By Justin Heath

The conquest of the Americas first gained notoriety through the words of a penitent priest by the name of Bartolomé de las Casas, a compatriot of the Spanish conquerors. As a moral counterpoint to the conquistadors’ lawless expropriation, Las Casas would figure prominently in most textbook histories of the “New World.” From Boston to Buenos Aires, schoolchildren still learn of the Dominican friar’s crusade against the enslavement of indigenous peoples in the Americas. For some, Las Casas’ accolades are well-deserved. Historian Lewis Hanke, for instance, saw in Las Casas the first glimmer of modern humanitarianism, suggestive of a new multicultural awareness in the modern era. Others, such as Daniel Castro, have questioned the motivations of this early ideologue of “ecclesiastical imperialism.” Regardless of one’s opinions of the man, this preoccupation with Las Casas’ role as “advocate” for the indigenous peoples has obscured an important insight into post-conquest society: Native peoples from central Mexico to modern-day Venezuela pursued their own self-interest through legal action, even during times of personal distress and communal hardship following European encroachment.

The conquest of the Americas first gained notoriety through the words of a penitent priest by the name of Bartolomé de las Casas, a compatriot of the Spanish conquerors. As a moral counterpoint to the conquistadors’ lawless expropriation, Las Casas would figure prominently in most textbook histories of the “New World.” From Boston to Buenos Aires, schoolchildren still learn of the Dominican friar’s crusade against the enslavement of indigenous peoples in the Americas. For some, Las Casas’ accolades are well-deserved. Historian Lewis Hanke, for instance, saw in Las Casas the first glimmer of modern humanitarianism, suggestive of a new multicultural awareness in the modern era. Others, such as Daniel Castro, have questioned the motivations of this early ideologue of “ecclesiastical imperialism.” Regardless of one’s opinions of the man, this preoccupation with Las Casas’ role as “advocate” for the indigenous peoples has obscured an important insight into post-conquest society: Native peoples from central Mexico to modern-day Venezuela pursued their own self-interest through legal action, even during times of personal distress and communal hardship following European encroachment.

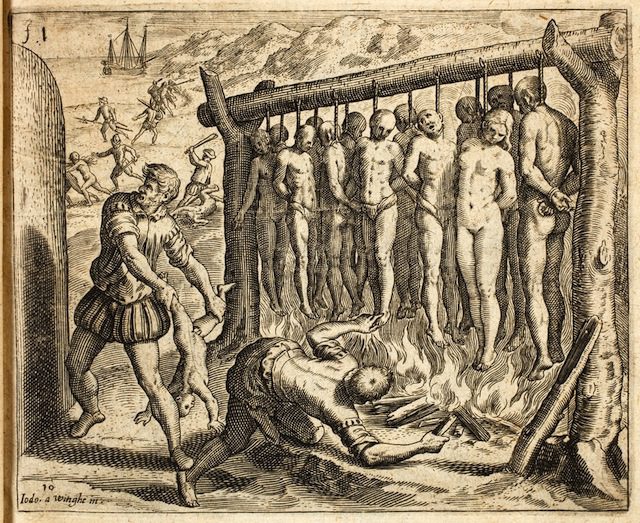

Depiction of Spanish atrocities committed in the conquest of Cuba in Las Casas’s “Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias”. The rendering was by Joos van Winghe and the Flemish Protestant artist Theodor de Bry. Via Wikipedia

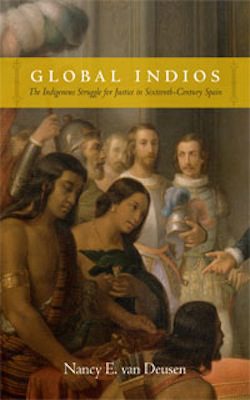

In Global Indios, Nancy Van Deusen questions many such received notions of the conquest. By following the case histories of particular indigenous slaves across the Atlantic, the author takes the reader to a less familiar venue: the courtrooms of sixteenth-century Castile. There, in the administrative heart of the Spanish Empire, the colonized peoples of the Americas would at times resist, at times accommodate, and at all times struggle over the legal parameters that shaped their everyday existence.

From the outset, the Spanish Crown had distinguished “cannibals” from “creatures of reason,” and “barbarous” from “civilized” nations. These formal distinctions, however, did not prevent slavers from abducting all sorts of people across the Americas to sell in the port cities of Spain and Portugal. Imperial laws permitted such transactions, provided that the indigenous captives hailed from the uncooperative “war zones” of the periphery. Individual slaves lucky enough to escape captivity in these port cities quickly sought protection under the auspices of the law. Catalina de Velasco, for example (an acquaintance of Las Casas), asserted her legal exemption from servitude by claiming the ethnic status of a native “Mexican” while her mistress staked a counter-claim that this young domestic servant hailed from Portuguese Brazil, a jurisdiction where no such legal safeguards applied for indigenous peoples. Global Indios focuses on similar trial proceedings, taking note of the various stakeholders, expert witnesses, and legal strategies that shaped conceptions of “indio-ness” (that is, Indian-ness or indigeneity) across the early Atlantic World.

Approaching a new set of questions, Global Indios has many surprises in store for the contemporary reader. The most prominent is the author’s concept of an “indioscape,” a cognitive mapping of the New World and its peoples. By the mid-sixteenth century, Europeans had realized that an entire landmass separated western Eurasia from East Asia. However, the mapping of this supercontinent was far from complete by that time. Relying upon the expert testimony of missionaries and those who had travelled to the New World, the courts pieced together a series of cultural habits and physical traits that roughly differentiated certain environments, regions, and peoples of the New World. In the courtrooms, judicial officials and third-party experts would interrogate litigants, while taking into account their physiognomy and entering it into the legal record.

The debate around racial status reveals just how fuzzy these distinctions were, especially during the early phases of colonialism. Establishing the identity of an “indio” often revolved around a series of guided questions and prejudicial observations that informed the European eye toward an ambiguous legal subject. This assessment may imply limited input on the part of indigenous petitioners. However, as the author shows, these litigants were not passive subjects before a foreign legal process. In spite of these hurdles, indigenous litigants formed a successful strategy over the decades. The vast majority won their cases (even if they continued to face adversity outside of the courtroom — in the back alleys, the inn rooms, or the roadways of Spain). Van Deusen’s book analyzes the forced dialogue between colonizer and colonized in the administrative heart of Europe’s first modern empire, where the plaintiffs shaped the line of inquiry. The author infers that these slaves exploited the ambiguities of indio-ness to secure legal protections for themselves and their families.

Nancy van Deusen’s study of indio-ness in the courtroom makes a substantial contribution to the ethno-historical study of slavery. More specifically, her book marks the beginning of a more ambitious perspective that pokes holes in the alleged parochialism of indigenous historical actors. One of the first studies to explore the trans-imperial construction of racial categories in the sixteenth century, Global Indios perhaps raises more questions than answers. That being said, the speculative turn in the author’s reasoning — while problematic in certain instances — also showcases the indispensable role of the imagination in re-envisioning the moral history of our own times. For this reason alone, Van Deusen’s is required reading for everyone interested in the history of racial thought.

Nancy van Deusen, Global Indios: The Indigenous Struggle for Justice in Sixteenth-Century Spain (Duke University Press, 2015)

You may also like:

Adrian Masters recommends Joanne Rappaport’s The Disappearing Mestizo: Configuring Difference in the Colonial New Kingdom of Granada (Duke University Press, 2014)

Ann Twinam discusses her work on Purchasing Whiteness in Colonial Latin America

Naming and Picturing New World Nature, by Maria Jose Afanador LLach

Kristie Flannery’s review of Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America,edited by Andrew B. Fisher and Matthew D. O’Hara (2009)

Susan Deans-Smith on the Casta Paintings