By Camila Ordorica

Note: This bilingual article appears first in Spanish and then in English.

Por segunda vez en los 73 años desde su creación, este año UT Austin será la sede de la XVI Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México, la cual se celebrará del 30 de octubre al 2 de noviembre. Bajo la coordinación de un comité conjunto presidido por la Dra. Susie Porter, de la Universidad de Utah, el Dr. Pablo Yankelevich, de El Colegio de México, y el Dr. Matthew Butler, como organizador local de UT-Austin , la conferencia convoca a un diálogo sobre la relación binacional entre México y Estados Unidos (y más específicamente Texas), así como sobre archivos. ¿Cómo ha cambiado la escritura de la historia sobre México y la frontera desde la última vez que la Reunión se celebró aquí, en 1958? Este artículo presenta una breve historia de las Reuniones Internacionales de Historiadores de México desde 1949 y ofrece algunas notas sobre cómo ha cambiado desde entonces la escritura de la historia sobre México y sus fronteras.

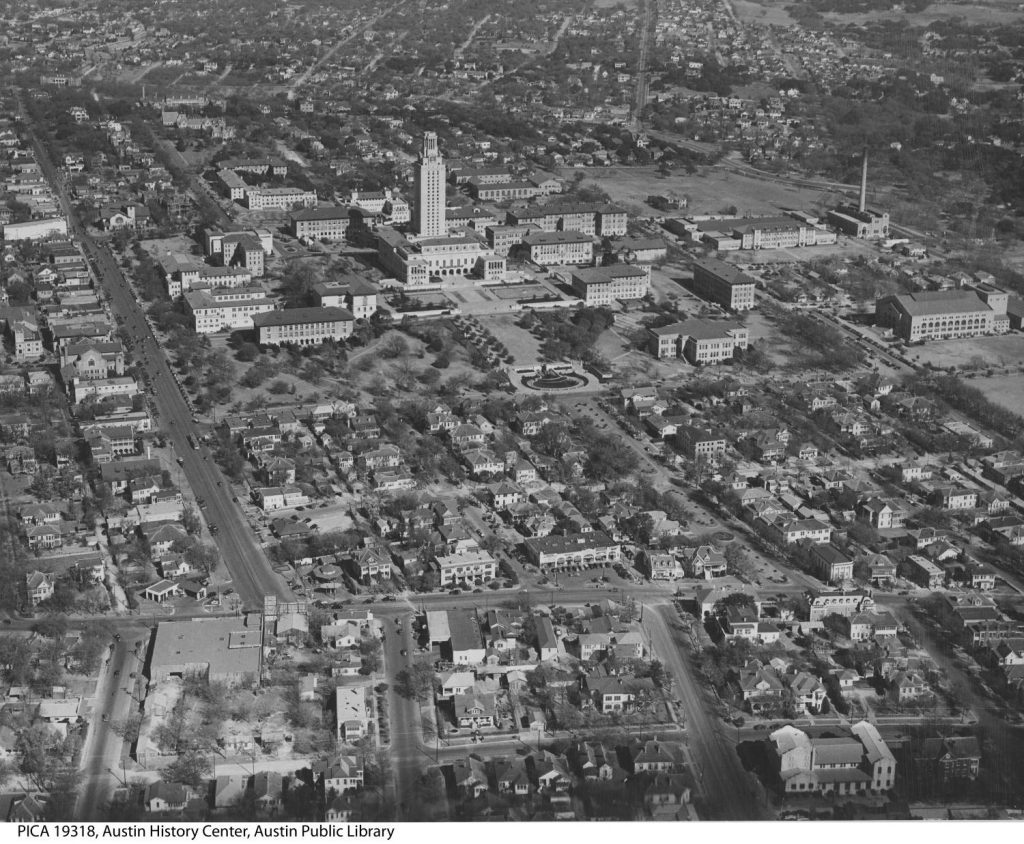

For the second time in the 73 years since its inception, UT Austin will host the XVI Meeting of International Historians of Mexico, which will be held from October 30th to November 2nd. Under the coordination of a joint committee chaired by Dr. Susie Porter of the University of Utah, Dr. Pablo Yankelevich of El Colegio de México, and Dr. Matthew Butler as UT-Austin’s local organizer, the conference is planned to be a dialogue concerning the binational relationship between Mexico and the United States—and more specifically Texas—and about archives. How has the writing of Mexican and borderland history changed in the last time the meeting took place here, in 1958? This article presents a brief history of International Historians Meetings beginning in 1949 and gives some notes on how historical writing about Mexico and its borders has changed since then.

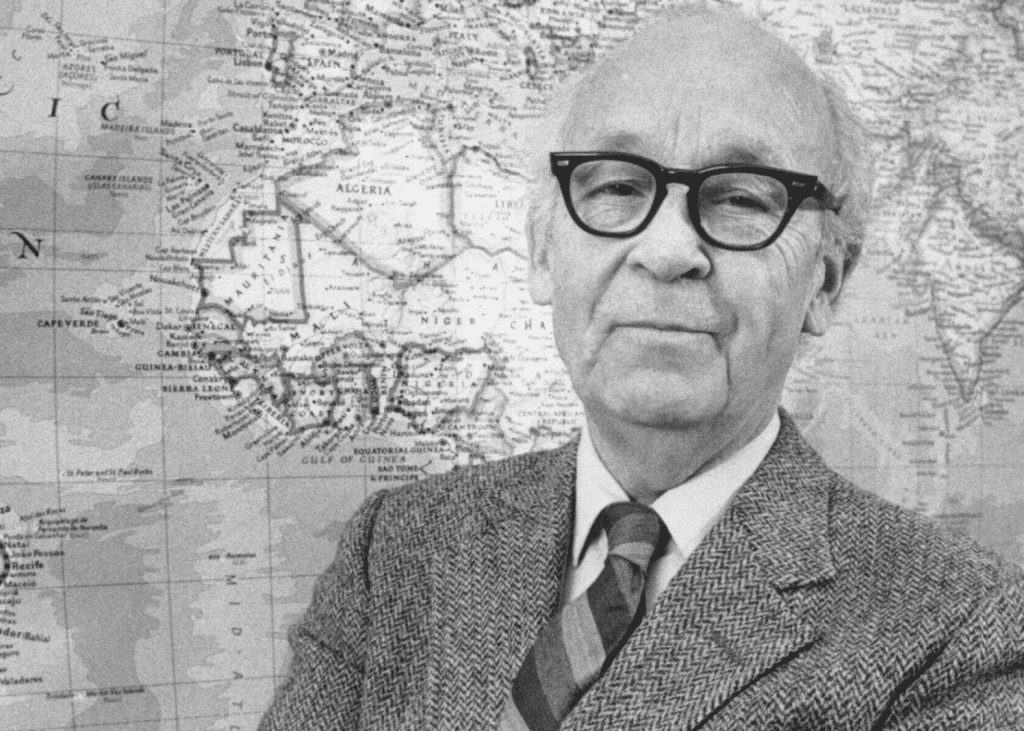

Corría el año de 1949 cuando el historiador mexicano Silvio Zavala, como parte de los esfuerzos de contribuir a la profesionalización de la disciplina histórica en México organizó el Primer Congreso de los Historiadores de México y los Estados Unidos que se llevó a cabo en la ciudad de Monterrey. El objetivo de éste fue generar y enriquecer los lazos internacionales de diálogo e intercambio entre historiadores de ambos países con la finalidad de establecer contacto entre los estudiosos, organizar investigaciones, fundar nuevas sociedades, así como sistematizar nuevas revistas e innovar en la enseñanza de la antropología y la historia.[1] Nueve años después, en 1958, la reunión se replicó en la Universidad de Texas en Austin, presidiendo este segundo evento Lewis Hanke, historiador del mundo lascasiano. Con un propósito similar, la conferencia estuvo enfocada en el diálogo sobre las fronteras, principalmente la frontera México-Estados Unidos, aunque también se habló de fronteras medievales en España y las fronteras de América Latina, como fue el caso de las fronteras de Brasil y Argentina. A propósito de este bilateralismo, se hicieron presentes intelectuales emblemáticos como Antonio Castro Leal, J. Frank Dobie, y François Chevalier, y asistieron los gobernadores de Texas y de Nuevo León a el banquete final. Además, una sesión fue patrocinada por la Comisión de Buena Vecindad del Estado de Texas. De meros escribanos estuvieron un tal Luis González y González y Edith Parker, única mujer que se menciona en todo el programa.[2]

De acuerdo con las memorias que escribió el propio Hanke, estas dos reuniones iniciales fueron de las primeras iniciativas binacionales de intercambio académico exitosas, ya que múltiples esfuerzos se habían realizado en el continente sin demasiado consecución.[3] Sin embargo, a pesar del éxito de éstas, pasaron once años hasta que en 1969 se realizó la tercera reunión en la ciudad de Oaxtepec en Morelos, cuyo presidente fue Daniel Cosío Villegas, economista y gran historiador del liberalismo mexicano. En esta edición, se presentaron nuevas directrices de la historiografía mexicana así como los avances y cambios en la disciplina desde la primera reunión, veinte años atrás. Como parte de las conclusiones de esta tercera reunión, se estableció un Comité Organizador que se encargaría de sistematizar estas reuniones. Desde entonces, las Reuniones Internacionales de Historiadores de México se llevan a cabo cada cuatro años y se alternan entre una ciudad mexicana y una ciudad estadounidense, con la excepción de 2006 cuando la ciudad huésped fue Vancouver. Además de los presidentes de congreso ya mencionados, las reuniones concurrentes fueron encabezadas por las siguientes personas: Nettie Lee Benson (Santa Mónica, 1973), Edmundo O’Gorman (Pátzcuaro, 1977), Woodrow Borah (Chicago, 1981), Miguel León-Portilla (Oaxaca, 1985), David J. Weber (San Diego, 1990), Luis González y González (México, 1994), Charles A. Hale (Forth Worth, 1999), Josefina Zoraida Vázquez (Monterrey, 2003), Christian Archer (Vancouver, 2006), Enrique Florescano Mayet y Friedrich Katz (Santiago de Querétaro, 2010), John Coatsworth (Chicago, 2014) y Óscar Mazín (Guadalajara, 2018).[4]

En cada una de sus instancias, la Reunión ha tenido una temática específica alrededor de la cual se organizan las mesas de discusión, las cuales igualmente responden a las problemáticas de la historiografía mexicana y sobre México. Además, todas y cada una de ellas han sido organizadas en conjunción de múltiples instituciones de ambos países así como de Canadá desde el año de 1995. Así, en términos generales, estas reuniones han contribuido ampliamente al desarrollo de una historia mexicana con carácter hemisférico y global tanto en su estudio como en su producción y aplicación.

En el año que corre se llevará a cabo la XVI Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México, del 30 de octubre al 2 de noviembre, en la Universidad de Texas en Austin, bajo la coordinación del comité organizador conjunto que dirigen la Dra. Susie Porter de la Universidad de Utah, y el Dr. Pablo Yankelevich de El Colegio de México. El Dr. Matthew Butler (UT-Austin), es coordinador local. Después de Monterrey (1949 y 2003), ésta será la segunda instancia de la Reunión que será en una ciudad y en una universidad donde ya se había auspiciado con anterioridad. En el marco de la próxima conmemoración del bicentenario de la Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (1824) que incluía a Texas, este año el tema de la XVI Reunión es “Federalismos en la historia de México y México-Texas”. La XVI Reunión pretende entablar un diálogo sobre la relación binacional entre México y Estados Unidos, pero más específicamente con Texas, bajo un paradigma político y hemisférico distinto al que existía hace dos siglos y que, sin lugar a dudas, ha tenido muchos cambios desde que la II Reunión en 1958. Aunado a esto, la XVI Reunión se une a las conmemoraciones universitarias del centenario de los archivos históricos de América Latina Nettie Lee Benson con el objetivo explícito de reflexionar críticamente sobre lo que significan los archivos y la documentación histórica en términos de libertad de acceso a un patrimonio en común, apostando por la colaboración archivística internacional en favor de la escritura, el acceso, y la salvaguarda de la historia.[5]

Ante esto, ¿cómo ha cambiado la escritura de la historia de México y de la frontera en los últimos sesenta y cuatro años desde la II Reunión? Resulta interesante pensar esta pregunta frente a las actas publicadas sobre la II Reunión en el libro The New World Looks at its History: Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Historians of the United States and Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1963), sobre las cuales resaltan las conclusiones y los mayores descubrimientos. Entre ellos encontramos un punto principal, a partir del cual se desplegaron otras temáticas de análisis: la idea de la frontera como producción sociocultural con origen occidental.[6] Más específicamente aún, las actas resaltan el descubrimiento de que “el Río Grande era un límite moderno completamente artificial entre las culturas indígenas del norte de México y los Estados Unidos sin ningún significado académico.”[7] Vista desde los ojos del 2022, esta declaración––el programa de 1958 habla del “Gran Concepto de la Frontera” (The Great Frontier Concept)––parece hasta inocente, dado que el carácter sociocultural y tecnológico de las fronteras es algo que está ampliamente aceptado como verídico dentro de la disciplina histórica en particular y de las humanidades y ciencias sociales en general. Sin embargo, vale la pena resaltar que esta idea que hoy en día está tan normalizada tiene su propia historicidad, dentro de la cual la II Reunión tuvo un papel para su desarrollo y su institucionalización como un área de estudios en sí mismo, los llamados Estudios de Fronteras o Borderland Studies en las décadas de los setenta y ochenta. Para que hoy en día la frontera México-Estados Unidos y consecuentemente las demás fronteras en el mundo se vean y entiendan como parte de procesos de contingencia histórica, fue necesario y primordial que, en primera instancia, se llegara a esta realización histórica. Por lo tanto, no es de sorprender que este hallazgo se diera en el contexto de un conversatorio internacional, desde el cual la superposición de diversas formas de ver y hacer historia tuvieron la cabida necesaria para resaltar una problemática en común: el territorio y su gobernanza.

Hoy en día, la frontera que divide a México y Estados Unidos mide 3,185kms de largo. Esta es una de las fronteras más largas y letales del mundo y atraviesa los estados mexicanos de Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, y Tamaulipas y los estados norteamericanos de California, Arizona, Nuevo México, y Texas. En ella confluyen múltiples y diversas comunidades que viven una vida compartida entre ambos países o que, en su fallo, quedaron de tal o cual lado de la misma en razón de la distribución geopolítica organizada después de la Invasión Norte Americana en 1848. En el mundo híper-globalizado de hoy, esta frontera se caracteriza por el alto grado de vigilancia, versatilidad y violencia donde, como menciona Sayak Valencia, se “transforman e integran los mercados locales, el trabajo, la territorialidad, las normas jurídicas, los idiomas y la fuerza de trabajo sexualizada.”[8] Además, en ella confluyen los crecientes y constantes procesos de migración desde América Latina, donde cientos de personas mueren cada año en el intento de “cruzar al otro lado.” Así, dado que la frontera es una línea imaginaria pero a la vez híper-real, en ésta se han instaurado dinámicas dobles que hacen del espacio un lugar donde “todo se vale,”[9] volviendo un lugar de perpetua violencia que, ante todo, busca obstruir los tráficos económicos y migratorios. El muro que separa ambos países y que es constantemente engrandecido representa más que cualquier cosa la artificialidad de este límite moderno de cuya realidad se asombraron los académicos durante la II Reunión de 1958. Hoy, hablar sobre federalismos en la relación de México y Estados Unidos sin hablar también de la frontera es imposible, así que valdrá la pena escuchar las conversaciones que surgan al respecto en la XVI Reunión a finales de octubre de este año.

XVI Meeting of International Historians of Mexico in History

It was in 1949 that Mexican historian Silvio Zavala, as part of his efforts to professionalize the historical discipline in Mexico, organized the First Congress of Historians of Mexico and the United States, which was held in the city of Monterrey. Its objective was to deepen the international ties between historians of both countries, increase dialogue and exchange, establish contact between scholars, organize research, and found new societies, as well as to systematize new journals and innovate in the teaching of anthropology and history.[1] Nine years later, in 1958, a second meeting was held at the University of Texas at Austin, with Lewis Hanke, a historian of the world of Bartolomé de Las Casas, presiding over the event. While having a similar purpose, the conference focused on a dialogue about borders, mainly the Mexico-United States border, although there was also discussion of medieval borders in Spain and the borders of Latin America, as was the case with the borders of Brazil and Argentina. This bilateralism was symbolized in the attendance of intellectuals like Antonio Castro Leal, J. Frank Dobie, and François Chevalier, and the governors of Texas and Nuevo León attended the final banquet. In addition, a session was sponsored by the Good Neighbor Commission of the State of Texas. Present as mere recorders were one Luis González y González and Edith Parker, the only woman mentioned in the entire program.[2]

According to Hanke’s own memoirs, these two initial meetings were among the first successful binational academic exchange initiatives, though multiple crossborder efforts had been made before without much success.[3] However, despite their success, eleven years passed before the third meeting was held in 1969 in the city of Oaxtepec in Morelos, where the president was Daniel Cosío Villegas, the economist and great historian of Mexican liberalism. In this iteration of the conference, new directions for Mexican historiography were set out, and the advances and changes in the discipline since the first meeting twenty years earlier were discussed. As one outcome of this third meeting, an Organizing Committee was established to systematize future meetings. Since then, the Meetings of International Historians of Mexico have been held every four years and alternate between a Mexican city and a U.S. city, with the exception of 2006 when the host city was Vancouver. In addition to the aforementioned conference presidents, the respective meetings were headed by the following persons: Nettie Lee Benson (Santa Monica, 1973), Edmundo O’Gorman (Pátzcuaro, 1977), Woodrow Borah (Chicago, 1981), Miguel León-Portilla (Oaxaca, 1985), David J. Weber (San Diego, 1990), Luis González y González (Mexico City, 1994), Charles A. Hale (Fort Worth, 1999), Josefina Zoraida Vázquez (Monterrey, 2003), Christian Archer (Vancouver, 2006), Enrique Florescano Mayet and Friedrich Katz (Santiago de Querétaro, 2010), John Coatsworth (Chicago, 2014) and Óscar Mazín (Guadalajara, 2018).[4]

In each of its iterations, the Meeting has had a specific theme around which the panels were organized, a theme that also responds to the problems of Mexican historiography as well as issues affecting Mexico. In addition, every conference has been organized by multiple institutions from both countries as well as from Canada since 1995. In general terms, these meetings have contributed broadly to the development of a Mexican history that is hemispheric and global in character, both in its study and production and in its application.

This year, the XVI Meeting of International Historians of Mexico will be held from October 30th to November 2nd at the University of Texas at Austin, under the coordination of the joint organizing committee led by Dr. Susie Porter of the University of Utah and Dr. Pablo Yankelevich of El Colegio de México. Dr. Matthew Butler (UT-Austin) is local organizer. After Monterrey (1949 and 2003), this is only the second time that the Meeting is to be held in a city and university where it has been hosted before. Within the framework of the upcoming commemoration of the bicentennial of the Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States (1824), which included Texas, the theme of the XVI Meeting this year is “Federalisms in the history of Mexico and Mexico-Texas.” The XVI Meeting aims to engage in a dialogue concerning the binational relationship between Mexico and the United States, and more specifically Texas, under a political and hemispheric paradigm very different to that of two centuries ago and which, undoubtedly, has also undergone many changes since the II Meeting in 1958. In addition, the XVI Meeting complements the University’s commemoration of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection and has as one objective a critical reflection on the meaning of archives and historical documentation in terms of freedom of access to a common patrimony, especially concerning the promotion of international archival collaborations and the shared writing of, access to, and safeguarding of history.[5]

How has the writing of Mexican and border history changed in the last sixty-four years since the Second Meeting? It is interesting to think about this question in light of the proceedings published on the II Meeting in the book The New World Looks at its History: Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Historians of the United States and Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1963). The book’s conclusions and major discoveries stand out. Among them we find a main point, from which other lines of analysis emerged: the idea of the frontier as a sociocultural construction of Western origin.[6] More specifically still, the proceedings find that “the Rio Grande was a completely artificial modern boundary between the indigenous cultures of northern Mexico and the United States with no scholarly significance.”[7] Viewed through the eyes of 2022, this statement–the 1958 program speaks of “The Great Frontier Concept”–seems almost naive, given that the sociocultural and technological character of borders is widely accepted within the historical discipline in particular and the humanities and social sciences in general. However, it is worth noting that an idea that is so standard today has its own historicity, and that the Second Meeting played a role in developing and institutionalizing this idea as an area of enquiry in its own right, the so-called Borderlands Studies in the 1970s and 1980s. In order for the U. S.-Mexico border and consequently other borders around the world to be seen and understood today as part of contingent historical processes, it was necessary and essential that this historical realization first be achieved. Therefore, it is not surprising that this finding emerged in part from an international dialogue, in which diverse ways of seeing and making history were given the necessary space to converge and so highlight a common problem: territory and its governance.

Today, the border that divides Mexico and the United States is 3,185 kilometers long. It is one of the longest and most lethal borders in the world and passes through the Mexican states of Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas, and the U. S. states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Along it converge multiple diverse communities that live a shared life between two countries or that, by default, have remained on this side or that of the border due to the geopolitical redistribution that occurred after the U. S. Invasion of 1848. In today’s hyper-globalized world, this border is characterized by a high degree of surveillance, versatility, and violence. As Sayak Valencia has noted, it is where “local markets, labor, territoriality, legal norms, languages and sexualized labor forces are transformed and integrated.”[8] Moreover, it is where the growing and constant processes of migration from Latin America converge, where hundreds of people die each year in an attempt to “cross to the other side.” Given that the border is an imaginary but at the same time hyper-real line, dual dynamics play out there, turning the space into a place where “anything goes,”[9] a place of perpetual violence that, above all, seeks to obstruct economic and migratory traffic. The wall that separates the two countries is constantly enlarged. More than anything else, this represents the artificiality of this modern boundary whose reality astonished the academics at the II Meeting in 1958. Today, to talk about federalism in the relationship between Mexico and the United States without also talking about the border is impossible, so it will be worthwhile to listen to the conversations that emerge in this regard at the XVI Meeting at the end of October of this year.

[1] Manuel Ceballos Ramírez. Historiadores. Cincuenta años de reuniones internacionales, 1949-1999. México, Monterrey, 1999.

[2] Benson Latin American Collection, Second International Congress of Historians of the United States and Mexico, Final Program (Austin: University of Texas, 1958).

[3] Ceballos Ramírez. Historiadores.

[4] XVI Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México. “Archivo: Reuniones Anteriores.” University of Texas at Austin, accedido 14 de agosto / accessed 14 August 2022, https://xvireunion.utexas.edu/archivo/

[5] XVI Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México. “Tema de la Reunión.” University of Texas at Austin, accedido 14 de agosto / accessed 14 August 2022, https://xvireunion.utexas.edu/tema-de-la-reunion/

[6] Revista Mexicana de Sociología 26, no. 2 (1964): 596–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/3538621.

[7] Lewis, Archibald R. “The Second International Congress of Historians of the United States and Mexico.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 1, no. 4 (1959): 400–401. http://www.jstor.org/stable/177605.

[8] Sayak Valencia. Capitalismo Gore. España: Melucina, 2010, 124.

[9] ibid., 123.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Banner image courtesy of the Texas General Land Office.