By Mary Huber

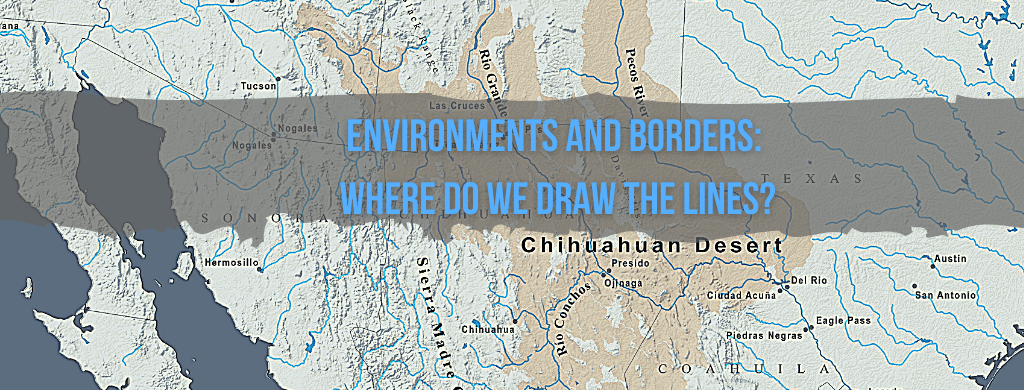

Natural environments seldom follow political borders. While sometimes arbitrary lines on a map separate states, natural environments shape the way people live.

In Texas, people raised in the Gulf Coast wetlands share a similar environment with their counterparts in Louisiana. East Texans who live in the piney woods experience ecological patterns closer to their neighbors in Arkansas. And in West Texas, the desert ties together inhabitants of Texas, New Mexico and Mexico to the south.

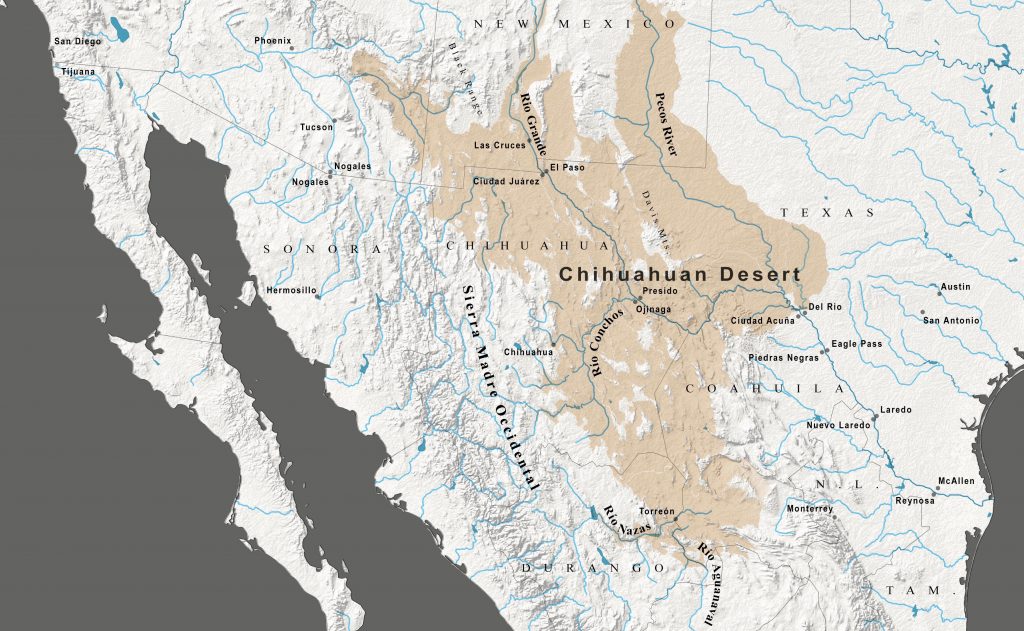

Mexican American and Latino/a Studies Assistant Professor C.J. Alvarez has spent the last three years studying this last group, which he calls “desert dwellers” — people who live in the vast 193,000-square-mile Chihuahuan desert that spans states and national borders. He’s interested in the unique characteristics that define them and that stretch beyond the political borders of nation states.

The Chihuahuan Desert is the biggest desert in North America — about the size of Germany. It encompasses southern New Mexico, West Texas, eastern Chihuahua, and western Coahuila. Despite its large size, Alvarez says many residents of the United States or Mexico would be hard pressed identify it on a map. Historians, too, have often written about deserts from the perspectives of outsiders who saw drylands as either spiritual and artistic places or as harsh wastelands that should be transformed into economically productive spaces through technology and engineering.

“Both of those views — whether you see it as a wasteland or a source of aesthetic inspiration — assume that the desert is an exotic place,” Alvarez says. “I am more interested in the way desert people have understood, seen and experienced the desert in the day-to-day.”

“Most of my research focuses on the 19th and early 20th centuries. In those days almost everyone who lived in the desert had to directly confront desert conditions in their day-to-day lives. Limited water, extreme heat, difficulty caring for animals, and serious agricultural challenges were all part of the package. Some of the most important sources I use to re-create a sense of what life was like back then are oral histories alongside ranch and irrigation records. Very few desert dwellers directly reference the fact that they live in the desert. In fact, they almost never even use the word. Instead, they often talk about the environment in the context of the challenges they face making their lives there.”

Alvarez has been collecting these narratives about desert dwellers and their relationship to the earth as part of the UT grand challenge initiative, Planet Texas 2050, which seeks to mitigate some of the worst effects of climate change over the next decade. Researchers believe that having a better understanding of our state’s varied ecosystems will help us to protect it into the future.

And Texas is the perfect place to do this work.

“Because it’s so big and the political boundaries of the state have only a dim relationship to environmental boundaries, we are actually able to see both sides of the coin of intensified hydrological cycles produced by human-induced climate change,” Alvarez says. “We see extreme wet weather in the storms of the Gulf Coast and extreme drying and droughts in West Texas.”

Alvarez himself grew up in the Chihuahuan desert, in Las Cruces, New Mexico. He says when he was a child, struggled to grasp the nature of floods. “I couldn’t conceive of it,” he says. “I thought it was just for coastal people.”

It turns out that, historically, flooding has been a significant problem in the desert. Unlike the permanent rivers on the Gulf Coast that swell with water when hurricanes roll in, West Texas has what are called arroyos, ephemeral rivers, that flow maybe a few minutes every year during the rare thunderstorms. They cut small canyons and gullies in the landscape, though 99% of the time they are bone dry, Alvarez says.

“But, oh man, when it storms in the right place at the right time, you get flash floods.”

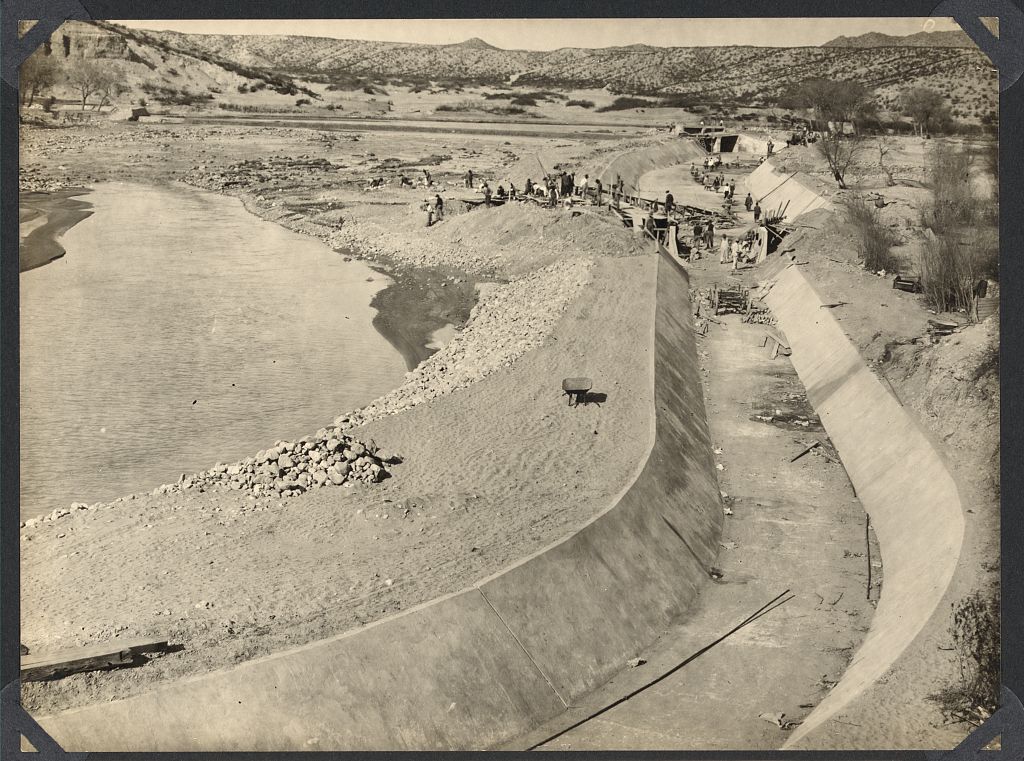

In the middle of the 20th century, construction workers started building unique dams —not to store water for irrigation or interrupt a river system to produce electricity — but to slow down flood water in the rare case of a flash flood. You can see them carved into the landscape around El Paso as well as other desert cities. They have made urban and architectural development in those places possible. Without them, El Paso, for instance, would be destroyed — maybe not next year or the year after, but when the right storm came at the right time, Alvarez says.

“We think about deserts as places whose biggest problem is the dryness, but there is a particular kind of wetness and excess water problem that deserts have that is incredibly dangerous and destructive,” Alvarez says. “This is a specific experience and phenomena for desert people — something outsiders wouldn’t notice.”

Just as desert people have adapted to live with flooding, they have also adapted to live with drought. In the future, they will face additional challenges as these conditions worsen, facing near-permanent damage from overgrazing, as well as drinking water shortages, increased erosion, and depleted irrigation reserves for crops.

“Despite the fact that drylands are often written off as vacant wastelands, they are in fact some of the most fragile environments on earth. Because of this, arid zones will suffer some of the most serious repercussions from climate change, many of which have already begun,” Alvarez says. “Looking back at the history of how people have confronted the extreme conditions of deserts will help us better respond to an uncertain future.”

Mexican American and Latino/a Studies Assistant Professor C.J. Alvarez will be presenting on these topics as part of the Institute for Historical Studies’ “Climate in Context” events, which look at how human interaction with the natural world has changed over time and what valuable information that can provide for addressing our current conditions. Alvarez will speak as part of a panel on April 12 that looks at the history of oil and water in Texas. Jackson School of Geosciences Professor Jay Banner, who is a Planet Texas 2050 researcher, as well, will also present.

For more details and to register, visit IHS Panel: “Oil, Water, and Climate: Environmental Histories of Texas”.

Mary Huber is Communications Coordinator for Bridging Barriers Grand Challenges

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.