This article originally appeared in The Atlantic on September 17, 2016.

Thousands of Native American protesters are currently fighting against the proposed construction of the Dakota Access pipeline in North Dakota. They are doing more than just trying to protect their land. They are fighting for their culture—and, as the Ojibwe activist Winona LaDuke argues, their future. Advances on Indian lands have always been, and continue to be, attacks on indigenous values. Non-tribal governments and corporations with interests in tribal land have not slowed such attacks in recent years, but members of indigenous communities throughout the United States have rallied new resistance. Some, like the Standing Rock Sioux in North Dakota, are challenging corporate incursions on their treaty lands and water. Others are fighting something slightly more subtle: renewed calls to change the ownership structure of Native lands.

Rally against the Dakota Access Pipeline in September 2016 (via Fibonacci Blue).

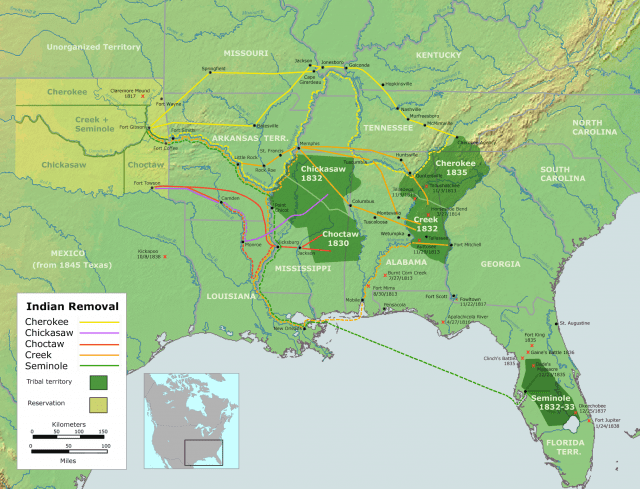

Conflicts over the use and ownership of Native lands are not new. Land has been at the center of virtually every significant interaction between Natives and non-Natives since the earliest days of European contact with the indigenous peoples of North America. By the 19th century, federal Indian land policies divided communal lands among individual tribal members in a proposed attempt to make them into farmers. The result instead was that struggling tribes were further dispossessed of their land. In recent decades, tribes, corporations, and the federal government have fought over control of Native land and resources in contentious protests and legal actions, including the Oak Flat, the San Francisco Peaks Controversy, and the Keystone XL pipeline.

For most Americans, land is money, and land ownership constitutes power. For individuals who are not familiar with tribal cultures and histories, it is easy to assume that the ability to make money off of land by leasing it to extractive industries or selling it off is a natural path to personal success and therefore prosperity for the community at large. Make no mistake: For Native people, a link exists between landownership and success, but it is much more complex and intimate than the personal ability to exploit or sell land for financial gain. Not all communities are facing the same kind of crises, but almost all recognize the importance of land to cultural preservation. Whether in our ancestral homelands, such as those where the Lakota have stopped the construction of the pipeline, or in areas of Oklahoma, where more than two dozen tribes were forcefully placed during the 19th century, protecting our tribal land bases is an intrinsic part of the formula that will lead to greater prosperity and success for individuals and tribes in Indian country.

That is the reason why protests to defend treaty-protected lands, like the current protests over the Dakota Access pipeline, are so important. It is also the reason why thousands of Native people, representing scores of tribes, have made the journey to North Dakota to protest the pipeline that threatens both sites that are sacred to the Sioux people and the drinking water for those living on the nearby reservation. They are there to speak for their ancestors who are buried on those sites. They are there to speak for themselves and their right to preserve their ceremonial sites and drinking water. And they are there to speak for the subsequent generations who will have to live with the results of the pipeline’s construction.

Proponents of privatization, be they corporations or well-intentioned free-market reformers, are disregarding Indian culture and values. The author Naomi Schaefer Riley, for instance, recently published an article in The Atlantic suggesting that Native American communities suffer from economic devastation and social inequity due to the federal policy of holding Native American lands in trust. Her solution to this policy, which she argues has stymied individual success and contributed to endemic poverty in Native American communities, is the resurrection of a much older, failed solution: the redistribution of lands collectively held by tribes to individuals.

Pine Ridge Reservation, one of the North Dakota reservations threatened by the Dakota Access Pipeline (via Wikimedia Commons).

Reform-minded authors like Schaefer Riley begin making their case by citing a number of terrifying statistics about poverty on reservations, violence against Native women, and teen suicide rates, among others. All are largely factual. Schaefer Riley’s solution, however, creates a false dichotomy, suggesting that success is limited to either the individual or the tribe. She claims that tribal citizens’ inability to privately own, and therefore capitalize on, tribal lands, “prevents American Indians from reaping numerous benefits.” This is a narrow interpretation of the resources and policies that would benefit Natives, and it disregards the cultural and spiritual values at the core of Native American tribal societies.

This frame of reference also fails to acknowledge that Native communities face the arduous task of overcoming these social challenges as a direct result of centuries of federal policies that disassembled traditional social structures, moved entire communities, and attempted to dismantle tribal sovereignty. Virtually every one of those policies had an end goal of eliminating tribal rights to land and advanced a non-Native understanding of how to properly “use” land.

While Schaefer Riley is correct that social problems persist on some reservations, she neglects to consider that since the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 and the Tribal Self-Governance Act of 1994, hundreds of tribes have consistently shown improvement when allowed to manage their own affairs. Self-governance means that tribal governments decide where and how to allocate resources for certain programs, such as health care via funding from the Indian Health Service, to meet the needs of their community. Although more needs to be done, the solution proposed by Schaefer Riley would constitute an assault on tribal lands, not a path to prosperity.

Native Americans flee from the allegorical representation of Manifest Destiny in this 1872 painting by John Gast (via Wikimedia Commons).

On reservation lands, a tribe decides what type of infrastructure its community needs; this can include health clinics, schools, housing for low income families and elders, cultural centers, and a wide range of enterprises. My own tribe, the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, is the largest employer in Pottawatomie County, a relatively rural area of central Oklahoma. We provide jobs to more than 2,400 people, Natives and non-Natives, in our government administration offices and more than 20 businesses. This is only possible because we have tribally owned land on which to develop and operate enterprises. Across Indian Country, tribes are often one of the few sources of jobs in areas far from urban centers, and they are increasingly at the forefront of industries like tourism and green energy.

Tribes should also be able to determine what constitutes success for themselves, and have recently done so by pursuing policy initiatives that recognize tribal sovereignty on their land, not by focusing on private property rights that would break it apart. In 2012 Congress passed a critical piece of legislation that provides tribes an avenue to greater sovereignty and will lead to more investment and economic development in Indian country. The Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Homeownership (HEARTH) Act gives participating tribes the authority to lease reservation, or trust land, for residential or business purposes without further approval by the federal government. This advancement in self-governance means that tribes are able to determine the housing or commercial projects that are the most needed in their communities and the best way to utilize their land base. It also means they have more direct control of tribal assets, which makes them better able to shape their own future. Unlike land privatization, the HEARTH Act keeps the tribally owned trust or reservation land intact, and therefore does not negate the federal government’s trust responsibilities for those properties.

Two women from the Idle No More movement, an indigenous rights alliance in Canada (via Wikimedia Commons).

Beyond such policies, efforts to help Native Americans gain socio-economic success should start by looking at what holds specific tribes back from taking advantage of avenues for more self-governance and economic development. Some tribes face daunting challenges that present a barrier to pursuing economic development projects. Instead, they are combating life-threatening social and emotional upheaval rooted in cultural loss as a result of wars, genocide, forced removals, separation from ancestral homelands, children taken away to boarding schools, and other experiences that negatively impacted tribal communities across generations. Brutal federal policies that focused on assimilation pushed Native people to accept a narrow concept of what it means to be a successful American. Recovering, preserving, and teaching Native cultural traditions gives community members direction, purpose, and a sense of identity. It also instills generational wisdom, encourages respect for elders, and reinforces familial responsibilities. Only when a tribe restores its cultural riches can it turn its attention to financial gains.

There are ways to address economic and social challenges for Native Americans within a tribal system that don’t undermine the fundamental nature of the tribe or destroy the land base necessary to create a strong and thriving community. Native people across the country are steadily making strides toward that goal, and their successes are a testament to the courage and resilience of their communities. We will heal our broken communities from the ground up, not by selling or exploiting the ground beneath our feet.

![]()

You may also like:

Not Even Past contributors survey The American West, Native Americans, and Environmental History.

Nakia Parker explores The First Texans: An Exhibit in Jester Hall.

Caroline Murray discusses Mapping Indigenous Los Angeles: A Public History Project.

![]()