Judicial records usually provide the empirical grist underpinning historical studies of crime, but journalism is the lifeblood of the field. The efforts of reporters, editors, photographers and illustrators have allowed researchers to resurrect bygone crimes, often in forensic detail. In the more recent Latin American past, for instance, the intrepid sleuthing of journalists—whose “narco libros” populate the Spanish-language shelves of book retailers—has spared academics from treading on paths far more perilous than graduate school could have ever prepared them for. Their revelations pertaining to the inner-workings of criminal syndicates and their state cohorts have deepened our information trove, making it possible for researchers to formulate more comprehensive analyses of the underworld.

It would be unwise, however, to pigeonhole the crime story as a mere chronicle of events, as recourse when police or judicial files are sanitized or inaccessible (as can often be the case in Latin America), or as an aid for imbuing one’s work with the narrative thrust facilitated by the beat reporter’s proclivity for anecdote and imagery. Rather than treating the crime story strictly as a source detailing the particulars of an incident, one would do well to recognize its potential to elucidate a broader range of phenomena, too.

Carlos Monsiváis author of Mexican Postcards (via wikipedia)

Excessively graphic, littered with inaccuracies, and saturated with classist and racist and other biases, Latin American crime papers were once considered little more than pulp trash, and thus beneath serious scholarly engagement. Thankfully, this prejudice seems to be receding. In recent years, a handful of Latin Americanist intellectuals have demonstrated how a rigorous analysis of these sources can yield highly original insights.

Readers could always count on the late Carlos Monsiváis for incisive takes on Mexican life including crime related affairs. In his essay collection on modern culture, Mexican Postcards, Monsiváis asserts that the content and presentation of crime news was profoundly altered after the Revolution (1910-1920). His survey of notas rojas (lit. “red notes/news”)—a popular variety of tabloid showcasing the violence occasioned by robberies, accidents, and crimes of passion—leads him to the conclusion that the press’ crime coverage required a substantial makeover to pique interest and sell papers in the post-revolutionary era. After a decade of storied military feats and charismatic protagonists, standard crime reporting proved forgettable. Striving to provoke visceral reactions and satiate morbid curiosities, nota roja journalists settled on the perfect sensationalist formula: obscenely gory visuals—think severed heads and flayed corpses—plus brief, melodramatic narration devoid of commentary, and crude, often facetious, captions. By the 1960s, entire newspapers adhered to this style, and some even sold in the United States, including ¡Alarma!, the genre’s quintessential publication. Today, many tabloid journalists still bank on the blood of butchered spouses, but they have also mixed drug trafficking stories into their repertoires.

The consolidation of the Mexican drug trade in the 1970s provided an opportunity for certain segments of the press to traffic in a distinct variety of crime story. In the media coverage of the narcotics business, Monsiváis discovered a cult of celebrity built on illusory images of criminality. Rather than minor thievery rings or homicidally jealous lovers, the protagonists of these stories were a different class of criminal who were accorded “the notoriety once reserved for politicians, sports personalities, and film stars.” Their exploits and life stories were related in prose that was reminiscent of early modern picaresque tales. Often, the most unsavory aspects of the criminal experience were omitted, or at least obfuscated by the glamour conferred by power and fortune.

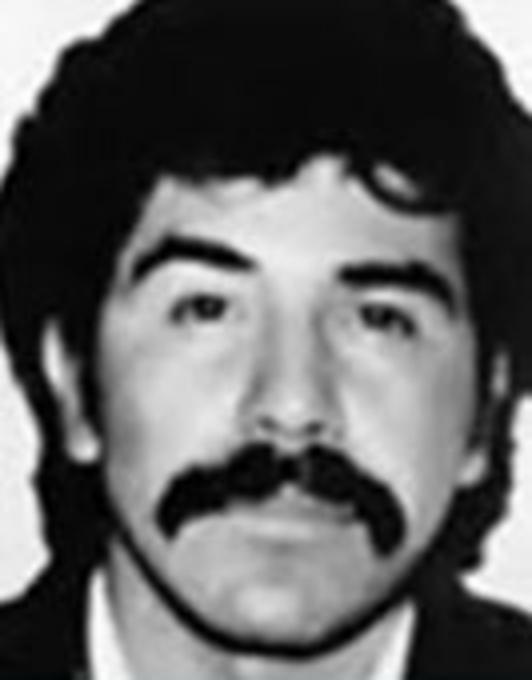

Monsiváis meditates on the case of Rafael Caro Quintero, co-founder of the defunct Guadalajara Cartel. Many tabloids aided in the cultivation of Caro Quintero’s “social bandit” image, despite his being motivated by personal gain. His archetypal rags-to-riches story and supposed beneficence to the Sinaloan backwater from which he emerged were artfully tapped by writers. Seldom did these outlets delve into his organization’s brutal exploitation of poor poppy-farming communities, the effects of their sticky brown product in U.S. cities, or his elbow rubbing with members of Jalisco’s business elite.

Those familiar with the history of the Mexican drug trade will recall that Caro Quintero’s ascendancy was short-lived. On April 4, 1985, he was arrested for his involvement in the prolonged torture and murder of DEA Agent Enrique Camarena. Mexican television broadcast the moment when Caro Quintero and associates were escorted into Interpol’s Mexico City headquarters. Hordes of people tailed the group and shouted “Caro, reveal the corrupt!” “Unmask them all, Caro!” “Names, Caro, names!” Monsiváis likens this scene to that of a revolutionary hero riding into the main plaza of a town, being greeted by a hopeful peasantry awaiting the dissolution of an unjust government. Images of the purported social bandit and anticipated whistleblower beamed across the country.

Rafeal Quintero identification picture (via FBI)

Comparable transformations in crime coverage occurred in Buenos Aires during the interwar period. In While the City Sleeps: A History of Pistoleros, Policemen, and the Crime Beat in Buenos Aires Before Perón, historian Lila Caimari lays the shift in crime reporting at the feet of an array of factors related to “modernity,” namely, technological advances and the importation of U.S. tabloid journalism and Hollywood cinema. This onslaught of variables coalesced to generate what she dubs the new “languages of crime.”

Caimari recounts how in the late 19th century the Buenos Aires press wrote about crime in “natural-scientificist” language that borrowed terminology from medicine, criminal anthropology, and psychiatry. Taking cues from English and French journalists, Argentine reporters played detective by attempting to decipher the cause of a perpetrator’s criminality. But toward the 1930’s, these European influences could no longer compete with the flashier of American tabloids. Argentine editors, cognizant of the public’s insatiable appetite for detective novels and U.S. gangster cinema, quickly adopted a highly stylized, entertainment-driven approach.

The most prominent national media outlets spearheaded what the author calls the “cinematization of crime reporting” by deploying a vibrant assortment of visual and verbal tools. Popular newspapers La Razón, Última Hora, Crítica, and the illustrated Caras y Caretas employed melodramatic language, references to films, theatricalized reconstructions, photographic staging, and comic strips to accompany their narration. Stories were chosen for their similarity to contemporary U.S. criminal practices and featured a new protagonist: the pistolero (lit. “gunman”)—a Capone-esque gangster with the latest technological resources at his disposal. The elements of the criminal performance—weapons, automobiles, attire, and argot—became the main focus for writers, illustrators, and photographers. In stark contrast to the previous century, the question underlying press accounts of the criminal was no longer why he committed his crime, but how. And much like in Mexico, many publications contributed to the legends that shrouded criminals’ careers. Ahora’s stories on the train and bank robber David Segundo Peralta, a.k.a. “Mate Cosido,” were part of a trend in which certain outlets gave organized crime figures the matinee idol treatment.

Following a string of kidnappings—most notably the 1932 abduction and slaying of Abel Ayerza, the son of an affluent family, by Sicilian-Argentine Mafioso Juan Galiffi, a.k.a. “Chicho Grande”—journalists shifted their attention to these protracted dramas. Now, the victims’ families became the main protagonists, and their visible agony instigated a renewed debate over the proper administration of justice. Both the public and media voiced their desire for more stringent laws, heightened police presence on the streets, and the reinstatement of capital punishment.

A few decades later, back in Mexico, an analogous phenomenon transpired as the nota roja assumed the role of bastion of the public sphere. In his latest book, A History of Infamy: Crime, Truth, and Justice in Mexico, Pablo Piccato (UT History Ph.D., 1997), explores civil society’s efforts to mend the ruptured nexus between crime, truth, and justice that emerged during the post-revolutionary era. The inefficiency and corruption of the authorities, coupled with the wiliness of certain criminals, often made it impossible for truth and justice to prevail. Consequently, citizens sought the facts of a case and proper application of the law by engaging in debates in both courtrooms and the press. Jury trials, in which ordinary people attended proceedings to discuss the full gamut of criminal behavior and settle on truths, were a novelty in the country’s legal history. But after their abolition in 1929, the nota roja took over as civil society’s primary marketplace of ideas for crime-related issues.

Unlike Mexico’s leading newspapers, many of which counted on government subsidies to stay afloat, tabloids like ¡Alarma! and Detectives were free to lay bare the collusion between state officials and underworld figures. For readers, these publications came to represent unparalleled sources of important information. Many even made a habit of writing in to opine on a variety of topics, from how police should go about their job, the likely motives of serial killers, and most commonly, to suggest the rectification of heinous crimes via extrajudicial methods. Columnists generally concurred with the latter point, arguing that since capital punishment was no longer an option (it was abolished for civil cases in 1937), jailers should be given carte blanche to dispose of those convicted of the most despicable crimes. Torture, lynching, or a quick and easy bullet to the brain were all deemed fitting punishments. Some favored the so-called ley fuga, or law of flight, a Porfirian-era extrajudicial punishment that empowered police to shoot fleeing prisoners. In practice, however, the police themselves would often set the prisoner free in order to apply the penalty.

At the heart of Piccato’s study is what he describes as “criminal literacy.” Rooted in lessons from both notas rojas and fictional narratives, criminally literacy refers to specific knowledge that was essential to safely navigate the dangers of contemporary Mexico City. It comprised an eclectic mix of information, such as knowing which neighborhoods to avoid, the standard ruses of thieves and con artists, and the potential perils of nightlife. All of this was certainly helpful in staving off victimization, but it undoubtedly reinforced anachronistic ideas about the perceived differences between good, lawful citizens and bad, unlawful ones.

These and a small number of other authors have been wise to treat the crime story with greater seriousness. Consequential narratives about certain types of crimes, malefactors and victims, whether accurate or not, are disseminated through newspapers, magazines, radio and television broadcasts, and even literary works. Unsurprisingly, popular perceptions (as opposed to reality) offer an important indicator of the public’s knowledge. And frankly, sometimes what people believed is more interesting than what actually occurred. Cultural histories of crime writing or criminal archetypes as fostered by the languages of mass communication constitute an alluring new research frontier—a sort of history of popular criminological thought—that have the potential to flourish alongside the more traditional scientific and legal historiographies.

Books Discussed:

Carlos Monsivais. Mexican Postcards. Translated and Introduced by John Kraniauskas (1997)

Lila Caimari. While the City Sleeps: A History of Pistoleros, Policemen, and the Crime Beat in Buenos Aires Before Perón (2016)

Pablo Piccato. A History of Infamy: Crime, Truth, and Justice in Mexico (2017)

Further Reading:

Pablo Ansolabehere and Lila Caimari, editors. La ley de los profanos. Delito, justicia y cultura en Buenos Aires (1870-1940)

Robert Buffington and Pablo Piccato, editors. True Stories of Crime in Modern Mexico

Carlos Monsiváis, Los mil y un velorios: Crónica de la nota roja en México

Sönke Hansen, Between Fiction and Reality: Policiales and the Beginnings of the Yellow Press in Lima, 1940-1960 in Voices of Crime: Constructing and Contesting Social Control in Modern Latin America, Eds. Luz E. Huertas, Bonnie Lucero, and Gregory J. Swedberg