American slavery was a dynamic institution. And though slavery was mainly a system of labor, those who toiled in the fields and catered to the most private needs and desires of slaveholders were more than just workers. Although utterly obvious, it must be reiterated that the enslaved were indeed people. In fact, the nature and diversity of the institution of slavery ensured that bondpeople would experience enslavement quite differently. Aiming to highlight the variety of conditions that affected a bondperson’s life as a laborer, Swing the Sickle examines the workaday and interior lives of the enslaved in two plantation communities in Georgia—Glynn County in the lowcountry and Wilkes in the piedmont east of Athens.

My study of antebellum Georgia forces us to reconsider notions of “skilled” and “unskilled labor,” to see the impact of domestic violence on slave families, the trauma of separations and sales, episodes of “forced breeding” and the significance of religion and an informal economy amongst the enslaved. Swing the Sickle provides an incisive look into the plantation lives of enslaved women and men.

Historians have often seen the enslaved workforce as divided into two separate camps: the skilled laborers and the unskilled. This view segregates domestics and craftsmen from field hands.. “Skilled laborer” became loose shorthand for bondmen and “unskilled labor” was nothing more than a proxy for female, or “woman’s work.” But skilled labor was often women’s work, especially if we look at skilled labor as nothing more than one’s ability to do something well. Field labor, and especially intricate rice cultivation, was a form of skilled labor that crossed gendered lines. Women swung the sickle, mastered the hoe and plow, and operated the mechanical cotton gin, all tasks that required practice and dedication over time not restricted to a particular biological sex. Some readers are surprised to learn that bondwomen performed many of these backbreaking field tasks at rates that numerically exceeded their male counterparts. Women also engaged in crafts like sewing, cooking, and even nursing. These types of non-agricultural labor were essential to plantation operations and demanded a great deal of skill and time from bondwomen. Thus, as skilled and hence valued laborers, some enslaved women also enjoyed many of the privileges and prerogatives afforded to some male skilled workers. Molly, for example, though not a field hand, was a valued servant to the King family and therefore, gained the same geographic mobility through her frequent travels as other trusted, skilled bondmen on the same plantation. If we expand our definition of skilled laborer to include the various skilled tasks that women performed, many bondwomen fall into that category.

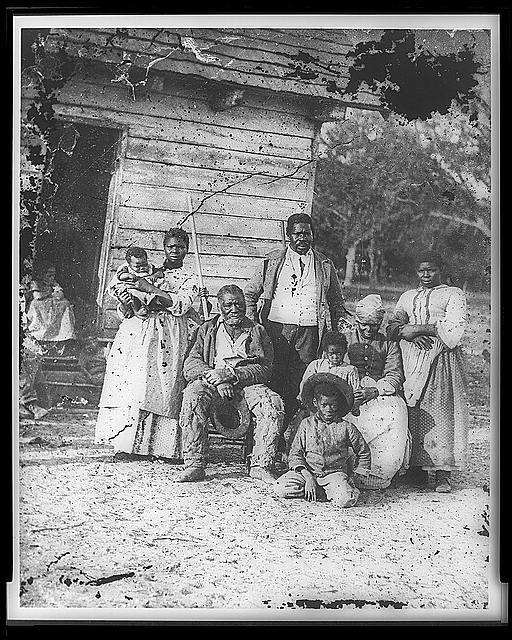

Aside from their lives as laborers, bondpeople in Wilkes and Glynn counties successfully attempted to forge fuller and more meaningful existences outside and around the dehumanizing institution of slavery. They built families and churches, and reveled in each other’s company during holiday feasts, corn shuckings, and during late night “working socials” and quilting parties. These social activities gave both bondmen and women an unexpected degree of automony.

Other experiences that fall outside the realm of work were intended to rob the enslaved of all autonomy and agency. Men and women were both subject to unwanted, coerced sexual activity. Sexual exploitation affected both bondmen and bondwomen. While it is well-known that enslaved women suffered immeasurable cruelties and gross sexual violations at the hands of slaveholders and other male agents of power within plantation communities, little thought has been given to enslaved men’s experiences with forced breeding. Bondmen were raped too. They were sometimes coerced into sexual relations with partners other than their wives or the women they courted, all for the slaveholder’s eventual increase in slave labor. That these men were denied a fundamental right to not only choose mates but to dictate the terms of their intimate relations with those mates was yet another debasing act of slavery.

Further reading:

The website produced by the National Humanities Center on daily life of slaves in the US.

More Reading on slavery in the US

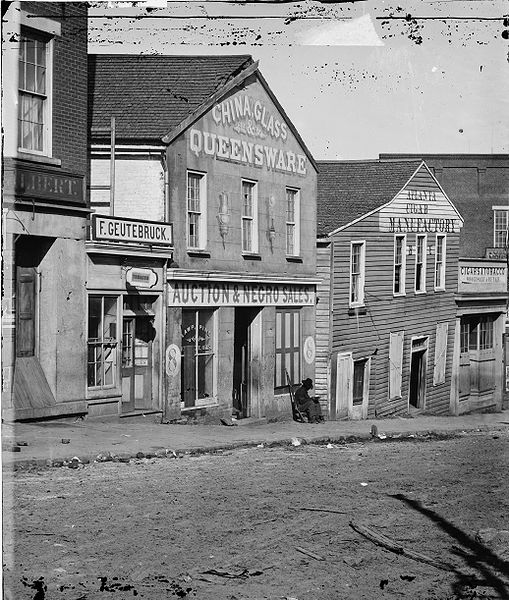

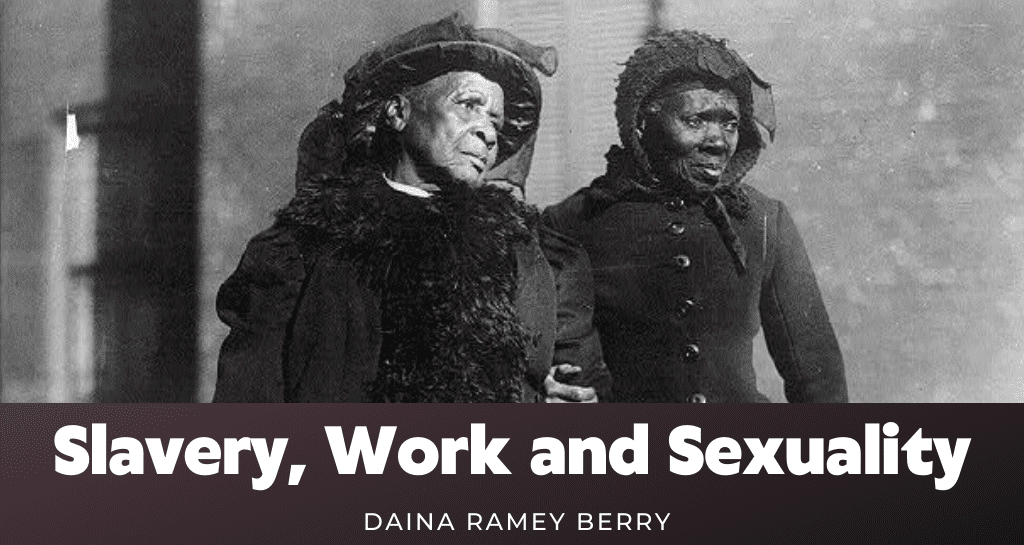

Photo Credits:

All originally: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Convention of Former Slaves, Washington, DC (LC-USZ62-35649)

Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Family on Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina, 1862 (Wikimedia Commons)

Julia Williams Wadsworth, Ex-slave, c 1937-38 (LC-USZ62-125156)

George N. Bernard, Scene in Whitehall Street, Atlanta, Georgia, 1864 via Wikimedia Commons