By Atar David and Rodrigo Salido Moulinié

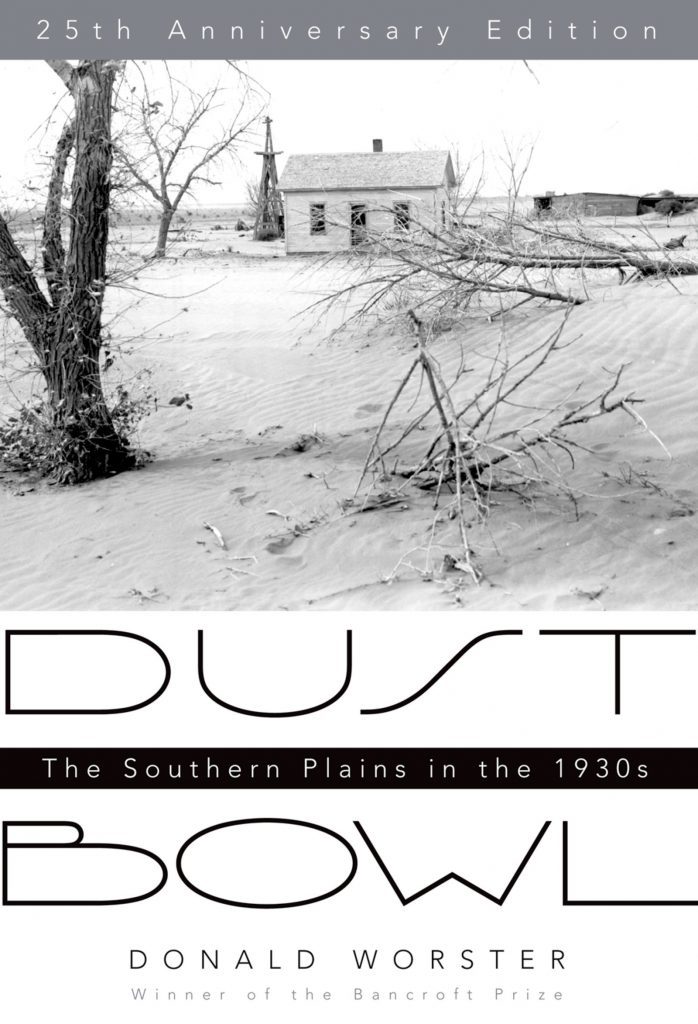

We are excited to present this roundtable review on the 42nd anniversary of Donald Worster’s Dust Bowl, a classic work in environmental history.

***

BOOM, BUST, DUST

Many Americans experienced the 1930s as a nightmare. In the urban centers, the stock market crash of 1929 and the years of economic depression that followed it sent millions of blue-collar workers to stand for hours in breadlines. In the countryside, a series of dust storms, also known as the Dust Bowl, covered vast areas of the Great Plains with dense clouds of sand, destroying fields and farms, forcing families to migrate in large waves. Was it a coincidence? For Donald Worster, the answer is a clear no, and the lessons he draws from that period resonates to today.

In Dust Bowl (1979) Worster argues that both the economic hardship and the environmental catastrophe stemmed from a hyper-capitalist system that, while striving to maximize profits, caused an imbalance in both the markets and nature. Drawing on governmental papers, personal testimonies, and literary sources, Worster demonstrates how farmers and government officials alike promoted a shared vision of agricultural conquest of the plains during the early twentieth century. Within this vision, the land was a source of capital gains, and farmers had both the right and the obligation to extract maximum profits, regardless of the impact on nature. The farmers of Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, and New Mexico fulfilled this capitalist vision. Indeed, according to Worster, the Dust Bowl “came about because the culture was operating in precisely the way it was supposed to” (p.4). Contrary to prior assertions that the Dust Bowl was a natural disaster, Worster reveals that it was people who woke the monster that slept under the once-grassy lands of the plains.

The book is divided into five chapters. Each examines the Dust Bowl from a different perspective. These chapters fall into three sections, each presenting a unique methodological and conceptual contribution. The first two chapters, A Darkling Plain and Prelude to Dust contextualize the dust bowl within the cultural and economic history of the US. Worster demonstrates how the ethos of the agricultural conquest of the plains evolved, was implemented, and eventually collapsed (or, rather, was blown away in the wind). By synthesizing official reports with cultural artifacts, Worster opens new methodological ways of understanding “nature” as a part of a complex cultural and social ecosystem. Later, in chapters three and four, Worster presents the story of the Dust Bowl through the personal testimonies of residents from Oklahoma and Kansas. These chapters reveal not only Worster as a storyteller, but also as a skeptical scholar who questions the narrative of progress many local residents told themselves while dusty particles filled the sky. Lastly, Worster’s fifth chapter connects the Dust Bowl to the historiography of the New Deal. While state officials, ecologists, and agronomists almost immediately recognized the human role in creating the environmental disaster, all three groups failed to implement reforms to restore prosperity to the region. Many of those responsible for utilizing solutions were still bound to the same capitalist and romantic perception of the frontier as a land to be conquered, which Worster argues caused the problem to begin with.

Worster’s analysis raises questions that go beyond the realm of environmental history and encourages readers to think about capitalism, culture, and social structures as well. One such contribution is the idea of “the industrialization of the grassland,” the process by which humans commodified and subordinated nature. This industrialization was first and foremost an intellectual project, in which ideas of progress and prosperity overshadowed notions of conservation and natural equilibrium. Yet, the process was not complete without the introduction of machines and new cultivation techniques that materialized this vision, turning the field into a factory.

For a book published over forty years ago, Dust Bowl seems more relevant today than ever. Readers interested in environmental change will find in it both rich descriptions and methodological inspiration. Other readers will find it a painful reminder to some of our contemporary crises. As I am writing this review, dusty particles from wildfires cover the sky of much of the U.S. west in a clear emblem for the effects of the destructive power of human negligence toward nature. Sadly, Worster’s final words, that “man, therefore, needs another kind of farming by which he can satisfy his needs without making a wasteland” (p.243), still echo today.

Blaming Culture

In his classic book Dust Bowl, Donald Worster traces the causes, consequences, and meanings of a perfect storm that took place in the Great Plains of the 1930s. Drought, global economic collapse, and a deep desire to exploit the land for profit materialized in a dark wall of dust. After years of plowing the land, inescapable dust storms covered the region destroying its harvests and displacing its people. Worster argues that the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression were two sides of the same coin: the American capitalist ethos. The expansionary energy of the Roaring Twenties not only brought machines and resources to the Plains, it brought ideas, values, and specific conceptions of economic order and ecology. In this order, nature served as capital and humans had the duty to exploit it for self-advancement. As Worster puts it: no word that so fully sums up those elements as “capitalism.”

Worster draws from a wide range of sources, from census data and technical reports to personal interviews, photographs, and paintings. These texts, sounds, and images appeared as part of a larger tradition of documenting the U.S. South and West in the thirties and forties. The technical developments that allowed photographic cameras to become portable, practical devices to capture the world emerged at a time of enormous cultural and political shifts. The suffering and urgency of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression opened new avenues for representation and new possibilities of discourse in the arts and sciences. The economic hardships of the South were not new, of course, but the thirties offered novel ways to show and talk about them.

The Dust Bowl happened during the rise of the documentary tradition in the United States that entailed the visual discovery of poor families, fragile houses, and empty landscapes: the Other America. This appeal of the Southern and Western regions of the United States as places to do documentary work linked several fieldwork traditions: travel writing, ethnography in anthropology and sociology, literature, public policy design, and journalism. Photographers of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) such as Walker Evans, Jack Delano, Arthur Rothstein, and Dorothea Lange, writers like James Agee and Erskine Caldwell, and social scientists like Paul Taylor and Howard Odum, all went out to capture this other America, to put it in images and words.

The assemblage of the Other America entailed a series of operations that resembled those of writers, sociologists, and anthropologists going into “the field” or bureaucrats charting new territories. As sites filled with otherness, these regions were then imagined as a geographically close, yet culturally distant place. As regions embedded in backward ways of life and economic hardship, they were also constructed as a temporally distant site: writers and photographers became, like ethnographers, time-travelers.

Worster uses a vast array of sources to show how stories, ideas, and practices make sense—and have concrete, devastating consequences—in the larger webs of meaning of 1930s America. He makes a powerful argument against the inevitability of the Dust Bowl and ecological determinism. Environmental factors alone cannot fully explain the black blizzards: human practices and ideas played the main role by producing an order where profit drives behavior, instead of long-term sustainability.

Although not explicitly at the core of Worster’s book lies a method that ethnographers, photographers, and other fieldworkers employ: empathy. As a way of seeing, as a mode of writing, or as a criterion to navigate sources, wearing the shoes of others shapes Worster’s argument. “The American plainsmen,” he writes, “were as intelligent as the farmers of any part of the world.” Another reason explains why they overrun their environment: “It is the hand of culture that selects out innate human qualities and thereby gives variety to history. It was culture in the main that created the Dust Bowl.”

Having worn those shoes once in his youth, Worster knows his fellow plainspeople will probably dislike his book. It was their ways, and not an ecological anomaly or divine revenge, that caused so much suffering and devastation. Yet Dust Bowl shifts the blame from the actors to a higher concept. “Culture,” it appears, in this case the practices and beliefs associated with a capitalist ethos, explains the black blizzards rather than people. The invisible hand of culture moved them to change the environment and turned it to dust. Farmers who reluctantly accepted the support they desperately needed, but who would go back to overrunning the land as soon as hard times pass, illustrate the underlying problem Worster addresses. In his view, the ethos of American capitalism limits human agency to the point where it dilutes some of their responsibility—to change the landscape and secure its future, the system needs change.

Dust Bowl tells a story of suffering, ecological neglect, misery, and unintended consequences. It also evokes stories it is unable to tell, forgotten tales that got lost amid the dust—a beautiful book. A true classic, the question it poses and the answers it offers retain their relevance: the links between climate change and capitalism, the use of multi-media sources, and what is at stake when using the body and memories to write such an outstanding work. Yet its main contribution today lies beyond tone, scope, and method: it reminds readers of the importance of documenting the world today, the value and difficulty of helping others, and the urgency of posing difficult questions about our ways of life.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.