By Nikki Lopez

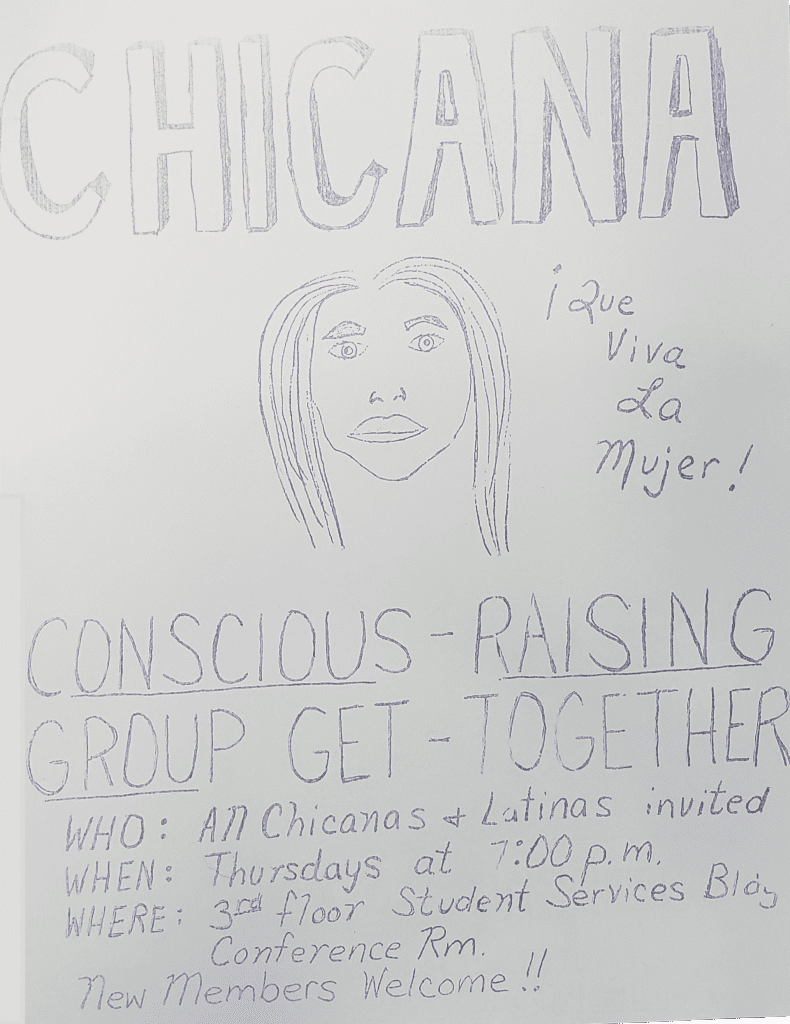

“I think I drew it in my apartment, I drew a lot of posters for organizations from Austin to San Marcos,” Cynthia Orozco answered when I asked about the origins of the poster. Orozco further explained to me that feminist consciousness groups like this one were popular in the late 1970s. “It was just a place where we talked about sexism on campus with around ten Chicanas. It was a group where we felt safe.” Cynthia Orozco’s life was filled with many such posters, little moments of struggle that combined to make a difference in her life and the lives of the Chicanas who followed her at UT.

I interviewed Dr. Cynthia Orozco about her upbringing and her time at UT. Orozco grew up in Cuero, Texas, in a low-income, working-class family. Her mother, Aurora, passionately advocated for educational access for minorities and had been involved with the Mexican American civil rights movement since the 1950s. “My mother attended a segregated school. ‘Mexicans are stupid people’ was a phrase she heard frequently.” Aurora’s primary motivation behind her advocacy work was racial discrimination in Cuero schools that directly affected her own children. Later all seven of her children, including Aurora, would go on to attend The University of Texas at Austin. Orozco would continue to pursue her family tradition of activism. During her high school graduation speech, Orozco called for the school system to stop ignoring women and minorities and forcing boys to cut their hair. In retaliation, the school fired her from her student council position. “We knew that it was possibly illegal what they did, but at that time we really couldn’t do anything.”

Orozco found new opportunities and challenges at UT. Following a two-year stint at Southwest Texas University (now Texas State), Orozco enrolled at UT in 1978. During her time at UT, Orozco was able to experience first-hand how sexism and racism intertwined and left her out of place in the Chicano organizations. The underlying sexism in the movement was perpetuated by the idea of La Familia, which reinforced traditional, paternalistic patterns, and marginalized women and women’s issues in the Chicano movement. “I have learned that the Chicano movement is just that, a ChicanO movement which uses women as workers, sucks our life blood and does not return our due benefits,” Orozco wrote in an editorial for La Gente in 1981. For many in the Chicano movement, the needs of Chicanas were not important and sexism was normalized subconsciously. Discussions at group meetings focused on addressing racism and not sexism.

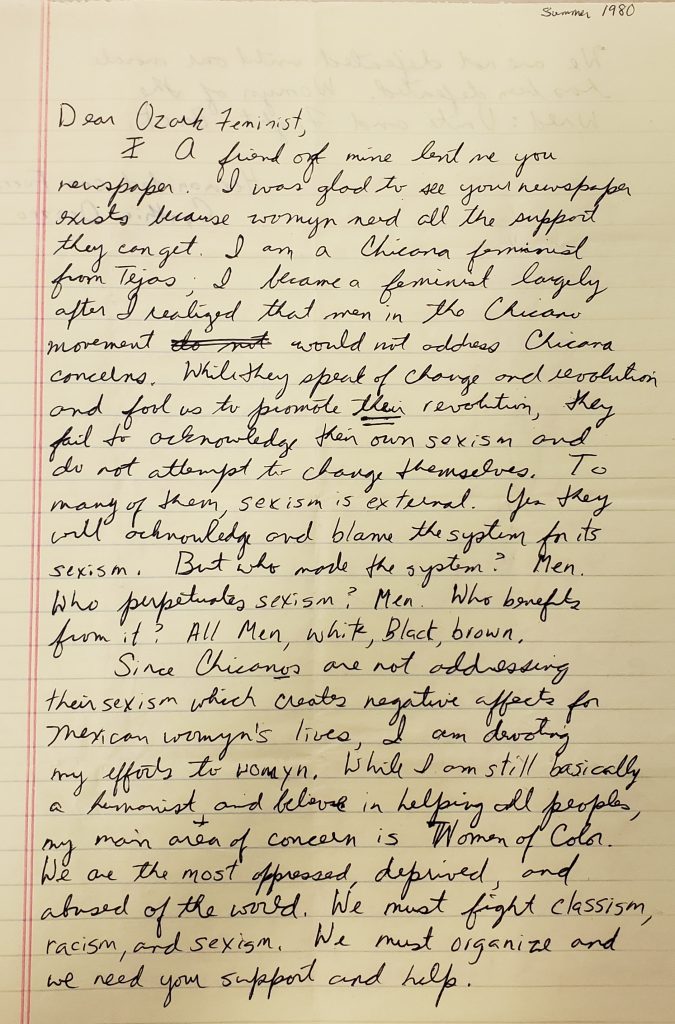

Throughout her life Cynthia Orozco spoke out against institutions that tried to suppress her and held firm to her beliefs. Orozco was constantly silenced and seen as a burden due to her vocalizing the need for Chicana representation during student-led meetings and conferences. Orozco recalled in her editorial for La Gente that during an organizing meeting for an event in 1979, she “was told by an activist that one woman was already included in the schedule” and there was no need for any more. The rationalization behind excluding women-centered sessions was that issues pertaining to police brutality and farmworkers’ rights were more important. Students in the group (including women) voted against the crucial inclusion of Chicana voices. Angry with Chicano groups, Orozco wrote an article called “On Chicana Unity” for The Daily Texan. She criticized her “brothers” for their lack of flexibility when considering the role Chicanas in the movement and prefered that their “sisters” remain home as mothers. Once while she was studying, Orozco received multiple calls from the UT Chicano Community leader screaming at her that she was causing the movement to be divisive and continuing to invalidate her Chicana identity. In a letter to a fellow feminist, Orozco wrote that “while I am still basically a feminist and believe in helping all people, my main area of concern is Women of Color.” Following in the tradition of radical feminists who came before her, Orozco established a feminist collective called the Chicana Consciousness Group. The collective met every Monday and became a home for many students on campus. Members were able to breathe and share their thoughts that they felt scared to share in other organizations.

Despite the struggles she faced, Orozco felt that UT was “one of the most academically, enriching universities out there.” UT helped her think outside the box and pushed her to take on an active role in writing and research. Beyond the Chicana Consciousness Group, Orozco used her position in student leadership roles to help other students learn from scholars. Orozco was Chair of the Chicano Culture Committee to invite women to share their research. “There was always something going on campus! I attended workshops and enjoyed the ones I planned as well.”

Despite our separation in time and space, I can see myself in Cynthia’s poster. During our interview Orozco mentioned that she began to have an identity crisis at UT. The feeling of not being Mexican or American enough is a struggle that I shared. Unlike Orozco I’ve had the privilege to take classes that are Chicana-centered. These classes were designed for people like Orozco and me.. They taught me that my feelings were valid and that my identity was seen. Orozco had to do this on her own with the resources she had. She advocated and created a space even though the work was exhausting. Thanks to her advocacy students like me have been able to navigate UT better.

Our America: A Hispanic History of the United States

Women Shaping Texas in the Twentieth Century