by Michelle Reeves

Henry Wallace, according to Oliver Stone’s Showtime series, Untold History of the United States, was a true American hero, a lover of peace, and a gentle soul whose leadership could have saved the world from the Cold War. While no one has ever accused Stone of historical accuracy, his past work did not lay claim to documentary status. So how well does Stone’s interpretation comport with the historical record? As Tom Devine’s new book, Henry Wallace’s 1948 Presidential Campaign and the Future of Postwar Liberalism, makes clear, Stone’s view of Wallace is deeply misleading and based on an extremely selective reading of the sources. In fact, as Devine shows, Wallace was an astoundingly naïve politician, and he has remained a fairly obscure historical figure because he did not have much to contribute to American politics, beyond a pie-in-the-sky utopianism that was completely out of sync with the realities of his era.

Henry Wallace, according to Oliver Stone’s Showtime series, Untold History of the United States, was a true American hero, a lover of peace, and a gentle soul whose leadership could have saved the world from the Cold War. While no one has ever accused Stone of historical accuracy, his past work did not lay claim to documentary status. So how well does Stone’s interpretation comport with the historical record? As Tom Devine’s new book, Henry Wallace’s 1948 Presidential Campaign and the Future of Postwar Liberalism, makes clear, Stone’s view of Wallace is deeply misleading and based on an extremely selective reading of the sources. In fact, as Devine shows, Wallace was an astoundingly naïve politician, and he has remained a fairly obscure historical figure because he did not have much to contribute to American politics, beyond a pie-in-the-sky utopianism that was completely out of sync with the realities of his era.

Though the scholarship on the Red Scare and McCarthyism is extensive, that on Popular Front liberalism is decidedly less so. The historiography of Wallace’s campaign, moreover, tends to downplay or misunderstand the role of American communists in the Progressive Party. Devine provides a timely corrective by examining the alliance between the communists and the progressive left and illuminating the destructive influence of the U.S. Communist Party. Declaring the incipient fascism of U.S. domestic policy the greatest threat to world peace, the communists simultaneously denounced the Truman administration’s foreign policy in the harshest possible terms. Because anticommunist liberalism developed in response to the growing pro-Soviet orientation of Popular Front organizations, the communists deserve the lion’s share of the blame for the rancorous divisions that afflicted postwar liberalism.

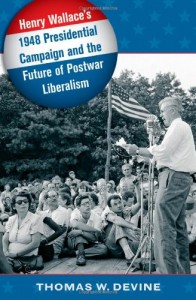

Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace and Ellison D. ‘Cotton Ed’ Smith of the Senate Agriculture Committee meeting in Washington, January, 1939 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Drawing on a wealth of oral interviews, in addition to archival and news media sources, Devine explores the Wallace campaign’s critique of American Cold War policy. In Wallace’s view, American imperialism and domestic fascism represented a far greater threat to world peace than did the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin. The Marshall Plan was nothing but a Wall Street plot to dominate foreign markets and the United States bore sole responsibility for the burgeoning Cold War. Wallace believed the only way to secure world peace was to appease the Soviets by offering a series of concessions to their strategic goals. But as events like the Czech coup and the Soviet blockade of Berlin would demonstrate, Wallace’s belief in the essential goodness of the Soviet leadership was shockingly naïve and out of touch with the vast majority of international public opinion. Because his campaign was launched on the basis of a critique of Truman’s foreign policy, Wallace’s ignorance of foreign affairs and his rose-tinted view of life in the Soviet bloc was his biggest liability. Though Wallace ultimately proved to be an ineffective and unpopular politician, as Oliver Stone’s documentary series makes clear, the radical leftist narrative Wallace championed has endured. This is perhaps in part due to the fact that subsequent U.S. military interventions seemed to prove Wallace’s warnings about the dangers of U.S. Cold War imperialism particularly prescient.

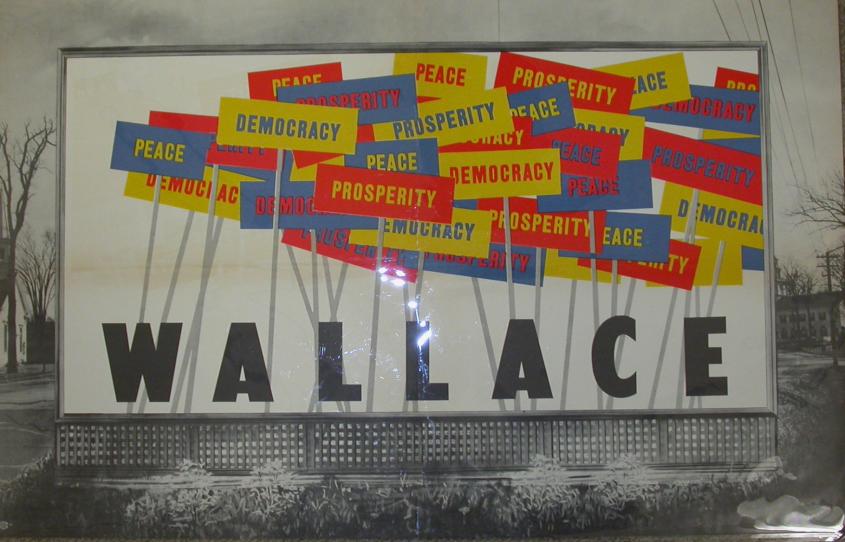

Billboard promoting the 1948 Wallace campaign for President (Image courtesy of the University of Iowa Special Collections)

Devine’s exploration of Wallace’s campaign and the dynamics of the communist-progressive alliance is political history at its finest. Chockablock with colorful quotes, wry asides, and deft understatement, the book is not just a timely and persuasive rejoinder to the popular – though fundamentally misleading – narrative of American postwar liberalism, but is also a genuine pleasure to read.

You may also like:

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines