The ethos of the crusading and the chivalric has been used to distinguish the Iberian Catholic colonial expansion in Latin America from the British Protestant colonization of New England. William Prescott, for example, the nineteenth-century historian of the conquest of Mexico, made popular the image of Spanish conquistadors as both benighted medieval throwbacks and chivalric heroes, to explain why Spanish America had developed so differently from British America. Puritan Conquistadors seeks to overcome such distinctions and to demonstrate that many of the justifications for colonization in Puritan colonial Massachusetts were really not that different from those espoused in, say, Catholic colonial Lima. For Puritans and Catholics alike, colonization was an act foreordained by God and prefigured in the trials of the Israelites in Canaan. Puritans and Spanish clerics felt entitled to take over America by force, because they were battling their way into a continent infested by demons. Ultimately, the objective of both religious communities was to transform the “wilderness” into blossoming spiritual “plantations.”

For some European settlers, colonization was an act of forcefully expelling demons from the land by defeating plots Satan devised by manipulating pirates, heretics, indigenous religious revivals, frontier wars, or even imperial policies that weakened colonial settlements. Others saw colonization as a way to physically cast out demons using charms such as crosses or Bibles. Not that the New World was afflicted with more demons than Eurasia. Europeans believed that there were millions of good angels and bad angels, organized as armies all over the world. The problem in the New World was one of entrenchment. Since the spread of the gospel with the apostles, the devil had had time to build “fortifications” there and set deep roots both in the landscape and among the people.

Spanish friars found among the Aztecs Satan’s ultimate mockery of God, namely, a society whose history and institutions seemed to be an inverted mirror image of those of the Israelites. Lucifer’s mockery of the Eucharist and the miracle of transubstantiation, for example, seemed to take place every week on the steps of the temple of Huitzilopochtili, where the bodies and hearts of sacrificed warriors were served to the masses to enjoy as morsels. Curiously, once the friars embraced the natives as the ideal pliable clay with which to build the Church of the millennium, and once the friars began to vie with the settlers for control of the bodies (not the souls) of the natives, the friars became more prone to see the wiles of Satan in the New World manifested in the actions of the very sons and daughters of the conquistadors, born and raised in the New World and known as Creoles.

Creoles, in turn, came to find the devil among Spanish newcomers. Creoles, for example, passionately embraced the cult of Our Lady of Guadalupe because they saw a prophecy of the conquest of the Aztecs by Hernán Cortés in the battles waged between the Dragon and the archangel Michael in Revelation 12. But Creoles also thought that the book of Revelation anticipated the sufferings of the conquistadors’ heirs in America at the hands of satanic peninsular upstarts. Creoles liked to imagine the uppity newcomers as Satan’s allies. Finally Spaniards also identified the battles against Satan in the New World as part of a much larger geopolitical struggle pitting God against Lucifer, in which both Muslim pirates in the Mediterranean and English privateers in the Caribbean played their parts.

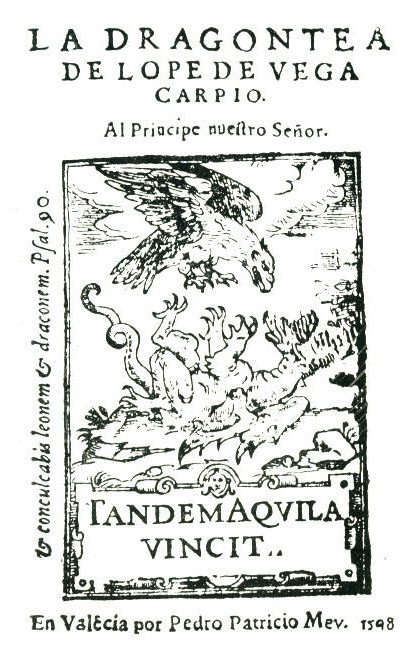

English Protestants first found the devil in America among the Spaniards, not the Amerindians. In Elizabethan England, the figure of the privateer, a pillaging soldier of fortune who, like the Spanish conquistador, sought treasure and entry into the ranks of the grandees, became the equivalent of the Spanish conquistador battling Satan. Ruthless, plundering, lowly hidalgos like Francis Drake appeared in numerous satanic epics as heroes bleeding the Spanish Antichrist white.

But by the time of the arrival of the Puritans in the New World, perceptions of who the main ally of the Devil was began to shift. This shift coincided with the Pequot War (1637), which started as a petty squabble in the Connecticut River valley among the Dutch, English, Mohegan, Narragansett, and Pequot over access to pelts, wampum, and regional hegemony. Demonology played a significant role in turning that squabble into a Manichean battle pitting the godly Puritans against Satan’s minions, the Pequot. The view of the Pequot as demonic moved the Puritans to collect scalps and hands of enemy warriors as trophies and to regard burning Indian children and women alive as heroic.

Puritans viewed the devil as an external enemy who threatened the polity. The Salem witchcraft outbreak can only be explained in the context of the siege mentality that began to develop in Essex County in the wake of King Philip’s War. For two decades, Puritans experienced all sorts of setbacks, including epidemics, loss of political autonomy vis-à-vis the English Crown, Quaker encroachment, failed campaigns against the French, and constant frontier warfare with the natives. Puritan magistrates saw Satan as an enemy not only working within the soul but also harassing the community from without. Thus the clergy during the Salem crisis found themselves willing to punish as demonic anybody deemed to be an outsider: spinsters with connections to Quakers and to the Amerindian frontier. Salem’s witches were deemed by Puritans to be allies of the Amerindians or the French and thus Satan’s minions in the larger struggle for control of the northeastern frontier.

By showing the common roots of Spanish and British American discourses of colonization, Puritan Conquistadors puts the much vaunted exceptionalism of North American Anglo-Protestant culture in an international context.

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares, Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-1700

Great Books on Atlantic Empires

Images:

Benjamin Thompson, Sad and Deplorable Newes from New England (London, 1676).

Lope de Vega, La Dragontea (Valencia, 1598).