Good historians keep an open mind when doing archival research. Our reading of the relevant literature, not to mention the preliminary research we conduct, provides a general understanding of our topic, but we have to prepare ourselves for surprises. This is the most exciting part of research — examining documents no one has seen and making connections others have not made. Research has a funny way of bringing the unforeseeable into one’s life, though.

There was little reason I should have anticipated coming across Hitler in my research. I am a historian of the United States and my dissertation examines the history of sexual orientation change therapies from the Second World War into the twenty-first century. A wide-range of stakeholders have practiced, sought out, been forced to undergo, and challenged the ethics of therapeutic practices aimed at changing a person’s homosexuality. Needless to say, researching this topic has brought me into contact with some disturbing history. This has included graphic descriptions of men and women being electrocuted or even lobotomized because of their sexual orientation. I expected to come across these accounts in the archives. They are an integral part of the history I want to tell. Hitler was a different story.

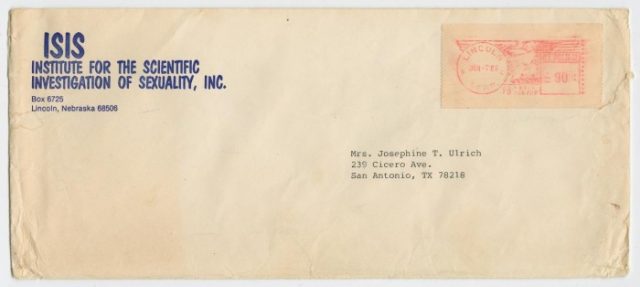

I first came across the infamous German dictator while conducting research in the Special Collections at the University of North Texas. I was going through an extensive LGBT collection and came to a folder devoted to Paul Cameron. In the 1980s, Cameron earned acclaim for being expelled from the American Psychological Association (APA). The reason? He falsified data in order to push an anti-gay agenda. After being expelled from the APA, Cameron doubled his efforts to discredit LGBT activists by continuing to conduct and disseminate research. This included a 1985 pamphlet called “Criminality, Social Disruption and Homosexuality: Homosexuality is a Crime against Humanity.” Cameron’s organization, the Institute for the Scientific Investigation of Sexuality (yes, they were called ISIS), mailed thousands of these pamphlets across the nation.

Envelope from a promotional Institute for the Scientific Investigation of Sexuality mailing (via UNT Digital Library).

In “Criminality, Social Disruption and Homosexuality,” ISIS included a section with the title “German History Repeats Itself in the U.S.” According to the pamphlet, “gays [in 1920s and 1930s Germany] were seeking a political party to carry their lifestyle to power. They threw their weight behind the Nazis and were rewarded with leadership of the stormtroopers (SA).” The pamphlet continues: “Over time, Nazi youth organizations and camps became notorious for homosexual molestations. Open homosexuality, pornography, drugs and prostitution turned Berlin into the San Francisco of Europe.”

I had no clue what to think when I first read these sentences. Did I not pay attention in my world history courses? Were my teachers and professors woefully ignorant of the past? I sent pictures of the pamphlet to colleagues who know German history much better than I do. We were all confused. Despite this confusion, I knew that I would not be free from Hitler.

I was proven correct repeatedly as I conducted research at the Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives in Nashville. In 1993, Cameron’s organization, now called the Family Research Institute, sent out a newsletter with an article that asked, “Was the Young Hitler a Homosexual Prostitute?” The authors pointed to Samuel Igra’s 1945 work, Germany’s National Vice, as evidence that Hitler was a homosexual artist before rising to power. Other publications, including Scott Lively and Kevin Abrams’ The Pink Swastika: Homosexuality in the Nazi Party (1995), give the same warning: the Nazis were a bunch of homosexuals who desired a fascistic takeover of their country. Importantly for my research, proponents of sexual orientation change therapies have referred to not only Cameron’s pamphlets but also the works of Igra and Lively and Abrams. If I truly want to understand the intellectual rationale for sexual orientation change therapies, I had to know how and why someone would want to believe that the Nazis were a bunch of homosexuals. But first, I needed to see if there was any historical basis for these accusations.

Research into the history of Nazism brought me to Ernst Röhm, the head of the SA. Röhm, who had convinced Hitler of his political potential in 1919, was homosexual, a fact that Hitler knew about his political and military subordinate. Over the next fifteen years, Hitler and Röhm worked closely as they grew the Nazi Party. Although Röhm and a few other SA leaders were open about their homosexuality, their rise to power was not due to their sexual orientation. What’s more clear, however, is that the downfall of Röhm and the SA prefaced the Nazi persecution of homosexuals. In 1934, Hitler, with the help of other aides (like Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels, and Heinrich Himmler), orchestrated the arrest of Röhm and other SA leaders because the latter challenged Hitler’s authority. After Röhm was murdered in his prison cell (Hitler gave him the option of taking his own life, which he refused to do), homosexuals became a group targeted by the Nazis. A pink triangle, not a pink swastika, soon singled out (mostly) homosexual males in concentration camps.

Although I was not prepared to find Hitler in the archives, it is clear that people like Cameron had easy-to-discern motivations. They were able to use parts of the past, even if they took liberties with what had happened, to discredit LGBT activists and claims for equality. What better way to do this than compare them to the Nazis?

![]()

More by Christopher Babits on Not Even Past:

Another Perspective on the Texas Textbook Controversy

Review of The Rise of Liberal Religion, by Matthew Hedstrom (2013)

The Blemished Archive: How Documents Get Saved

![]()