This November, UT Austin will host a workshop on the Entangled Histories of the Early Modern British and Iberian Empire and their Successor Republics, bringing together graduate students and faculty from across the United States. The emphasis of this event is to explore the ways in which ideas, commodities, and peoples circulated across the formal boundaries of empires and nations. In the lead up to the workshop Not Even Past will be publishing reviews of key works of scholarship in the area of entangled history during the following month. These reviews are written by UT graduate students, many of whom will be submitting papers to the workshop, and will lay the foundation for the lively conversations this November. To kick-off, UT graduate student Bradley Dixon introduces the key questions that will be addressed at the workshop, and proposes a new model for studying entanglement.

When William Strachey imagined Virginia’s future, he pictured Peru.

In 1612, the colony’s former secretary compared the Powhatan Indians of Virginia with the “Cassiques or Comaunders of Indian Townes in Peru” whose people mined the silver that was filling Spain’s coffers. The caciques, Strachey wrote, were “rich in their furniture horses and Cattell.” Their wealth, however, was not only in material goods but in political capital—namely, the protection they received as vassals to the king of Spain. In the same way, Strachey pictured Virginia’s Indians becoming vassals to England’s “king James, who will give them Justice and defend them against their enemyes.”

This passage poses a number of interesting questions. How could a Protestant Englishman like Strachey look to Catholic Spain as a model for ruling indigenous peoples? Where did he obtain his information about the nature of the Spanish Empire? And, perhaps most importantly, how does the fact that Strachey imagined Virginia as a Protestant Peru affect our understanding of the colonial venture that started in Jamestown?

This November, a conference of UT history graduate students and faculty drawn from near and far will consider these and other questions as they ponder the “entanglement” of the Spanish and British empires in the Atlantic world. Three scholars among the presenters—Eliga Gould, Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, and Benjamin Breen—have already published work that complicates, opens, or even erases, the historiographical barrier that often stands between the British and Iberian Atlantics. Instead, they have emphasized the peoples, goods, and influences that crossed imperial boundaries. The Spanish empire, which throughout the colonial era was the older, larger, and richer of the two, exuded a powerful influence and served as a potent example for subsequent colonization enterprises by other European nations, notably Britain.

For Gould, the most important unit of analysis remains “empire.” Gould might explain William Strachey’s vision as a logical in a period in which Spain’s empire was not just preeminent but dominant. When Strachey wrote, Jamestown was a tiny, hardscrabble outpost within what Gould has called “a Spanish periphery that included much of the Western Hemisphere.” Seen from this perspective, one might picture the two empires as partners in a dance, each watching the other, anticipating the other’s moves. Gould argues that the mutual influences of the two empires reached to their very cores. The encounters between the partner-empires happened in locales far and wide, not just on their outer borders.

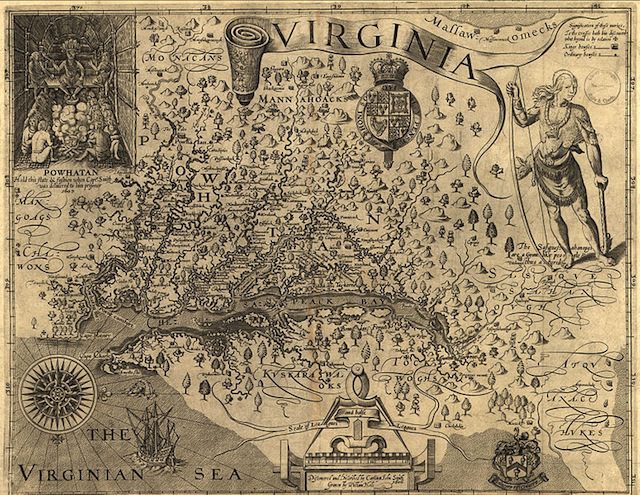

![Description des Indes Occidentales [Description of the West Indies]. Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. Amsterdam: M. Colin, 1622. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)](http://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/tordes.jpg)

Cañizares-Esguerra and Breen proposed, as an alternative model, a “hybrid Atlantic” that de-centers both the nation-state and the empire as the major units of analysis. More important to the development of the hybrid Atlantic are the “local contingencies, cultural exchanges, extra-national groups, indigenous perspectives, and the roles of nonhuman actors like objects, environments, and ecologies.” The political map of this hybrid Atlantic would have little in common with traditional maps of European imperial influence. The hybrid Atlantic model recognizes the many places that “were only nominally controlled by any European state in the colonial era.”

If Gould’s model of entanglement is the dance of empires, then Cañizares-Esguerra’s and Breen’s seems more like an elaborate pinball game that Jorge Luis Borges might have imagined. The machine encompasses the entire Atlantic world with, not multiple, but millions of balls in play, careening into each other and transforming the bumpers and flippers themselves as they collide with them.

More than a decade ago, Daniel K. Richter turned the perspective of early North America around in another way, recounting the history of colonization from the American Indian’s point of view. “Facing East from Indian Country,” the title of his now-classic book, has become a shorthand for placing the views of Native Americans at the heart of North American history.

So, what if, as a thought experiment, we faced northwards from the Andes? Seen from Peru, both Virginia and New England look very different from the image that most people in the United States learned in school, in which these tiny settlements are the original acorns from which mighty oaks would one day grow.

Viewed from the Andes, Virginia was but a small outpost—and a trespass—in La Florida, a region where Spanish missions were already fifty years old and where Native American polities were independent and sovereign. Likewise, when seen in this way, familiar figures appear in a different guise. John Smith becomes a would-be conquistador, striving to subdue the peoples of the Chesapeake. Captain Christopher Newport, like a latter day Cortes or Pizarro, sought to crown—and thus make a vassal of—a Native emperor, Powhatan. The colonial world that emerged in the Chesapeake would be different but its differences must have seemed like matters of scale at the beginning.

From the Andes, the settlements of the British Empire probably always seemed smaller. That is, until it wasn’t small anymore and was barking at the gates of the Spanish empire. But even then, both empires watched each other carefully for weaknesses and for ideas.

This southern perspective offers only one way that we might begin to perceive and conceive of the “entanglements” between the British and Spanish Americas. As the conference gathers in November, we look forward to exploring others.

You may also like:

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott

Christina Marie Villarreal recommends Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (University of Chicago Press, 2012) by Daniela Bleichmar

Sources:

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra and Benjamin Breen, “Hybrid Atlantics: Future Directions for the History of the Atlantic World,” History Compass 11/8 (2013)

Eliga H. Gould, “Entangled Histories, Entangled Worlds: The English-Speaking Atlantic as a Spanish Periphery,” American Historical Review 112, no. 3 (Jun., 2007).

Daniel K. Richter, Facing East from Indian Country: a Native History of Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003)

William Strachey, “The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania,” in Captain John Smith: Writings and Other Narratives of Roanoke, Jamestown, and the First English Settlement of America, ed. James Horn (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2007).