by Tiffany Gill

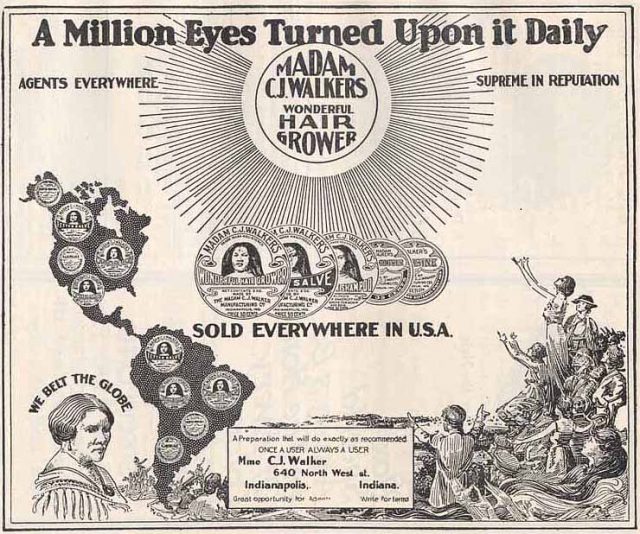

Black is beautiful. The Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s popularized this slogan and sentiment, but almost half-a-century earlier, black beauty companies used elaborate advertisements like the one pictured here to sell their vision to uplift and beautify black women. African American women like Madam C.J. Walker produced beauty products and trained women to work as sales agents and beauticians. and in the process, developed an enduring enterprise that promoted economic opportunities and connections with African descendant peoples throughout North and South America.

Some of the most effective marketing strategies of the early black beauty industry are on display in this Walker Manufacturing Company’s 1919 advertisement. Madam C.J. Walker, founder of the Walker Manufacturing Company, was one of the most important figures in the beauty industry and pioneered marketing strategies that shaped it for decades. While white owned beauty product manufacturers in the late nineteenth century advertised beauty products that celebrated skin lightening and hair straightening regimens, the products highlighted in the Walker advertisement featured hair growers and salves to combat dryness and other scalp ailments. African American consumers were more compelled to support companies that did not address them as though their darker skin and highly textured hair were things to be fixed, but instead bought beauty products that promoted healthier hair and scalps.

Although Madam Walker died unexpectedly just before this advertisement was featured in the Crisis Magazine the official mouthpiece of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Walker’s influence dominates. In fact, Walker, in life and in death, was the most effective advertising tool for her company. Born Sarah Breedlove in Delta, Louisiana in 1867, Walker was orphaned by age eight and a widowed mother of a two year old by age 21. When left with the responsibility of raising her daughter on her own with little formal education, Walker found employment in one of the few areas available to African American women—domestic labor. After moving to St. Louis, she became increasingly frustrated with her limited economic prospects as a washerwoman and began working part time as a sales agent for the Poro Company, a beauty products manufacturing and educational company established by Annie Malone. While working for Malone, Walker claimed in interviews years later that she had a dream where she was given ingredients for a special hair grower to help African American women with the hair issues that emerged from poor diet and hygiene. Most likely, the product she eventually marketed as her “Wonderful Hair Grower” was a modification of a similar product offered by Malone. At any rate, with only $1.50 to her name, Walker and her daughter relocated to Denver and launched her company. When Madam Walker died in May 1919, her estate was valued at close to $700,000.

Walker’s humble beginnings resonated with the African American women she sought to reach with her products; her ascent to the African American elite made her a legend and an inspiration.

It is no surprise then that Walker’s image and name were emblazoned on every hair product and in every advertisement. Images of Walker’s well-coiffed, shiny hair, as well as the iconic image of her in the lower left hand corner of the advertisement looking regal, well-dressed, and tastefully accessorized, linked the use of these hair products with upward mobility and economic success. The Walker Manufacturing Company also promoted these principles by giving African Americans opportunities not only to buy the hair products, but to escape the limited labor opportunities that black women faced by becoming a sales agent. Proclaiming their desire to “belt the globe” and celebrating that they indeed had “agents everywhere,” opened up the possibility for black women to not only consume beauty culture, but to derive economic benefit from it as well.

Finally, the most striking aspect of this advertisement is in the way that it seeks to celebrate the building of an African American beauty empire that expands beyond the continental United States. For black entrepreneurs to travel across the United States to sell their products was not unusual. Black beauty pioneers like Madam Walker, however, traveled throughout the Caribbean and South and Central America to introduce women of African descent in these regions to their products and occupational opportunities. In November 1913, Walker traveled to Haiti, Cuba, Jamaica, Costa Rica, and the Panama Canal Zone. The trips were a mixture of work and play. Much of the black press coverage of her travels as well as her own accounts discusses her leisure and philanthropic activities. Still, the desire for entrepreneurial expansion was never far from her mind. For example, after returning from Haiti, Walker encouraged “the Southern Negro with money” to invest in the uncultivated soil of Haiti to introduce “progressive American customs and habits.” By 1919, Walker’s company had indeed made significant inroads throughout North and South America as the advertisement indicates. This hemispheric reach was a source of pride for the company and allowed black Americans to feel connected to people of African descent throughout North and South America through their shared consumer experience.

The image of Madam C.J. Walker’s “Wonderful Hair Grower,” shining like the sun, rising above the nations, boasting about its supreme reputation, continued to draw black consumers in large numbers until the 1930s when the Great Depression and increased competition caused the company to lose its dominance in the beauty world. Still, the pioneering work of Walker and her company helped to facilitate a black beauty and hair care industry that is now valued at over four billion dollars. Madam Walker helped many realize that black is not only beautiful, but profitable, too.

For more on the black beauty industry, you can read

Tiffany M. Gill, Beauty Shop Politics: African American Women’s Activism in the Beauty Industry

The official biography of Madam C. J. Walker

African American Women at Duke University Libraries

Ava Purkiss on Michele Mitchell’s Righteous Propagation right here in Not Even Past

Interesting portrait of Madam C. J. Walker by the artist, Sonya Clark, at the Blanton Museum of Art

The advertisement is published with the kind permission of A’Lelia Bundles/Madam Walker Family Archives/madamcjwalker.com. It is not to be reproduced for any purpose without permission.