Foreword by John Gleb

This is the first half of a two-part article. To read the second part, click here.

Ivonne del Valle (University of California-Berkeley), Anna More (Universidade de Brasília), and Rachel Sarah O’Toole (University of California-Irvine) are prominent scholars of colonial Latin America. Earlier this year, they sat down with Fernando Gomez Herrero (University of Manchester) to discuss a project they had worked on together, a book entitled Iberian Empires and the Roots of Globalization (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2019). The book is an edited collection which was published as the 44th volume in the University of Minnesota’s Hispanic Issues series.

In the following interview—part one of two—del Valle, More, and O’Toole discuss the origins of their project and identify its principal intellectual goals in conversation with Gomez Herrero.

The interview sheds light on the process by which scholars from different disciplines come to produce new scholarship and the challenges and clear benefits of collaborative work. As they explain, “Rather than arrive at a singular vision of early modern Iberian globalization or fold each case study into an unified narrative, the collaborative process required that we had to take each other seriously as peers.”

Equally interesting, the interviews wrestle with the complicated imperial context of globalization. As its title suggests, the book seeks to show the “Iberian roots of globalization,” while at the same time, the authors seek to give globalization its “proper dimension” by “displacing the Iberian metropolis, to focus on the important role of other locations in the process of creating global networks.”

The relationship between globalization and imperial power seems eerily familiar today. Del Valle, More, and O’Toole recognize this. In the interview below, they frequently draw connections between past and present, noting the ways in which the lived experiences of millions of people continue to be shaped by the political and cultural projects highlighted in their book. The authors argue persuasively that the centuries-old subject matter of colonial Latin American history is in fact imbued with deep contemporary relevance, especially for teachers and their students.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: Let us revisit and rethink the work done. This is about the genesis of the collaboration about this specific work [e. g., Iberian Empires and the Roots of Globalization]. How did you put together this edited volume that comprises eleven articles, or chapters, the three of you included, plus an afterword of two others? Something is already mentioned in the Acknowledgements.

Rachel Sarah O’Toole: In 2010-2011, Anna and Ivonne convened junior and senior literary scholars, historians, and art historians as the University of California multi-campus “Early Modern Globalization: Iberian Empires/Colonies/Nations” group to discuss their current works-in-progress. Inspired by the interdisciplinary collaboration, Rachel joined the long-standing duo (Anna and Ivonne have been close friends since graduate school). Together, we applied for a Mellon-LASA [Latin American Studies Association] Grant Seminar Grant with the goal to expand our participants beyond the United States and publish our collaborative research. The result was an intense week where we convened at the Museo Franz Mayer in Mexico City to discuss both our precis on early modern Iberian globalization and pre-circulated papers with scholars from Peru, Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, Italy, Mexico, and the United States.

During the workshop, how participants defined globalization, empire, and what or who constituted “Iberian” revealed our disciplinary boundaries, including where and when we had been formally educated, and what we thought was at stake in scholarly work. At the same time, the group immediately began to discuss a generative tension between institutional boundaries versus subaltern narratives or how there was a need for macro, structural accounts but also local particularities, period aesthetics, and individual people. As editors working with Hispanic Issues, then, the challenge was exercising patience with the texts and the narratives of our contributors, including ourselves, that could be described as baroque, jazz history (Elsa Barkley Brown 1992), or hybridity (Dean and Leibsohn 2010). Rather than arrive at a singular vision of early modern Iberian globalization or fold each case study into an unified narrative, the collaborative process required that we had to take each other seriously as peers. The process included multiple debates of terms, sharing scholarship, and repeated revisions that respected rather than flattened the particularity of text, time, and place.

Rather than arrive at a singular vision of early modern Iberian globalization or fold each case study into an unified narrative, the collaborative process required that we had to take each other seriously as peers. The process included multiple debates of terms, sharing scholarship, and repeated revisions that respected rather than flattened the particularity of text, time, and place

Ivonne del Valle: The conversations at the workshop in Mexico City (not always smooth, but the disagreements were also enriching) made us think about the field (colonial/early modern), from different disciplines, and perspectives. What is crucial for an art historian, for a historian, or for a literary critic, is not always the same, nor are the questions we ask from the documents we read, and from the field. The concepts we tend to value, the topics, all of these differences are valuable but as we learn, can also be bridged, sometimes. In general, people from different disciplines usually don’t have the opportunity to engage in this type of conversations about our field, and the approaches we value, about ways to collaborate. Another aspect that must be mentioned is the participation of the three of us at Instituto Tepoztlán (an international collective of academics at all stages in our careers—from graduate students to professors—that meets at a yearly conference in Mexico). We all have benefited immensely from the open debates and discussions their organization foments. And are indebted to them.

In these encounters we realized that one of the topics that kept coming back had to do with the question of globalization as it pertained to our period. When and how did it start? We were in agreement that the roots of the form of contemporary globalization could be found in the early modern period. We decided to answer it in a collective way with some of the people we had previously been engaged in this process initiated in 2010.

Putting the volume together was not an easy task to the extent that we wrote the Introduction as a team, and that meant a lot of back and forth, revisions, discussions. Each one of us also read all the papers, and we have different editorial practices. You can imagine that part. Nevertheless, at the end I think it was all worth it, the authors were patient with us, and understood the nature of the collaboration. Equally important is that we had three people (in addition to each author) agreeing that the articles were ready to pass to the review process of the press. Now I don’t remember clearly but I think that our own demands made the process easier with the press afterward.

Anna More: One thing that I would like to add to all that has been said is that from the beginning of our collaboration, we very consciously sought out interdisciplinary dialogue. Not only was that a main goal of our initial UC Humanities working group on colonial Latin America that initiated our collaboration, but we were deliberate in seeking contributors from different disciplines for the seminar in Mexico City that became the volume. For the second seminar, we also sought out participants from across the Americas. Not only was this a stipulation of the LASA Mellon Grant we received, but we also felt that there are few academic spaces where true inter-American dialogue takes place. This has to do with the different realities of funding that clearly affect Latin American participation in LASA, for example. Through the LASA Mellon Grant we were able to bring scholars together from across the hemisphere and even from Europe. To find these scholars we had to activate our networks from over the years. That is where being a collaboration of three scholars with roots and contacts in different places was invaluable.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: So, is this about the narrative of “globalization” and reasserting the “Iberian roots” in it? In other words, Spain and Portugal go “earlier” or “deeper” or “first” . . . . So what? And then what? I suppose I want your engagement with the introduction written jointly and also ideally with the “afterword” written by [Raúl] Marrero-Fente and [Nicholas] Spadaccini, editors of Hispanic Issues.

We are, indeed, asserting the Iberian roots of globalization, while at the same time we’re interested in giving it its proper dimension by displacing Iberian metropolis, to focus on the important role of other locations in the process of creating global networks

Ivonne del Valle : We are, indeed, asserting the Iberian roots of globalization, while at the same time we’re interested in giving it its proper dimension by displacing Iberian metropolis, to focus on the important role of other locations in the process of creating global networks. This exercise had two aims. First, to remind us all (once more, in a repetition that is as trite as it is necessary) that several of us do our work in an Anglo-centered environment, and that oftentimes even for knowledgeable academics nothing happens, or happened, until it occurs in an English-speaking location. Second, to also remind us that being the first doesn’t always translate into a sense of pride. Perhaps the contrary is the truth, as it is in this case, in which globalization brought about (as we insist in the Introduction) the production of enormous inequalities that were not there before. But this does not mean that the Iberian empires, or its organic intellectuals, were not deeply and astutely (though perversely perhaps) immersed in answering questions that were relevant not only to Spain and Portugal, but to international law, commerce, etc.

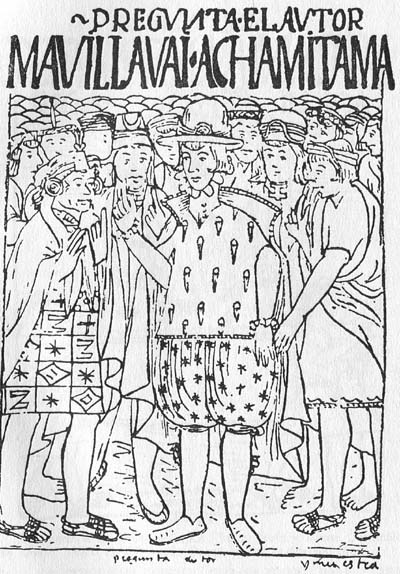

As for so what, I think that for those of us working in the U. S. it is clear that the changing origin of our students makes the period and the problems related to colonialism, immediate and contemporary. At least it is for them. One would think, for example, that sitting in a class where one has to read 16th, 17th, or 18th century materials in the original Spanish (as it happens in departments of literature) would not be desirable for young people. Nevertheless, the opposite is true. Students are engaged in the discussions and understand the stakes. Once, after a series of sessions on [Felipe] Guaman Poma [an Indigenous author from 17th-century Peru] and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega [another seventeenth-century Peruvian writer], one of my students suggested that perhaps in the future I’d realize how among those taking my class was the person who had become the 21st century Inca Garcilaso, who in the U. S. would compare this country to a Latin America, in order to uphold the latter. If colonialism and imperialism did not exist anymore, perhaps these types of courses and books would not be as relevant, yet imperialism continues to exist and to shape our experiences and it’s therefore important to understand it. As Marrero-Fente and Spadaccini remark in the “Afterword,” there’s a nexus among colonialism, imperialism and globalization. And I don’t think this has ever stopped being the case.

Anna More: I think that one important point to make is that like any ongoing and totalizing process, globalization is a term that can be interpreted through diverse structures and from vastly different perspectives. So, we were deliberate in our use of the term “roots” rather than “origins.” Origin suggests a singular genealogy, looking for the source of a current state. “Roots” is obviously more rhizomatic and multiple. This is not to say that there weren’t events or institutions that accelerated and centralized processes. This is where the “Iberian Empires” part of the equation becomes relevant. While we all acknowledge that Iberian monarchies were dispersed, they were also coordinated under legal frameworks, religious institutions and norms, and cultural and linguistic processes of homogenization. And these norms were not just suggested as a natural part of an equivalence or exchange, but indeed expected and mandated by institutions backed by force. Of course, that does not mean that there weren’t creative forms of appropriation of languages of power, modes of living under new social identities or genuine conversations to Christianity. And it is also true that Iberian institutions were competitive, focused on diverse and at times contradictory goals, or simply reactive to on the ground distinctions in the vast geographies of Iberian expansion.

Our challenge was to somehow reflect all of this messiness as well as the attempts to order it, both by Iberians and by non-Iberians. Even in a long volume it would be impossible to cover all the variations. But we wanted to combine geographical reach with disciplinary lenses to give a sense of the results of different approaches to diverse materials and questions.

We hoped that this exercise gives a sense of the interplay between the macro processes of, say, bullion flows that traveled to China or the Inquisition in its attempt to police religious practice in far flung regions, and the microhistories of the lives of those who were living in these regions and under these circumstances. I suppose that this has to do with a sensibility that we believe that all our contributors shared to exposing the mechanics of this sort of globalization in the interplay between the macro and the micro levels.

Finally, we were not necessarily interested in weighing in on theoretical versions of globalization or on lamenting or celebrating it.

Finally, we were not necessarily interested in weighing in on theoretical versions of globalization or on lamenting or celebrating it. I believe that if we had a certain affinity, it would be more in line with a world systems approach, however that would not account sufficiently for forms of meaning and resistance formed through culture and social relations. And while I think that we can all agree that the violent imposition of empire was disastrous for most of those living under colonial rule, that fact needs to be complemented by the ways that a shared trauma or circumstance created new political modes. These modes go beyond a search for “resistance,” a term that ultimately reifies structures of power, and into realms that might not even be fully legible for us as historians. In other words, our collective challenge is to remain open to meanings that were generated in the vastly different regions that Iberians attempted to incorporate into their monarchies.

Rachel Sarah O’Toole: Still, for me, one problem that remains is the deep attachment that we continue to maintain to the organizing possibilities of empire. I include myself! The challenge, however, is how we include or narrate the empire. I wonder if we could stop positioning the empire, or the state, or Spain as the main actor in our historical narratives. Even reviewing recent publications for this interview, I was struck by how many continue to employ the same framework of Iberian triumphal expansion. For historians, partly, the focus on Spain, or the Crown has to do with our dependence on archives produced by state institutions that, in turn, shape our narratives. It is no wonder, then, that in their “Afterword,” Marrero-Fente and Spadaccini emphasize the European institutions of our volume including Jesuit networks, global trade, imperial laws, and racial discourses that presumably provide the required “sweeping conclusions” (333) for contemporary academic audiences. Yet, I would suggest that clerical orders, merchant guilds, policy makers, and colonial authorities produce what Western scholars expect as teleological narratives that are located and captured in the archives created by the empire for the empire. As a result, the story of the state has become the story we are most accustomed to hearing.

I, for one, cringe at my own narrative when I hear myself in lecture or when I write a sentence that begins with “Spain” as the central historical actor. After all, as Ivonne so eloquently and wryly observes, pride is not the emotion we associate with being the first. Why? Because the articulation of Spain, empire, or Europeans as the main actor is historiographically paired with the erasure, belittlement, and denigration of Africans and Indigenous people. As much as we worked to highlight the intellectual and religious contribution of Indigenous Andean people in our “Introduction,” the emphasis was on their labor, while Marrero-Fente and Spadaccini refer to enslaved captives as commodities (332) in the “Afterword.” Both examples call my attention to how we need to address the narrative or how we tell a story of empire, including the Iberian empire, without continually dismissing the political, cultural, social, and intellectual actions of Indigenous, African, and Asian people.

One answer is to simply, and radically, begin another empire at the center such as the Kingdom of Kongo as have John Thornton and Cécile Fromont. As Herman Bennett has reminded us so clearly and so eloquently, we need to see Africans and African-Iberians as theologians, merchants, courtiers, sovereigns, and intellectuals who disagreed, competed, conquered, and historicized from their own empires.[1] Another is to meticulously insert enslaved African and African-descent people as the central actors in the global institutions of the Spanish empire as disrupting global currency chains or providing the standard for early modern Christian piety.[2] Or, we could insist on the decentralization of empire and confront universalist assumptions by refusing, or at least, questioning the logic of connectivity. As Zoltán Biedermann points out, “there is a potentially pernicious politics to global and connected history writing, especially when it emphasizes trade or culture over war and exploitation.”[3] In our volume, we worked these tactics as Anna explains by including activities in Goa [a Portuguese colony in India] and Manila in our definition of an “Iberian” sphere or demonstrating how enslaved litigants shaped the rules of imperial documentation. In seeking a disavowal of the empire’s organizing function, perhaps an additional tactic is to investigate those who turned away from the sirens of empire that we are so readily able to document.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: Perhaps another way of saying the previous question is, how do we put together the various labels of “Iberian,” “globalization,” Hispanic and Latin America, imperial and colonial? Why bother? How does this “history” fare, say, in California and Brasília or elsewhere for that matter?

Ivonne del Valle: In the case of California, given the fact that Latinos comprise almost 40% of the total population, and that the University of California is supposed to be a public institution, I think it’s clear that we have a responsibility to educate our students about the countries they come from (Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, etc.), and also about the legacy of political projects than continue to affect them in the 21st century. Learning about history, theory, literature, and learning about them in a rigorous way doesn’t have to be an abstract, luxurious exercise removed from daily life. It isn’t for us, and it isn’t for many of our students for whom the “ivory tower” metaphor simply doesn’t make any sense.

Given the highly unequal nature of Latin American societies, I’m sure that the topic of colonialism in its 16th-18th century avatar or in its more contemporary forms, remains entirely relevant. It is at least in the case of Mexico. Not all inequalities are related to colonialism, of course, but some of the most salient are: racism against Indigenous and African people, with all this entails: From the institutional treatment of these communities (lack of hospitals, schools, running water, all basic services, etc.) to the continuous despoiling of their lands, their water, forests, etc. The fact that in recent demonstrations in Chile, for example, and in Santiago and not in a “remote” rural area, waving an [Indigenous] Mapuche flag was the chosen symbol, is very telling. The same can be said about the recent destruction of statues and monuments of Spanish conquistadors all over Latin America, the U.S. included. Latin America continues to have an immense debt to indigenous and African populations.

It is also important to understand the role of processes that unevenly connect a small town in a Latin American country to places such as California. Why do people in a farming community in Mexico, or Guatemala end up going to California? Perhaps because the economic treaties and the demands of international trade, put an end to the possibility of living there in a way that might seem opaque, but which consequences are very real: all of a sudden a big agroindustry working for the U.S. market takes up all their land and water (with the help of their local and national governments), and these communities all of a sudden are left to fend for themselves. This is a clear effect of globalization (and imperialism, and internal colonialism). The U. S. is a chosen place to migrate to, not only because it’s closer than say, Amsterdam, but also because it is also the place to where all good things go: the best crops, the best produce, etc. The image of incredible wealth is not gratuitous. And people who can no longer work their own land, have to go elsewhere in order to sustain themselves and the communities they left behind.

Rachel Sarah O’Toole: Picking up on Ivonne’s attention to our shared student body at the University of California, I think the point is to revisit what we mean by “marginal” or “minority” within an imperial or colonial framework. In southern California, my students and I are incredibly conscious that we are learning, living, and working on unceded lands of the Gabrieleños and Juaneño-Acjachemen Nation, stolen from Mexican ranchers in the nineteenth century, usurped from Japanese farmers in the twentieth century, and currently operating under the logics of redlined, sundown towns to Black Californians. So, a narrative that a Spanish or Iberian empire would “reach” or “embrace” or “define” a geography and its populations that stretched from the Mediterranean to the South China Sea simply does not make sense to the diasporic, multilingual, and brilliant BIPOC students who talk to me on the daily.

So, a narrative that a Spanish or Iberian empire would “reach” or “embrace” or “define” a geography and its populations that stretched from the Mediterranean to the South China Sea simply does not make sense to the diasporic, multilingual, and brilliant BIPOC students who talk to me on the daily.

As a result, I have been challenged by what dissent means within the Iberian empires. Hardly a Gramscian hegemony and certainly not confined to a Marxian teleology, my students are suspicious of concepts, actors, and logics that are defined as dominant. As Ivonne suggests with her example of Guaman Poma, students ask me why wouldn’t a dissenting text, hybrid art, and or an enslaved person define legal freedom, natural rights, and ecclesiastical aesthetics? So, in answer to Fernando’s question of “why bother,” we need revised frameworks of empire, globalization, and colonialism that center the majority of experiences but also grapple with dissent in a non-binary manner. Bringing Amerindians, Blacks, and Latinos “into the narrative as ‘minorities,’ whose voices need to be heard, is itself complicit in their marginalization” as Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra so eloquently explains, is not the end game.[4] Instead, the goal is to shift the narrative, change the frame, or move entirely to a new sphere. In his edited volume “Entangled Empires,” Cañizares-Esguerra asserts that without Latinos, or without the Spanish Americas, the previously hermetically-sealed Anglo Atlantic world simply could not exist. Indeed, what Cañizares-Esguerra suggests is not just a corrective to Eurocentrism, but a change in who is at the center of our narratives and how we tell the story. Along with Cañizares-Esguerra, our goal, then, is to challenge a clean, homogenizing, and Eurocentric narrative of empire. Instead, I suggest a generative story recognizable to many of our students: that of dissent, disorder, or the queer, without which the empire simply could not function.

Anna More: This is an interesting question for me as it forces me to articulate from “where” I am researching. Mid-way through our process from seminar to publication I moved from the University of California to Brasília, where I now teach at a large public university. The move has entailed many challenges but even more gains. Clearly, academia is a globalized institution, which obviously is not to say it is homogenous. Of course, universities in Latin America are constantly battling for funding and this affects many research possibilities. But then, there are creative ways to address those limitations. I cannot count on the library at my university, but the Brazilian government pays centrally for good journal access. I have friends who send me pdfs that I can’t get and I also buy books on kindle if I’m desperate.

Yet my reality is still privileged, both in terms of Latin American universities, which do not all have even the funding that Brazil provides, and in terms of my networks and ability to travel. And if these challenges exist for university professors, they are clearly worse for my students. There are all sorts of gatekeeping functions, from ability to read research published in English to more basic obstacles like computers and bandwidth. And yet, my students are reading [sixteenth-century social reformer Bartolomé de] Las Casas and Guaman Poma and Sor Juana [Juana Inés de la Cruz, a seventeenth-century polymath from colonial Mexico] and having strong reactions of curiosity, identification and illumination about deep structures of race and gender, for instance.

It’s important to realize that in Brazil, democracy is young and my students are the first generation to fully grow up under the 1988 constitution. We are also living through an extremely destructive presidency and, of course, the global pandemic. The university feels like an oasis, but it is under attack and holding out against vindictive funding cuts. At the same time, all of this is retribution for the gains made under the previous administration. Over the last twenty years, our student body became more diverse, more engaged with questions of race, class, and sexuality, and thus more curious about their deep history in Brazil and Hispanic America. I suppose that what is most surprising to them is that processes from 500 years ago are so recognizable today. What is striking is that for them, it’s the university that is the portal onto the world, especially for students studying Spain and Spanish America. For many, this is an alternative to U. S.-centric globalization that surrounds them on a daily basis.

So, in terms of the “so what” question, I think that there is one answer as researchers in dialogue with global academia in which it is important to bridge colonial Iberian studies and theoretical and historical debates that often have presentist or anglophone blindspots. There is another answer if we are thinking about students who are themselves trying to understand processes of globalization, including the politics of democratization and social justice. I think that what our answers all show is that the second is as important if not more important a “so what” as the first.

[1] Herman Bennett, African Kings and Black Slaves: Sovereignty and Dispossion in the Early Modern Atlantic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

[2] Larissa Brewer-García, Beyond Babel: Translations of Blackness in Colonial Peru and New Granada (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 198; Molly Warsh, “Assessing Worth across the Iberian Empires: Pearls and the Role of Human Capital in the Creation of Value, c. 1500-1700,” The Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 19:2 (Spring 2019), 63, 65.

[3] Zoltán Biedermann, (Dis)connected Empires: Imperial Portugal, Sri Lankan Diplomacy, and the Making of a Habsburg Conquest in Asia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), ix.

[4] Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, “Introduction,” Entangled Empires: The Anglo-Iberian Atlantic, 1500-1830, Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, editor (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 4.

Fernando Gomez Herrero (Spain, US; PhD (Duke University), MA (Duke U, Wake Forest U, U of Salamanca), B.A. (U of Salamanca). He has taught at Duke, Stanford, Pittsburgh, Hofstra U, Oberlin College, etc. Relocated in the U.K, he has taught at the University of Birmingham and the University of Manchester in the last four years. His book Good Places and Non-Places in Colonial Mexico: The Figure of Vasco de Quiroga (University Press of America, 2001). He is working on a volume tentatively titled The Hispanic Misnomer in the Anglo Zone: Public Conversations (2001-2022). Latest publications include: “The Latest American Appropriation of Western Universalism: A Critique of G. John Ikenberry’s “Liberal International Order,” included in Rethinking Sovereignty and Territoriality in the 21st Century (http://journal.thenewpolis.com/archives/1.1/index.html ; Inaugural Issue, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Winter 2022), Decoloniality and the Disintegration of Western Cognitive Empire: 90 pages.site: https://www.fernandogherrero.com. He has recently collaborated with the Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia covering international news, particularly U.S. and U.K. (https://www.lavanguardia.com/autores/fernando-gomez.html , in Spanish).