Amy Chazkel’s Laws of Chance explores the rise of a cultural phenomenon that has engrossed the Brazilian imaginary since the turn of the twentieth century: the lottery game jogo do bicho. Its multifaceted analysis ties the “animal game” to the rise of urbanization, consumer capitalism, positivist criminology, and the cash economy in the First Republic (1889-1930). Chazkel focuses on the “gray area” between law criminalizing the popular practice and what actually happened to gambling Cariocas in the streets and in the courtroom. The close-to-the-ground view that she offers reveals that ineffectual criminalization—9 out of 10 cases ended in acquittal—forged a symbiotic relationship between state actors and city dwellers. She intervenes in the study of urban public life by showing that, like sumptuary laws, anti-vice laws were not premodern projects, as scholars have argued, but features central to the governing of cities and the growth of informal economies in Latin America.

Chazkel effectively weaves archival records, photographs, and charts to tell a larger story about bureaucratic efforts to control public spaces and retail economies in modernizing republican Brazil. The game began as a state-sanctioned daily drawing in 1892 to increase the revenue of Baron de Drummond’s zoo. By 1895, the game had “escaped the zoo” as bicheros and banqueiros operated unlicensed lotteries throughout the city that relied on the zoo’s winning animal and corresponding numbers. State officials responded by banning all games of chance in 1896 and inadvertently giving the game its paradoxical status as a criminal offense and widespread cultural phenomenon. The author principally shows that gambling was not only subject to regulation because of its perceived moral degeneracy, but because its revenue fell outside of the state’s purview. These ill-gotten gains flouted the system of concessions the state crafted to control the consumer economy while maintaining a laissez-faire façade.

Chazkel also examines the ways formal legislative codes were redefined in popular legal customs to show how the criminal justice system used the law to repress the growing network of clandestine games in Rio de Janeiro. The fact that the courts acquitted the majority of defendants reveals that judges had great discretionary powers when it came to interpreting the law.

João Batista, the zoo keeper who created jogo do bicho (Image courtesy of Coisas de Florani)

Furthermore, courtroom testimonies expose the law as a pliant tool in the hands of police officers, who used it to line their own pockets and empower themselves through illegal policing methods such as intimidation, blackmail, and the fabrication of evidence. In practice, the legal code meant to suppress games of chance informally taxed them as court fees and fines filled the state’s coffers. The eclectic code also ensured that the game would survive as an extralegal and entrepreneurial aspect of the police profession. Those who suffered in both cases were the ones who, according to Chazkel, could have benefited the most from games of chance: the working poor.

The streets of Rio de Janeiro, ca 1909-1919 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

But the informal lottery became a salient feature of urban street commerce. The monetization of Rio’s financial markets trickled down to the laboring classes, as they developed the need to handle currency, and fueled the expansion of petty gambling. Those who bought and sold jogo do bicho tickets understood that the anonymity the milreis granted them made it harder for authorities to trace their monetary transactions. These exchanges also took cover within the established infrastructure of petty commerce. The open-air markets and small shops Cariocas frequented for everyday necessities provided “the perfect medium in which the jogo do bicho would become institutionalized as a normal yet illegal part of Carioca society.” Chazkel convincingly argues that the state regulated petty gambling because the practice threatened their process of enclosure, which sought to control the use of public spaces and privatize leisure activities, and not because it led to moral decay, as reformists maintained.

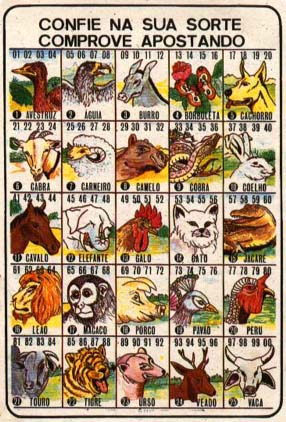

A jogo do bicho ticket (Image courtesy of Coisas de Florani)

Laws of Chance is an engaging and well-written legal and social history that offers a glimpse into the cultural and economic processes that shaped Brazil’s emergence as a modern nation state. One of its greatest achievements is that it forces us to question “the artificial division between jogo and negócio, between play and business, that underlies both historical and contemporary conceptions of social history of the turn of the twentieth century.” Chazkel shows how little playing “the animal game” differed from engaging in legitimate commercial transactions. Rather, the consolidating state created this false dichotomy in its zeal to control all dimensions of consumer commerce. Her historical and theoretical insights will undoubtedly appeal to readers interested in urban studies, informal economies, citizenship, and extralegality in Brazil and Latin America.

You may also like: