Foreword by John Gleb

This is the second half of a two-part article. To read the first part, click here.

Ivonne del Valle (University of California-Berkeley), Anna More (Universidade de Brasília), and Rachel Sarah O’Toole (University of California-Irvine) are prominent scholars of colonial Latin America. Earlier this year, they sat down with Fernando Gomez Herrero (University of Manchester) to discuss a project they had worked on together, a book entitled Iberian Empires and the Roots of Globalization (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2019). The book is an edited collection which was published as the 44th volume in the University of Minnesota’s Hispanic Issues series.

In the first half of their conversation with Gomez Herrero, del Valle, More, and O’Toole discussed the origins of their project and identified its principal intellectual goals. The following interview reproduces the second half of the conversation, which saw the three authors dive much deeper into the contents of their book. Their comments identify the most important themes to emerge from Iberian Empires and the Roots of Globalization, describe some of its constituent essays, and reflect on perspectives the book overlooked—and where colonial Latin American history is headed next.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: Which specific aspects, favorite themes or unmissable issues would you like to highlight in relation to this collective volume? Is there a magic thread, a line of peas to follow? The acknowledgements make mention of María Elena Martínez [1966–2014, an historian of colonial Mexico].

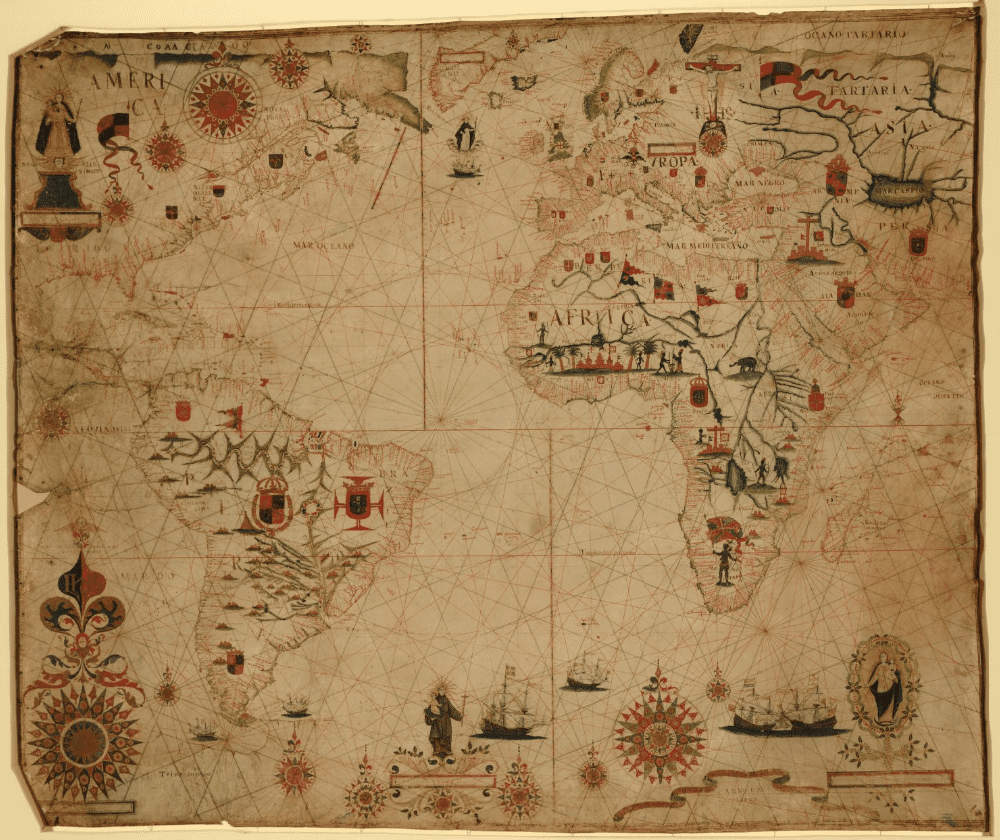

Ivonne del Valle: From my perspective, I’d like to believe that María Elena Martínez (a colleague and friend from Instituto Tepoztlán [an annual conference on the transnational history of the Americas]) looms large. I hope that the combination of rigor, and imagination she shared with us, is clear in the work as a whole. Beyond this, there are other threads I’d like to foreground. One of them is the engagement with theory, and the postcolonial inflection of the volume. Another one is the attempt to look at globalization and its universalizing aims from the perspective of the local. That is, [the] Iberian metropolis might have initiated certain processes, yet they did not have control over them. An important contribution in most of the articles is that of the dialectics between ideas and projects on the one hand, and the material realities that sustained them, or not, on the other. The gap between them was important for us.

By the same token, rather than trying to “tame” the complex dynamics of early modern/colonial globalization, we accepted the intricacies, and tried to make sense of them.

By the same token, rather than trying to “tame” the complex dynamics of early modern/colonial globalization, we accepted the intricacies, and tried to make sense of them. I think that because of that we’re offering a prism that coherently reflects how these initial and profound global contacts could provoke awe and genuine interest and curiosity in those involved, but that it was primarily a process based on exploitation that caused overwhelming chaos, in spite of the serious attempts (those of some religious orders, or art, for example) to give it a more humane face. [Hispanic Issues series editors Raúl] Marrero-Fente and [Nicholas] Spadaccini in the “Afterword” refer to art as that which turns history into myth and symbol. The myth of salvation is a powerful one in colonial art.

Rachel Sarah O’Toole: The welcomed challenge of this project has been how to articulate the political, cultural, social, and intellectual agency of Indigenous and African Diaspora people within empire’s superstructure. We had models to follow. For me, these included historians who have shown how Indigenous communities employed imperial legal institutions to their own benefit (de la Puente Luna 2018, Premo 2017, Stern 1982, Yannakakis 2008) as well as scholars who chart Indigenous authorship within the so-called Spanish lettered city (Adorno 1986, Rappaport and Cummins 2011). In the volume, you can find Guillermo Wilde, Ivonne, and Charlene Villaseñor Black expanding on how Guaraní and Nahua people employed Spanish missionary texts, colonial institutions, and artistic forms to defend, negotiate, and create their own intellectual projects. Rather than explain Guaraní and Nahua authors within a resistance paradigm, our hope is to showcase how indigenous communities shaped literacy and Christianity from their own realities.

The interdisciplinarity that is built into the volume and, I think, emerges subtly, in the keen attention that each scholar attends to the text. We were often easily lost in our initial conversations as the differences of language, discipline, nationality, generation, and other identifiers seemed overwhelming. Nonetheless, when we met in the Museo de Franz Mayer in Mexico City that houses a fantastic collection of decorative and visual art from the colonial period, our common meeting point was a mutual fascination with how each other was transforming evidence from distinct objects, documents, or data. Art historians Charlene Villaseñor-Black and Elisabetta Corsi point to the materiality, provenance, and skill necessary to create a shimmering mother-of-pearl inlay image or a porcelain statue. Literary scholars including John (Jody) Blanco call our attention to the exchange of translation evident in tracing a European medieval romance. Deftly, Bernd Hausberger’s paper referred to quantitative data while Bruno Feitler called on the testimonial echoes among Inquisition cases across vast geographical distances. We made a point, in the editing, to have the authors explain their methodological approaches to their texts, or how they extracted their evidence, in part to underline a shared scholarly agenda. For Anna and Ivonne, I think this question was boring! But, for other scholars, especially the historians, the result, I think, invited us to think even more creatively about texts that constitute, and explode, the boundaries of our early modern narratives.

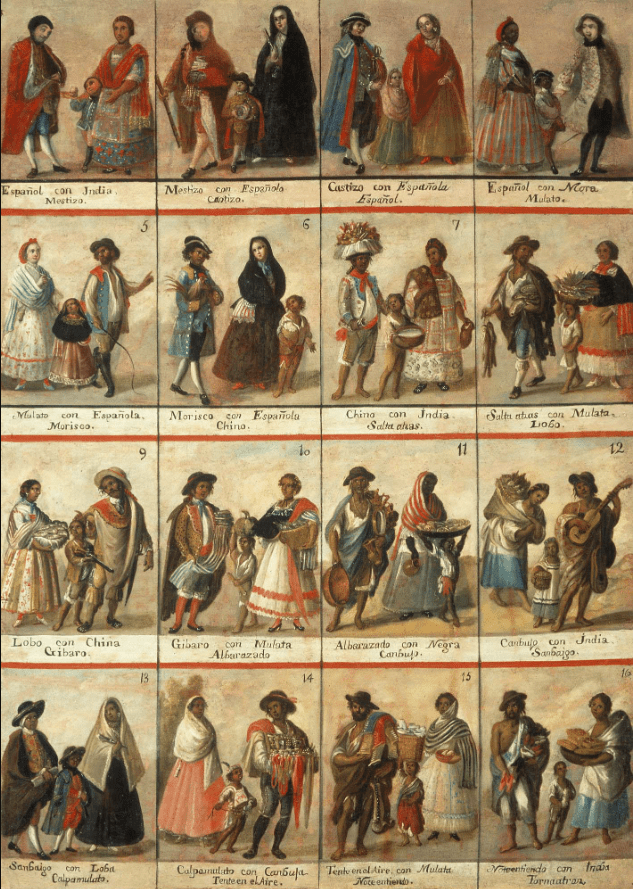

Anna More: I would agree that with Ivonne and Rachel. All of the chapters, in one way or another, provide a detailed discovery of an object and a problem in which documents from locales reflect globalizing processes: long-distance connections, universalizing norms and at times violent mandates. In this sense, Maria Elena Martínez’s chapter is exemplary as she took her vast knowledge of processes of racialization in New Spain and pushed them out to further geographies. This was one of the last pieces of writing of María Elena’s to be published and as such it is at once so important and so hard to see it in print. But overall, it shows the carefulness in interpretation necessary to avoid sweeping generalizations and find surprising narratives in the past.

In this sense, for me, there is also a very important line that runs through various chapters: practices that are products of globalization but whose meaning is enigmatic. In a sense, this is more of a norm than an exception. That is, globalizing processes that are centralizing or subordinating can be very clear. Reactions or proactive connections outside or beyond these processes tend to be very opaque to us. I think this is particularly the case with literature and art and for this reason, I would highlight the chapters that have already been linked in Rachel’s comments: Charlene Villaseñor Black’s essay on mother of pearl inlay; Jody Blanco’s chapter on the permutations of the story of Buddha, through Spanish theater and eventually to the Philippines; Elisabetta Corsi’s chapter on the blending of Chinese and Christian art under the Jesuits. Perhaps this is an important element that could be brought to bear on the present: the extent to which globalization creates processes that are meaningful and opaque to those of us who are accessing them from the outside. The message is that creativity is a source of political resilience. When I think of this, I immediately find parallels in such leaders as the late Marielle Franco, here in Brazil, whose unapologetic creativity seems to have been the source of her violent repression by state-condoned militias.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: In relation to your favorite themes, issues, etc., what needs work? What remains unsatisfactory, if anything? How? Why? What’s next?

Ivonne del Valle: In the “Afterword,” the editors mentioned that the volume was missing a more robust engagement with Asia and the Philippines. I think we all agree with this, but then again, there is only so much one can do in a volume. We hope that one of the articles (Blanco’s) gives readers a glimpse of the important—and changing—role of Asia vis-à-vis Europe and its American colonies. The growing importance of the role of China in Latin American countries makes this earlier connection all the more important, especially because now, China’s connection with ports, mining, and all kinds of industries in Latin America, is direct and doesn’t need Spain, Portugal or any other European country’s mediation.

Equally important, if not more so, is the lack of a truly non-Western point of view (we acknowledge this in the Introduction). Indigenous and African perspectives are missing, and we hope that future works will tackle this issue. Fortunately, there are now indigenous intellectuals (such as Yásnaya Aguilar and Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui) who have a robust production in which they share a contemporary indigenous perspective about colonialism and globalization. In an insufficient way, but trying to mitigate this gap, we started the Introduction with the words and images of Guaman Poma, who in the early 17th century was an Andean subject well aware of the consequences of globalization. Nevertheless, full-fledged indigenous and African perspectives about globalization are missing.

Rachel Sarah O’Toole: Like Ivonne, I remember our many conversations regarding the glaring gaps in the volume. The lesson for me is how a project needs to begin with the people, the questions, and the frameworks that are central to the intellectual endeavor. As many of us know, outcomes often reflect the process. If we intended to include Indigenous intellectuals, African Diaspora political actors, queer people, or articulate a gender analysis or an intersectional approach, then we needed to have begun with these commitments. Instead, we began with a clear intention to unhinge an overly Anglo-centric approach to the Iberian early modern world. The result is a compelling argument against Eurocentric approaches to empire and an generative interdisciplinary intervention. But, to move beyond adding additional voices or diversifying perspectives, we need to start with the actors or the narrative that is Indigenous, Asian, queer, disabled, or feminine-coded.

If we conceptualize the early modern Iberian Empire from an African Diaspora perspective then our story of global trade, religious networks, and racial hierarchies would find distinct centers including Cartagena and Luanda, but also remap what constituted freedom on which seas

If we conceptualize the early modern Iberian Empire from an African Diaspora perspective then our story of global trade, religious networks, and racial hierarchies would find distinct centers including Cartagena and Luanda, but also remap what constituted freedom on which seas.[1] In a sixteenth-century Atlantic, Black vecinos and vecinas articulate as free Christians and royal subjects who created the empire through their “lived experiences of blackness.”[2] Those men and women labeled as fugitives, but who called themselves sovereign in Panama, the Pacific coast, northern Brazil, and throughout the Caribbean simultaneously sharpened and warped imperial boundaries by trading with whomever was profitable. Active within institutional Catholicism, Black diviners and spiritual leaders continued and created horizontal hierarchies, polycentric pantheons, and fluid gender expressions that defy tracking into singular institutional affiliations.[3] The goal would be additional edited volumes, textbooks, monographs, films, artwork, and documentaries that continue to correct a narrative that assumes whiteness with indigenous victimization corresponds to empire.

Anna More: I completely agree with Ivonne and Rachel and, as they state, we did discuss this gap when we were putting together the scholars that compose the volume. I think that another issue for me is the relatively small space we give to the geography of the Portuguese empire, especially to Brazil. Even so, my chapter does include Africa in a very minimal way; Bruno Feitler does as well and includes Brazil and Goa. But we barely touch on the complex interaction between Spain and Portugal nor have we included the complex interactions on the West African littoral or really grappled with the medieval roots of both African and European interactions there. We could also take note of indigenous enslavement in Brazil and its interactions with the transatlantic slave trade which have multiple consequences. Finally, we could even think about non-Iberian Europeans throughout these empires. From a Portuguese perspective, these were omnipresent in Asia, Africa and Brazil.

As we have said, it is an impossible task to include everything. But I think that being honest about what is missing points to where the field can and should go.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: Give us a summary of your three articles. If I may, in relation to Ivonne’s, since she takes into account my own book on Vasco de Quiroga [a 16th-century Mexican bishop and colonial official]. What is the general thesis? Why does Quiroga matter? You call him “New Moses” and you cite Freud.

Ivonne del Valle: In my case, and since I agree with what you said about Vasco de Quiroga’s reasoning for creating hospitals, that it was directed by an economic logic, I wanted to think about this vis-à-vis two questions. First, the undeniable and prolonged “legacy” (to give it a name) of his actions. As we know, he is still a ubiquitous name and figure in Michoacán. That is, he’s somehow regarded as the “founder” of a particular indigenous state. That’s why I introduced the idea of Moses. Yet, in spite of the fact that he attempted to help indigenous communities with his hospitals, and with the Ordenanzas governing them (his new tablets, as I call them), as you remark in your own work about him, his monastic paradigm is grounded in the distribution of labor, and schedules, the division between rural and urban work, time to pray and time to eat, and time to work, etc. With work being the most important factor. Second, the fact that the protection he offered would end up (at least in theory) transforming those entering his institutions from being P’urhépechas in danger of being slaved, to being simply poor working people, is all the more telling given the 20th-century Mexican state’s plans for indigenous people—not that far from those of Quiroga: an indigenous population comprised of more or less contented, poor peasants and artisans, living separated from the wealth they help create, but don’t enjoy. The fact that Hannah Arendt’s ideas about people without a country, and the hospitality the world can afford them, are although a lot more developed not as that different from those of Quiroga, should give us another reason to pause.

Another point I wanted to make, one from which we academics are not exempted, is the ironic twist by which in deeply unequal situations, what the same entity (the colonial state in this case) does with one hand (the conquerors producing terror and havoc), it tries to fix with the other one (Vasco de Quiroga’s hospitals, for example).

Rachel Sarah O’Toole: As I explore in my chapter, “Household Challenges: The Laws of Slaveholding and the Practices of Freedom in Colonial Peru,” I invite historians of Latin America, the Atlantic world, and slavery to understand the transition from slavery to freedom as an incomplete commercial transaction. While scholars of slavery in Latin America have explored legal struggles for freedom or armed rebellion and revolution towards freedom, I suggest that manumission, or individual self-purchase was “contained within personal relationships” (164). As a result, early modern freedom was tangled into ties of economic and gendered exchanges, often within households, as men and women of the African Diaspora in colonial Peru wrestled domestic arrangements into public arenas to gain freedom.

Anna More: My chapter in this volume is a very preliminary take on the subject of my book in progress. My book charts the way that the transatlantic slave trade impacted economic theory and practice from roughly the late sixteenth through the end of the seventeenth centuries as seen through documents from Africa, the Iberian peninsula and the Americas. I think that the node for me in that chapter is the astounding inclusion in a seventeenth-century published work of a debate on the slave trade that was internal to the Jesuit order. Whereas the author of the treatise, Alonso de Sandoval, has often been seen as critical of the transatlantic slave trade, I interpret his inclusion of a superior’s justification of the slave trade in his work as a way of giving priority to the official Jesuit stance, which fell on the side of a pragmatic pro-slave trade (in fact, as the superior says, the Jesuits themselves were involved in the trade and were prolific slave owners). That is, it was actually calculated to shut down debate on the issue in a kind of “final word” manner.

The bigger issue for me in the chapter is the question of how globalization can cut both ways and potentially lead to alliances or critical perspectives from comparative or networked perspectives.

The bigger issue for me in the chapter is the question of how globalization can cut both ways and potentially lead to alliances or critical perspectives from comparative or networked perspectives. The Jesuit order was perhaps the most global of the missionary orders and certainly the most structurally global. There was potential, in this sense, that the order serve as a point of critique as their members were stationed at all points along the transatlantic slave trade. That the order shut down its internal critique can perhaps tell us something about the interests, financial and ideological, needed to sustain global institutions and the compromises that result from pragmatism.

This means that we need to think about critique as situated more locally, perhaps, and certainly understand the way that the archive becomes truncated as those that are voicing critique and dissent are actively suppressed. While I did not include this in the chapter, as I have moved forward on the topic I have found other examples of stronger Jesuit dissent. Beyond Sandoval, there were other Jesuits who were more strident and disturbed by the slave trade and the order’s involvement. But the order was fairly ruthless in snuffing out this dissent. While Sandoval’s compromise perhaps was what allowed him to publish, two Bahian Jesuits from the late sixteenth century (Miguel García and Gonçalo Leite) were forced to return home and fall out of the record.

For me these examples do not lead to the conclusion that it is impossible to effect dissent from global institutions. Rather, I believe that it points to where the creative political work needs to happen, especially now that social media has potential for activist connections that reinforce local forms of critique. And of course, we can look for early modern versions of this, albeit probably on a very different scale (such as fugitive communities; heterodox practices etc). Rachel’s answer gives marvelous examples of these.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: This handsome volume is something like a network, a hub, a web, a node. In fact, the collection Hispanic Issues does not publish single-authored works. There are three editors, ten voices in total, multiple localities, one prominent country (the U. S.) and several others–Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, a bunch of institutions, two of you are based in California, one in Brazil . . . . What can you say about this scholarly type of international enterprise? Virtues? Vices?

Ivonne del Valle: I do like this question because it gives me an opportunity to thank the editors of Hispanic Issues. Among the volumes they publish, there are several which have been key for my own development. In that way, it is a real pleasure to now have our own edited collection becoming part of an important corpus of articles that for some time now have seriously tried to understand and throw light on the colonial and Iberian experience.

We hope that some of the voices we have included help attenuate one of the vices that are more prevalent in international enterprises. That of giving priority to U. S. themes and names, interests. The virtues lie in not pretending to have the last word and/or the final word, but to allow for perspectives to interact with each other and to show the different bibliographic and institutional context in which works can be produced.

Anna More: As Ivonne states, we are very pleased and honored to be a part of the Hispanic Issues series. In terms of the diversity of our collaboration, I think that we have outlined in our previous answers how deliberate that was. It is important to underscore that again because it points to why it doesn’t happen more often. To bring scholars together, you need a place, funds, networks, and a lingua franca. It is not that this is not happening at all. In fact, we have mentioned the importance of the Tepoztlán Institute in which all three of us, and some of our contributors, participate. But in terms of publication, there are additional challenges, such as paying for translators (and here we benefited from grants from UC Berkeley and UC Irvine) and finding a way to parlay the collection into more lasting dialogues. Just as an example of the difficulty of the latter, we have yet to organize a book launch in part because of the dispersed geography and realities of our contributors during these pandemic years. And finally, of course, we should point out the obvious: this publication is in English and not the home languages of our contributors. It is most likely that the collection will circulate in North America and Europe and not in Latin America.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: Coming out of this work, where are you at this moment in terms of pedagogy and scholarship? Where are you going? How does any of this Early Modern / colonial Iberian world register in your specific localities?

Ivonne del Valle: Personally, even though I’m increasingly interested in the 20th and 21st centuries, I continue working on the Early modern/colonial period. Obviously, I think the years I’ve worked on earlier materials have helped me to be better prepared to approach later works.

As for my specific locality, and given that I already mentioned something about California and students in California, allow me to say something about Mexico (where I’m currently located) to say that Pablo González Casanova’s work on internal colonialism remains an important provocation, and that in spite of some institutions’ attempts at silencing this and its related problems (racism, for example)—I think on the proliferation of the concept of Viceroyalty and not colony in Mexico, for example—there’s a growing awareness among the younger generations of the colonial continuities that keep informing modern nation states.

Rachel Sarah O’Toole: My chapter foregrounds my second book project, “Contracting Freedom in Colonial Peru” that challenges historians and scholars of the African Diaspora to define freedom as a negotiation within patronage, rather than a legal declaration of citizenship, or manumission. By weaving together fragments of life stories, “Contracting Freedom” illuminates how enslaved women and men in the northern Peruvian city of Trujillo contested enslavers’ legal control and constructed freedom by investing in their children, their kin, and their communities. In many ways, I carefully track how enslaved and free people exercised incredible legal consciousness such as documented by Herman Bennett, Michelle McKinley, and Rebecca Scott. My goal, however, is to demonstrate that enslaved and freed people did not necessarily equate freedom with securing a legal document of manumission or petitioning slaveholders for the right to purchase themselves. Moreover, enslaved and free people were highly versed in the inadequacies of legal processes, the violence of provincial courts run by enslavers, and the sheer refusal of the colonial archive.

I chart my growing suspicion and perhaps outright disrespect of the Iberian empire and its institutions with my urge to travel intellectually beyond the realms of the early modern (as Ivonne reflects). Thanks to the events sponsored by and rare conversations with colleagues, graduate students, and undergraduate students at the University of California, Irvine, I have been heavily influenced by prison abolitionists, Black Lives Matter activists, and radical scholars who question the benefits of the liberal university. Without implicating those who inspire me including Aisha Finch (now at Emory University), Sara Johnson, and Robin Derby, I have been asking, why would I continue to follow the imperial narratives of Iberian globalization or concern myself with positivist requirements of proof?

Anna More: As I stated above, my current project is heavily focused on 16th- and 17th-century Africa and employs documents and writings in Portuguese, for the most part. I also am working slowly on a rather more whimsical project that links Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the late seventeenth-century Mexican poet and nun, to the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza and the politics of Nzinga Mbande in Angola during the same time. Both projects have benefited from our insistence on globalization, in the sense that it has given me language to defend what I am doing in ways that go beyond North American disciplinary structures. For instance, African materials have only just begun to be interpreted from literary studies; and even in history, there is a certain balkanized tradition (that as a scholar coming from the outside and with a different disciplinary base, I can happily ignore). That said, one of the most rewarding aspects of my current work is learning from the incredible scholarship that has been done by historians of early modern Africa (pre-colonial, in the African Studies language). I feel that one of my tasks as a scholar is to be sure that I have read deeply enough that I can speak to various scholarly publics, even if I am doing something slightly outside of their disciplinary traditions.

In terms of a home for this scholarship, I confess that it is getting harder to shoehorn it into the Latin American umbrella. I presented at the African Studies Association conference this year and that was a terrific experience. I have also presented at the American Historical Association as well, and it is possible to contemplate presenting at the MLA as it begins to push some of the disciplinary traditions that have kept us focused on the Americas and documents in Spanish. The Renaissance Studies Association is another possible arena, as it has become deliberate in its attempt to move beyond a European focus. And of course, I continue to attend the Tepoztlán Institute almost yearly. Although the last does not have an Early Modern focus, there are a number of us who work in the colonial period and attend regularly.

One of the biggest challenges I’ve faced is finding venues and networks in Brazil. I am talking with a colleague from Rio about starting a working group on Early Modern Studies because there are no spaces for Early Modern discussions here outside of history departments. And Brazilian academia tends to be very disciplinary so it is harder to find bridges between literary and historical studies. There is a lot of institutional investment in “methodology” as a means to distinguish and defend disciplines, even for funding and other resources. So, opening to different methodologies, or mixing, say literary reading with historical discussions is actively discouraged and even treated with suspicion or accused of undermining the discipline. This was a surprise to me when I arrived, but it just shows how funding and institutions can determine so much and, of course, create scholarly isolation or marginalization. And then there is the uniquely Brazilian problem in literary studies that one of the most important scholars of literary history, Antonio Candido, excluded the colonial period from Brazilian literary history! For all these reasons, I have found it easier to engage in more transhistorical theoretical discussions in Brazil, to use my teaching and dialogues with colleagues to ground my politics, and to continue to bring my research to more North American conferences and spaces. Meanwhile, I do hope eventually to carve out a space for dialogue in Brazil by linking scholars who are doing similar work.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: Anything else you might want to add?

Ivonne del Valle: Thanks!

Rachel Sarah O’Toole: Thank you, Fernando, for the welcomed chance to write and to think with Ivonne and Anna again! I credit both of them with the much more formal way that I approach collaborative projects as well as my own renewed fascination with how texts work.

Anna More: Fernando, it is gratifying to know that our volume has provoked such interesting questions. I have found it very illuminating to think through these issues with some distance. We hope that the volume and continued discussion will lead to new and fascinating avenues in our field, indeed that our “field” be transformed and enriched by new theoretical dialogues and comparative connections.

[1] Tamara Walker, “‘They Proved to Be Very Good Sailors’: Slavery and Freedom in the South Sea,” The Americas 78:3 (2021).

[2] Chloe Ireton, “‘They Are Blacks of the Caste of Black Christians’: Old Christian Black Blood in the Sixteenth- and Early Seventeenth-Century Iberian Atlantic,” Hispanic American Historical Review 97:4 (2017), 608; David Wheat, Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570-1640. Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2016, 146.

[3] Pablo Gómez, The Experiential Caribbean: Creating Knowledge and Healing in the Early Modern Atlantic. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017, 192.

Fernando Gomez Herrero (Spain, US; PhD (Duke University), MA (Duke U, Wake Forest U, U of Salamanca), B.A. (U of Salamanca). He has taught at Duke, Stanford, Pittsburgh, Hofstra U, Oberlin College, etc. Relocated in the U.K, he has taught at the University of Birmingham and the University of Manchester in the last four years. His book Good Places and Non-Places in Colonial Mexico: The Figure of Vasco de Quiroga (University Press of America, 2001). He is working on a volume tentatively titled The Hispanic Misnomer in the Anglo Zone: Public Conversations (2001-2022). Latest publications include: “The Latest American Appropriation of Western Universalism: A Critique of G. John Ikenberry’s ‘Liberal International Order,’” included in Rethinking Sovereignty and Territoriality in the 21st Century (http://journal.thenewpolis.com/archives/1.1/index.html ; Inaugural Issue, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Winter 2022), Decoloniality and the Disintegration of Western Cognitive Empire: 90 pages.site: https://www.fernandogherrero.com. He has recently collaborated with the Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia covering international news, particularly U.S. and U.K. (https://www.lavanguardia.com/autores/fernando-gomez.html , in Spanish).