their decision making.

Critics of censorship seized upon this subjectivity to argue that censorship was unworkable and intrinsically unfair, simply a way for powerful people to silence speech they personally did not like. Critics like the radical author Gustav Struve argued that censors simply cut anything well-written enough to become popular with the public, while philosopher Arnold Ruge lamented that censors would cut in one moment what they permit in another, all on the basis of personal whim.

In nineteenth-century Germany, ideas of universal rights of free speech were new and not widespread, but among professors and university-educated elites, the defense of academic freedom was better known and more widely supported. As a result, the cause of professors and scholars was often the mostly loudly trumpeted when it came to challenging censorship.

Facing criticism from an increasingly active public sphere, German governments protested that they respected academic freedom and the freedom of speech, but only within limits. Here again, tone and civility were key for justifying censorship. When the Prussian government issued revised censorship regulations in 1842, Karl Marx immediately attacked them, in his first published writing no less, as “pseudo-liberalism.”

Demanding that scholarly writings be “earnest and modest,” the Prussian government in Marx’s view imposed on scholars’ work conditions that had nothing whatsoever to do with truth. The tone of a work, Marx noted, is dictated by the nature of the subject—ridiculous things ought not be taken seriously, serious injustices not protested modestly.

Civility as a conversational virtue has much to recommend it. The enforcement of civility, however, especially among classes like academics particularly inclined to advance challenging ideas, should make us recall how the use of “tone” as a criteria for controlling discussion works. As the example of nineteenth-century German intellectuals suggests, what may appear an effort to reign in abusive language can quickly become a powerful tool for the suppression of speech. Let us all be civil—and accepting of a little incivility too.

Images via Wikimedia Commons