Objects not only inform us about the time and place when they were made, but often have subsequent biographies of use that shed light on later historical developments. Take this wooden drum acquired in Virginia around 1730 and sent to a wealthy collector in England.

Identified as an American Indian artifact, it was one of 71,000 items in the founding collection of the British Museum, the world’s first national public museum. Since its founding in 1753 the British Museum’s collection has grown to more than 8 million objects, yet this drum still holds a special significance. A recent examination of the instrument’s wooden body revealed that it was made in West Africa, even though it had been obtained in North America and was long assumed to be of American Indian origin. Scholars now believe that the drum traveled across the Atlantic in a slave ship and spent some time on a Virginia plantation before winding up in London. It is a remnant, in other words, of the Atlantic slave trade, as well as of the Enlightenment impulse to collect and classify material from around the world.

Identified as an American Indian artifact, it was one of 71,000 items in the founding collection of the British Museum, the world’s first national public museum. Since its founding in 1753 the British Museum’s collection has grown to more than 8 million objects, yet this drum still holds a special significance. A recent examination of the instrument’s wooden body revealed that it was made in West Africa, even though it had been obtained in North America and was long assumed to be of American Indian origin. Scholars now believe that the drum traveled across the Atlantic in a slave ship and spent some time on a Virginia plantation before winding up in London. It is a remnant, in other words, of the Atlantic slave trade, as well as of the Enlightenment impulse to collect and classify material from around the world.

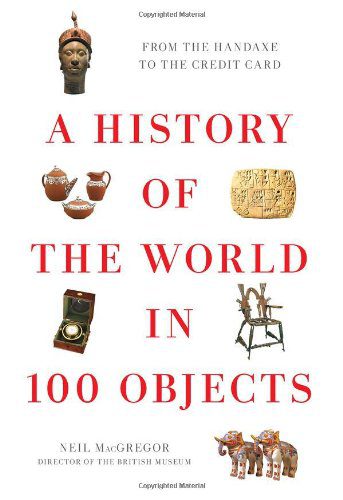

The fascinating past lives of this drum are among the many glimpses into complex historical processes offered by A History of the World in 100 Objects by Neil MacGregor, the Director of the British Museum.

Based on a set of radio programs aired in 2010 by the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) in collaboration with the British Museum, the book is a later print adaptation that closely follows the contents of the radio broadcasts. The twenty parts into which the book is divided, each covering 5 objects, are organized both chronologically and by theme. Collectively, the objects cover a breath-taking expanse of time, beginning with a stone chopping tool from the famous Olduvai Gorge dating back about two million years and ending with a Chinese solar-powered lamp made in 2010. They come from all over the globe: Papua New Guinea, Peru, Pakistan, Paris, and St. Petersburg, among other places.

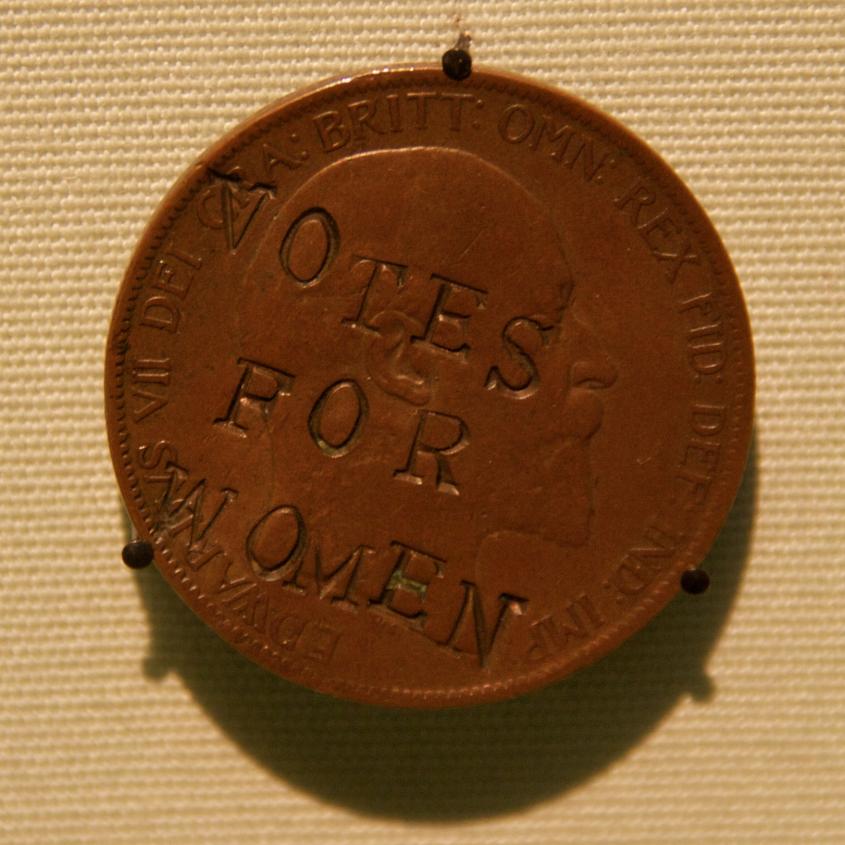

Along with representing numerous societies from around the world, the 100 items also illustrate the wide variety of material objects that humans have created over time. A ceramic roof tile from Korea, a bark shield from Australia, and a North American stone pipe are included in the selection, along with stone sculptures, paintings, and luxury goods that are more typical of museum exhibits. One of the most interesting objects from the perspective of everyday life is a British penny minted in 1903 that someone illegally stamped with the slogan “Votes for Women.” Defacing coinage was among the milder tactics adopted by British suffragettes in their long campaign to obtain voting rights for women, but it was an effective way to spread their message. They finally achieved success in 1918.

Along with representing numerous societies from around the world, the 100 items also illustrate the wide variety of material objects that humans have created over time. A ceramic roof tile from Korea, a bark shield from Australia, and a North American stone pipe are included in the selection, along with stone sculptures, paintings, and luxury goods that are more typical of museum exhibits. One of the most interesting objects from the perspective of everyday life is a British penny minted in 1903 that someone illegally stamped with the slogan “Votes for Women.” Defacing coinage was among the milder tactics adopted by British suffragettes in their long campaign to obtain voting rights for women, but it was an effective way to spread their message. They finally achieved success in 1918.

The diversity of objects contributes to the success of this project, but so too does Neil MacGregor’s engaging style of communication and constant attention to the significance of the artifacts, not only for the societies where they originated but also in terms of the larger world. In the section on the Lewis Chessmen, for example, MacGregor shows how things like chess pieces can teach us about the societies that produced them.

Made out of walrus ivory in the late twelfth century, probably in Norway, the Lewis Chessmen were discovered buried in a sand bank on Lewis Island in 1831. The Norse influence on this part of Scotland is revealed in the “berseker” chess pieces derived from the fierce warriors of Old Norse literature, the equivalent of the modern rook. Another piece in this and other European chess sets, the bishop, replaced the war elephant of the original Indian game, in a reflection on the powerful role played by churchmen in medieval Europe.

Made out of walrus ivory in the late twelfth century, probably in Norway, the Lewis Chessmen were discovered buried in a sand bank on Lewis Island in 1831. The Norse influence on this part of Scotland is revealed in the “berseker” chess pieces derived from the fierce warriors of Old Norse literature, the equivalent of the modern rook. Another piece in this and other European chess sets, the bishop, replaced the war elephant of the original Indian game, in a reflection on the powerful role played by churchmen in medieval Europe.

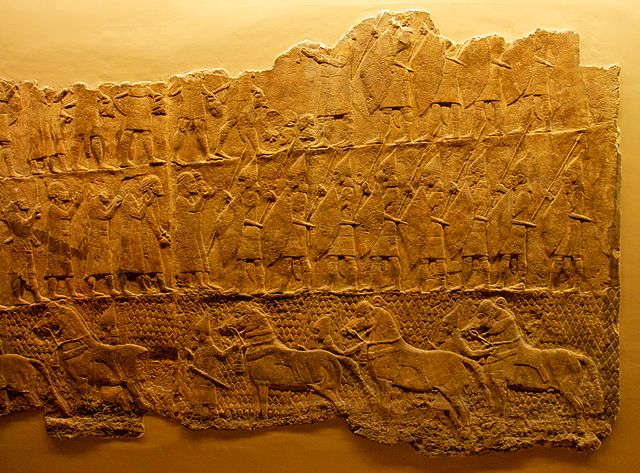

MacGregor is also skilled at highlighting how objects convey human experiences that transcend the barriers of time and place. We learn not only about the techniques of warfare from relief sculpture that depict the conquest of the Biblical town Lachish ca. 700 BCE, but also about the suffering of the local people after they surrendered to the Assyrians. MacGregor compares the Assyrian practice of forcibly resettling conquered populations to Stalin’s mass deportations in the Soviet Union during the 1930s-50s, and to the displacement of many refugees in the recent Balkan conflicts.

All in all, A History of the World in 100 Objects is an impressive achievement: a captivating introduction to the main themes of world history by means of a focus on tangible artifacts. The British Museum and the BBC have done a commendable job of making it accessible to the public, as well, through their companion websites. The original radio programs can still be heard online or downloaded as podcasts, while one or more images of each object can also be viewed along with a map of its original location. There is even a section for teachers containing lesson plans and a game, making this an even more useful resource for the classroom.

All in all, A History of the World in 100 Objects is an impressive achievement: a captivating introduction to the main themes of world history by means of a focus on tangible artifacts. The British Museum and the BBC have done a commendable job of making it accessible to the public, as well, through their companion websites. The original radio programs can still be heard online or downloaded as podcasts, while one or more images of each object can also be viewed along with a map of its original location. There is even a section for teachers containing lesson plans and a game, making this an even more useful resource for the classroom.

Companion websites:

100 Objects at The British Museum

100 Objects at the BBC

You may also like:

Enlightenment: Discovering the World in the Eighteenth Century (2003),

Kim Sloan, editor

“A History of New York in 50 Objects”

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons