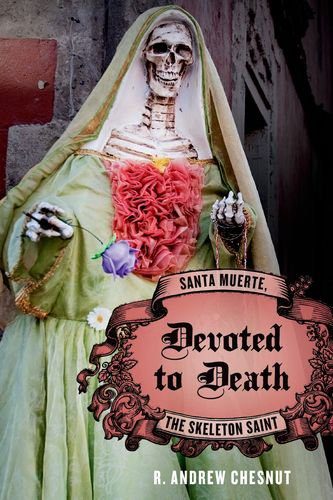

During a recent drug bust in Houston, Texas, officers discovered a shrine to a skeleton statuette, robed in green and holding a scythe wrapped in dollar bills in her right hand,  tobacco lying as an offering at her feet. Votive candles of various colors surrounded the statuette, as well as regularly replenished glasses filled with water and Mexican tequila. The officers had found Santa Muerte.

tobacco lying as an offering at her feet. Votive candles of various colors surrounded the statuette, as well as regularly replenished glasses filled with water and Mexican tequila. The officers had found Santa Muerte.

In Devoted to Death, R. Andrew Chesnut tells the tale of the recent rise in popular reverence for the Mexican folk “saint of death.” A non-canonized, non-sanctioned saint nicknamed “La Huesuda” (Bony Lady) and “La Flaquita” (Skinny Lady), Santa Muerte rivals Mexico’s beloved Virgin of Guadalupe in popular appeal, yet the majority of her devotees are drug kingpins, gangs, the poor and the dispossessed. Angel of death, protector of the impoverished, and provider of love, prosperity, and healing, Santa Muerte combines the powers of what is commonly considered magic, witchcraft, the occult, and religious tradition. Yet, rather than a lurid exposé of the cult surrounding this patroness of criminals, in his book Chesnut offers an insightful ethnographic exploration of the limits of “true” religion and of the practices outside its borders.

In seven chapters, each named for a color of candle lit to the Bony Lady, Chesnut recounts the rainbow of qualities ascribed to Saint Death, and the gifts she bestows on believers. Prayer requests to her must be accompanied by correctly colored candles, believers explain: red brings love and passion; purple, healing; gold, prosperity and abundance; green protection from – or through – the law. As is common in folk religions, Chesnut explains, the relationship between believers and Santa Muerte is “contractual” and based on reciprocity; devotees expect to be rewarded for their devotion. As “godmother and sister” Santa Muerte mends relationships and nurtures the weak, and as angel of death she metes out justice and vengeance. She is “a supernatural action figure who heals, provides, and punishes,” making her “the hardest-working and most productive folk saint on either side of the border,” in many ways “supplant[ing] God himself with her ability to perform miracles.” Perhaps most surprising, particularly for those who associate religiosity with peaceful, morally-focused living, is that though her devotees come from all walks of life, Santa Muerte has a significant following among Mexico’s notorious narcos. Criminal cartels light black candles to her for protection – both from rivals and from the reach of the law – and for death and vengeance to their enemies. Though she is decidedly not an orthodox Catholic saint, devotees model their ritual observance of her upon traditional Mexican Catholic practices, creating shrines with robed skeleton statuettes, leaving devotional offerings – often of tobacco or marijuana – and, of course, lighting votive candles.

Worshipers of Santa Muerte raise devotional dolls to the deity in Mexico City (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

An ethnographic work based largely on personal interviews and media research, Devoted to Death is written for popular readers. The lack of historical context, along with scant citations, minimal background research or discussion of devotional practices generally, will frustrate scholars. Still, though it is more of a jumping off point than a definitive work, Devoted to Death opens a new window on the nature of religion. Its unusual subject matter makes it a fascinating read.

Further Reading:

More images of the Santa Meurte from Time

And two Houston Press articles about the Santa Meurte: