Traditional maps can portray people and places at certain moments, but they do not capture the dynamism of movement and change over time. And historical texts can describe change over time but lack the visual element that makes it possible to see the multiple dimensions of change at once. However, “The Spatial History Project” is harnessing the power of digital technology to visually animate historical change. A collaboration between historians and computer engineers at Stanford University, this remarkable site hosts maps that actually move, grow and change before your very eyes. You can watch as infectious diseases spread, as railroads expand, as people migrate, and as Nazi concentration camps are built and, as a result, you can gain a better insight on how, and why, it all happened.

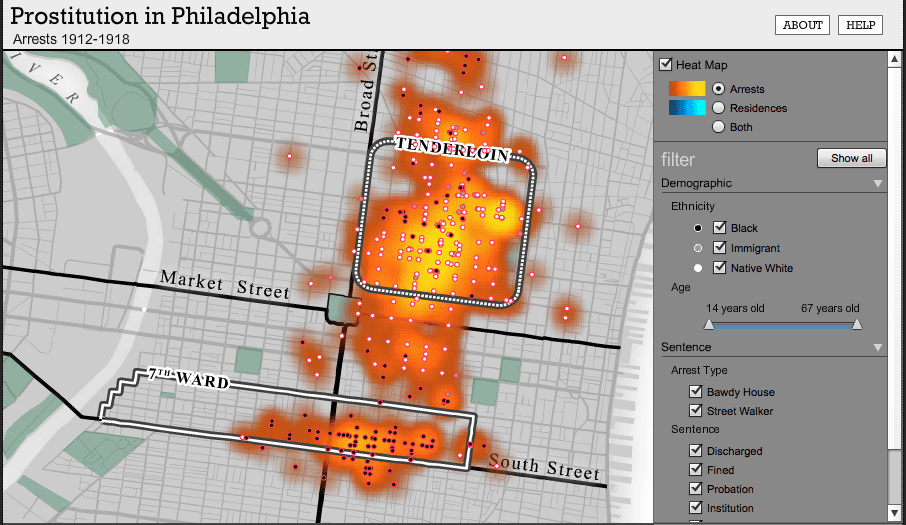

One of the site’s most compelling projects visualizes prostitution arrests in Philadelphia between 1912 and 1918. By splicing a variety of data surrounding these arrests—where the arrest took place, the individual’s racial identity, place of residence, age, among others—we get a deep historical snapshot of who was being arrested for prostitution and where. What emerges is a stark racial divide between the tenderloin district, where “white” arrests largely took place, and the 7th ward, where “black” arrests occurred in greater concentration. Add place of residence data to the map and another fascinating dynamic appears: while “white” offenders largely travel into the tenderloin, most of the “black” and “immigrant” individuals live virtually next door to the brothels. So not only do we see who was arrested for prostitution; we get to see how they got there.

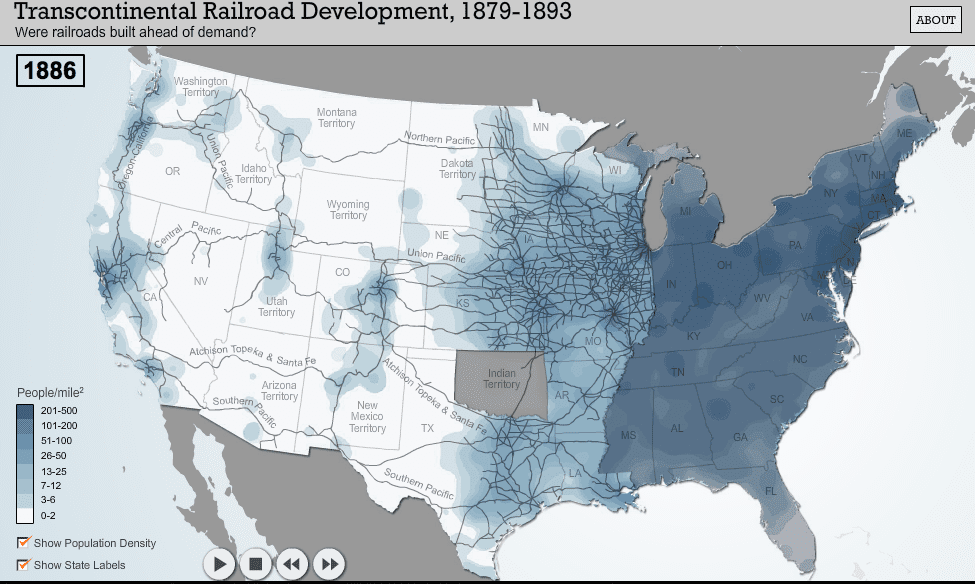

Many of the visualizations specifically challenge traditional narratives of world and US history. “Transcontinental Railroad Development, 1879-1893” allows readers to watch as rail lines creep across the western United States over this 14 year period, connecting major depots such as Chicago and St. Louis with remote frontier lands. But this is not your classic story of westward expansion and economic development. The map integrates population density to demonstrate how sparsely peopled new rail depots were. While rural populations initially grew along new railroad lines, the 1890s depression depleted them back to previous levels, suggesting that railroad companies made critical miscalculations in their rail lines’ organization. By introducing some movement into the mapping of America’s railroads, the story changes.

Many of the visualizations specifically challenge traditional narratives of world and US history. “Transcontinental Railroad Development, 1879-1893” allows readers to watch as rail lines creep across the western United States over this 14 year period, connecting major depots such as Chicago and St. Louis with remote frontier lands. But this is not your classic story of westward expansion and economic development. The map integrates population density to demonstrate how sparsely peopled new rail depots were. While rural populations initially grew along new railroad lines, the 1890s depression depleted them back to previous levels, suggesting that railroad companies made critical miscalculations in their rail lines’ organization. By introducing some movement into the mapping of America’s railroads, the story changes.

“The Spatial History Project” uses digital technology to convey the depth and complexity of history. Its maps depict numerous factors—economics, race, the environment and many others—bisecting and interacting to forge change. And not always the change we assume. This is history as movement, not as a moment.

“The Spatial History Project” uses digital technology to convey the depth and complexity of history. Its maps depict numerous factors—economics, race, the environment and many others—bisecting and interacting to forge change. And not always the change we assume. This is history as movement, not as a moment.

More finds in THE NEW ARCHIVE:

Photo Credits:

Screenshots of the visualizations “Prostitution in Philadelphia: Arrests 1912-1918” and “Transcontinental Railroad Development, 1879-1893,” both taken from “The Spatial History Project”

Workmen celebrate the completion of America’s first Transcontinental Railroad, Promontory Summit, Utah, May 10, 1869 (Image courtesy of National Park Service)