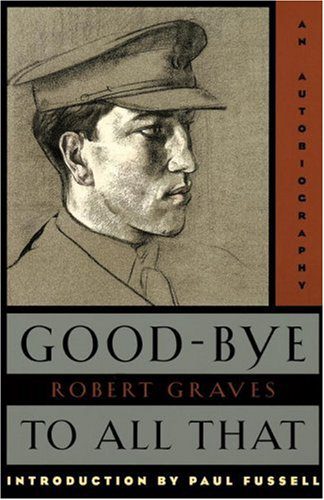

Reflecting on his motives for joining the Royal Welch Fusiliers at the outbreak of the First World War, Robert Graves wrote: “I thought that it might last just long enough to delay my going to Oxford in October, which I dreaded.” So began a five year pause in Graves’ life, in which the main action of his autobiography unfolds. In Good-Bye to All That, Graves powerfully explores the horrors of the First World War, while also providing a compelling look at the inner workings of British society.

Reflecting on his motives for joining the Royal Welch Fusiliers at the outbreak of the First World War, Robert Graves wrote: “I thought that it might last just long enough to delay my going to Oxford in October, which I dreaded.” So began a five year pause in Graves’ life, in which the main action of his autobiography unfolds. In Good-Bye to All That, Graves powerfully explores the horrors of the First World War, while also providing a compelling look at the inner workings of British society.

On the front lines at Cuinchy and Laventie, divisions between the men who fought became clear. Graves highlights the bravery of Welsh soldiers who, as former miners, prove pessimistic but particularly well-adjusted to the trenches, but he adds a Welsh comrade’s sentiments regarding Scottish battalions, noting that they, “run like hell both ways.” While stationed in Ireland near war’s end, Graves comes down with Spanish influenza and flees for London to avoid suffering treatment in a “horrific” Irish hospital. In this way, Graves also relays the prevalence of regarding class and racial divisions in imperial Britain.

Throughout, Graves drives the social analysis implicit in his work with a dark sense of humor. For instance, as though schoolboys at Charterhouse, soldiers roll a defused bomb through the trenches to play a cruel joke on a shell-shocked comrade. Graves finds himself naked in a public bath in Béthune with the Prince of Wales, who was “graciously pleased to remark how emphatically cold the water was.” In a burned-out French village, the troops organize an impromptu cricket match using a birdcage as the wicket – with the dead parrot still inside. These vivid images reveal men far from home and in close proximity to death, struggling to maintain the regular routines of English life. With his humor and gently sardonic prose, Graves’s autobiography yields a depiction of the First World War and its domestic aftermath that says as much about British society as it does about the author’s own life.

English soldiers in the trenches at Nieuport Bains, Belgium, 1917. The sergeant in the foreground is watching the German line through a periscope fixed on his bayonet. (Image courtesy of the United Kingdom Government)

English soldiers in the trenches at Nieuport Bains, Belgium, 1917. The sergeant in the foreground is watching the German line through a periscope fixed on his bayonet. (Image courtesy of the United Kingdom Government)

Following the war, Graves picked up his life almost exactly where he left it. He matriculated at Oxford and launched a long career as a writer, poet, and scholar of antiquity. Yet, like so many of Graves’s generation, the war years left psychological scars that would linger for life. Good-Bye to All That investigates those scars and gives readers a crystalline sense of the trauma that left them.

You may also like:

Jermaine Thibodeaux’s piece on African-American soldiers in WWI.