From the Editors: From There to Here document the journeys taken by individual graduate students to Garrison hall and the University of Texas at Austin. Gabrielle Esparza, who is completing her PhD in History, shares her story with us. For more about Gabrielle, see her spotlight here.

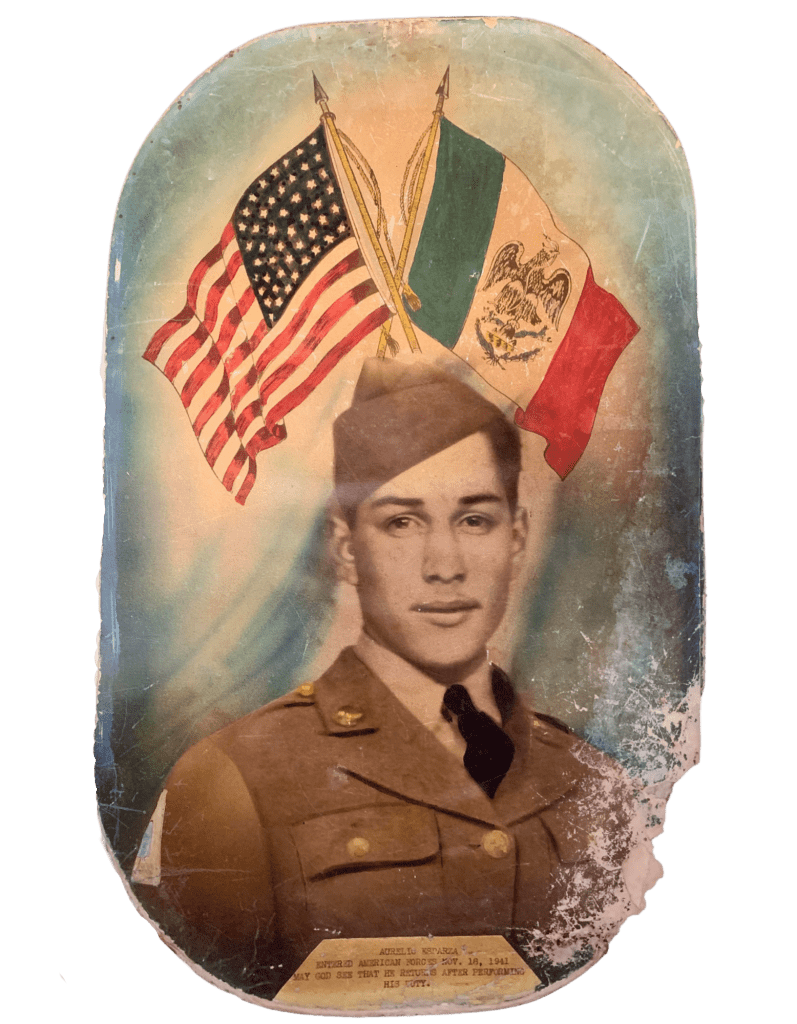

My great-grandpa Earl died when I was eight years old. I knew him as a frail old man, who sometimes called me by the wrong name. Gabriela instead of Gabrielle. At his funeral, I met a much younger version of my great-grandpa through the stories and photographs my relatives shared. The old pictures fascinated me. I fixated on a photo of him in his army uniform, which displayed the U.S. and Mexican flags behind him. Below his portrait, the caption read: “Aurelio Esparza. Entered American Forces Nov. 18, 1941. May God see that he returns after performing his duty.”

I had never heard the name Aurelio before. I had only known Earl. A name that my father and grandfather both carried in his honor. I asked why my great-grandpa changed his name from Aurelio. My dad joked, “Aurelio sounded a lot like unemployed.” A comment I would not fully grasp for a few more years.

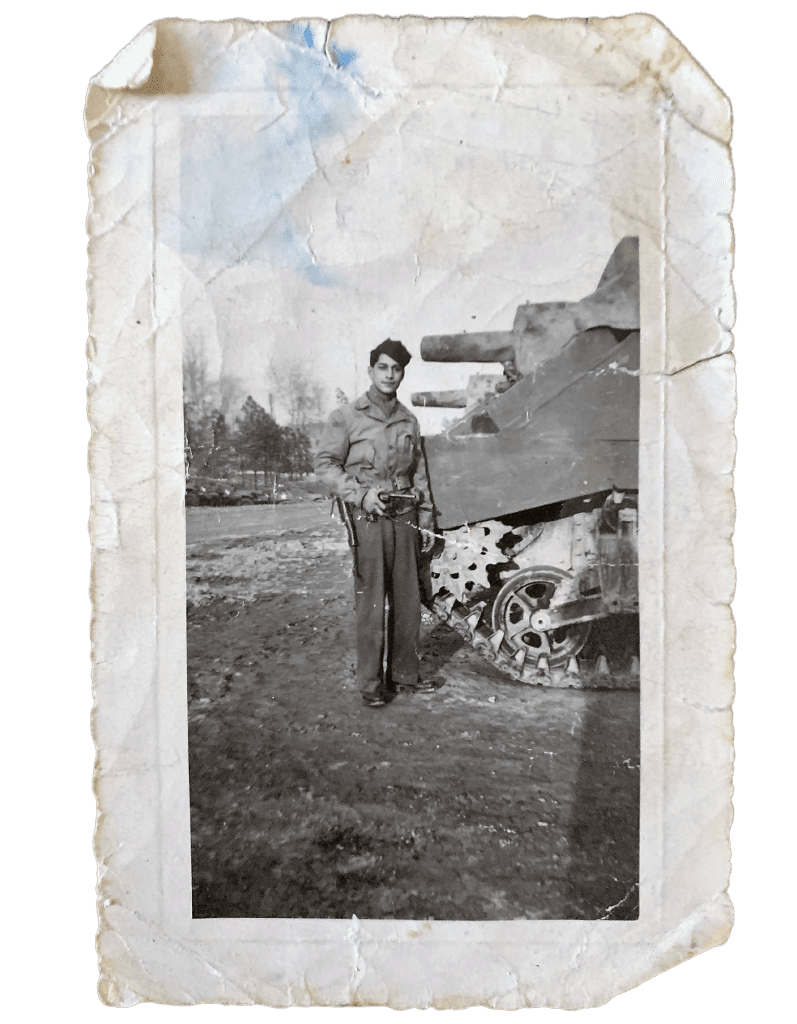

Nobody offered many details about his original name. My great-grandma Shirley—his wife—may have been the only one who could answer my questions, but she fell ill on the morning of his funeral. Shirley never recovered and died only a month after Earl. I figured I would never know why he changed his name and how he settled on Earl, so I dropped my fixation on “Aurelio” and focused on Earl’s military service. My grandpa Mick (he never went by his given name of Earl) shared that his dad rarely talked about the war, but he offered me specifics about where Earl was stationed and in which unit he served. This led me to school projects on the Normandy Campaign and General Patton. I tried to imagine what my great-grandpa had experienced but also began to recognize these years as just one brief part of his life.

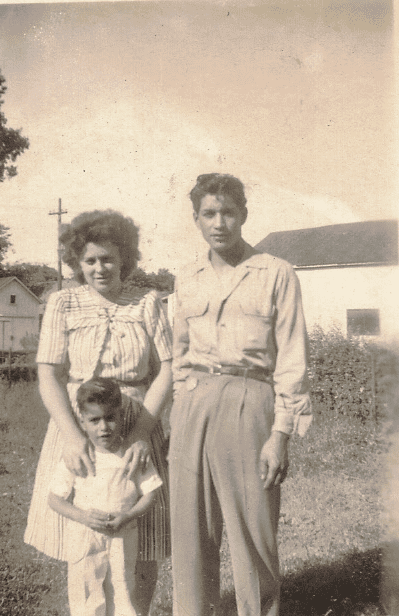

My focus shifted to understanding who Earl was before and after the war. Following his military service, he moved to Illinois to work at the International Harvester Farmall Plant in the Rock Island. His wife Shirley got a job there during the war. Earl and Shirley had met in North Dakota in the late 1930s. Her family farmed in Grafton, and Earl traveled there from Texas as a migrant farmworker each year.

By 1942, Earl and Shirley had three children. They welcomed four more after settling in Illinois. Their kids, including my grandpa, never learned Spanish although Earl spoke it with his extended family. As a child, I wondered why my great-grandpa anglicized his name and neglected to teach his children Spanish.

As I got older, I felt a sense of shame about my inability to speak the language. Our last name always drew questions about my identity. These were often followed by questions about whether I understood or spoke Spanish. I dreaded admitting that I only knew a few words, and I wished my great-grandpa had shared the language with his children and grandchildren. But I also came to understand that he had given up aspects of his culture to build a life in the U.S.

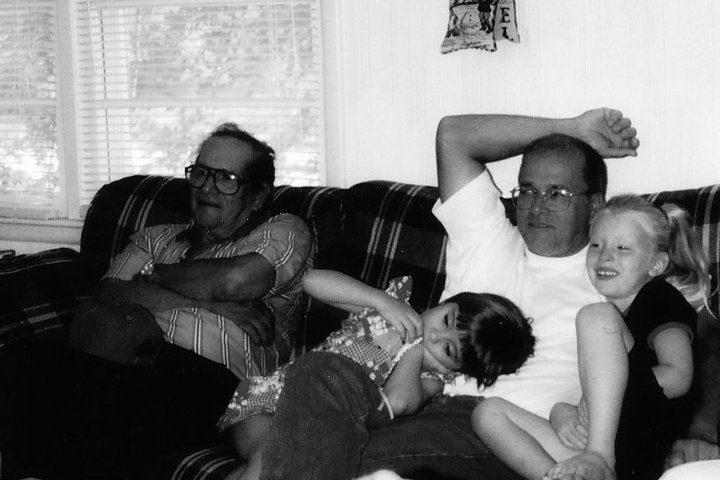

This loss shaped my academic path. I trace my decision to study history and language to my great-grandpa. In college, I double majored in history and Spanish. Determined to learn the language my family had lost, I studied abroad and then applied for a Fulbright fellowship to Argentina. The fellowship seemed like magical thinking, but somehow, I won it. Before sharing the news with anyone else, I called my grandpa Mick. I remember him saying, “I wish my dad were still here. He would be so proud.” I had never shared with my grandpa Mick that my interest in history, the Spanish language, and Latin America stemmed from his father, my great-grandpa. Yet, he seemed to instinctively understand and always supported my ambitions. He drove me to college visits, helped me figure out finances, and bought my textbooks every semester. I would not have pursued history without my great-grandpa, but I would not be a historian without my grandpa.

Gabrielle Esparza is a Ph.D. candidate in Latin American history, with a focus on twentieth-century Argentina. Her research interests include democratization, transitional justice, and human rights. She holds a B.A. in History and Spanish from Illinois College and received a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship to Argentina in 2017. There she taught at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Gabrielle graduated with her M.A. in History from the University of Texas at Austin in 2020. Her master’s thesis The Politics of Human Rights Prosecutions: Civil Military Relations during the Alfonsín Presidency, 1983-1989 examines the evolution of President Raúl Alfonsín’s human rights policies from his candidacy to his presidency, which followed Argentina’s most repressive dictatorship. At the University of Texas at Austin, Gabrielle has served as a graduate research assistant at the Texas State Historical Association and contributed to the organization’s Handbook of Texas. She also served as co-coordinator of the Symposium on Gender, History, and Sexuality in 2020-2021 and as associate editor of Not Even Past from January 2021 to August 2022.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.