by Julia Rahe

The modern individual, living in an era of high-speed technology, international travel and an increasingly worldwide community, may be surprised to learn that there have not always been only four time zones in the continental United States, or that there existed a era when having one’s picture taken was an anomalous, threatening experience. Stephen Kern’s fascinating book, The Culture of Time and Space, investigates these and other radical changes that occurred in people’s temporal and spatial reality at the turn of the twentieth century. Kern calls time and space the universal, “essential” realities through which humans perceive, experience and live life, and he uses them to understand historical change.

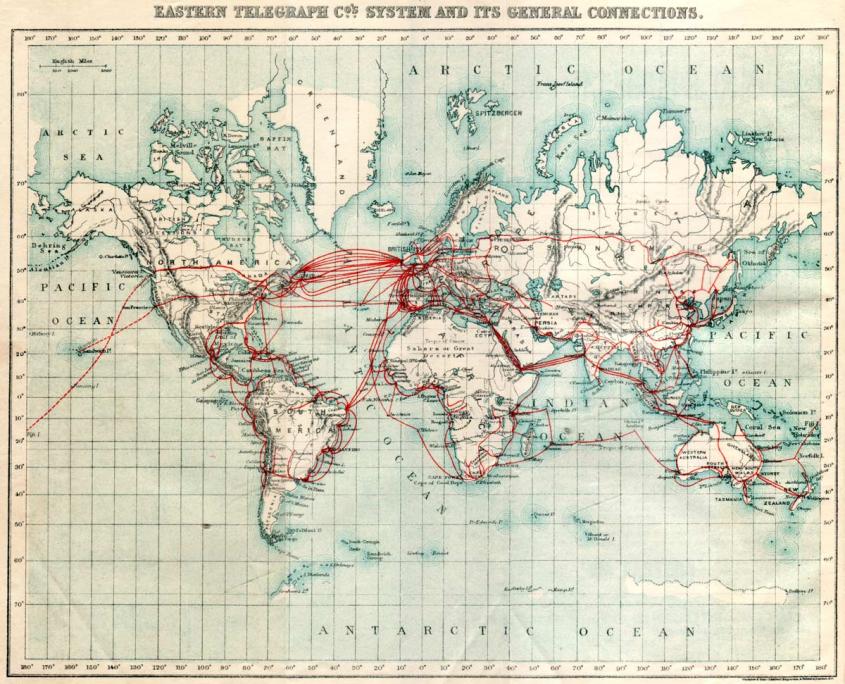

According to Kern, the forty years between 1880 and 1918 were a period of unprecedented cultural renovation and refiguring, when changes in perceptions of speed, space, form, distance and direction broke down traditional hierarchies and reconstructed conventional values and understandings. The proliferation of technological advances such as the telephone and the telegraph altered perceptions of time by allowing individuals in one place to experience simultaneous events in another for the first time. The result was a “thickening” of the present as events occurring in different places convened in a single moment. At the same time, advances in transportation created a “cult of speed,” as bicycles, trams and railroads allowed people to travel at faster velocities than ever before.

‘What hath God wrought’?: a map showing the global reach of the Eastern Telegraph Co. System, 1901.

While technological advances altered traditional understanding of time, cultural trends in art and philosophy challenged classical perceptions of space. New artistic movements such as Impressionism and Cubism broke down the illusion of three-dimensional space displayed on the two-dimensional canvas by presenting multiple perspectives to the viewer. These multiple points of view reflected the growing pluralism and confusion of the modern age. New philosophical trends such as Perspectivism also supported ideas about plurality and the subjectivity of personal experience by challenging the notion of an absolute, homogeneous reality.

New art movements such as Futurism, Cubism and Dadaism challenged old notions of perspective and drew inspiration from modern technologies such as the telegraph, the radio and the airplane. This detail from Umberto Boccioni‘s 1911 painting The Noise of the Street Enters the House exemplifies the frenetic energy of this new aesthetics based on speed, urbanism and technological prowess.

Through the juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated cultural and scientific phenomena, Kern successfully draws conclusions about broader social changes occurring across Europe and the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. The Culture of Time and Space is a captivating read for a wide audience. Kern’s broad and sweeping, yet detailed, discussion of new trends in art, philosophy and architecture will thrill lovers of material culture, and science and technology buffs will lose themselves in Kern’s explanation of the profound impact of new technological advances on individuals’ perceptions of the world.

All images in this review were published on Wikimedia Commons under a GNU free documentation license.