Local Memory: A History of Music in Austin is a digital public history project by Brian Jones and Michael Schmidt. We created Local Memory to document less-familiar chapters of Austin’s musical history. Anyone familiar with the culture of the Texas capital likely already knows Willie Nelson, Stevie Ray Vaughn, and the college town’s reputation as a counterculture/roots-music haven. Far from being the obvious culmination of the city’s musical culture, however, those artists and genres changed it. Their musical embrace of the margins largely stood in opposition to the taste, aspirations, and self-image of Austin’s performers and audiences during the previous half century. Surprisingly, it may be the cultural style that took shape before the mid-1960s that proves to be more enduring. The “weird” period that made the city famous ultimately may end as an interlude.

Local Memory’s first two online exhibits point to a forgotten period in Austin’s music history: the years between the onset of the Depression and the beginning of rock and roll. For most listeners, these are likely unfamiliar decades. The 1970s have long dominated Austin’s musical identity, endowing the city with a reputation for non-conformity in a territory of traditionalism.[1] By Ronald Reagan’s second term, the Texas capital was synonymous with outlaws and outsiders, hippies and intellectuals, images evoked by musicians like Nelson, Doug Sahm, and Townes Van Zandt as well as venues like Antone’s, the Soap Creek Saloon, and the Armadillo World Headquarters.

The powerful legacy of the 1970s, however, has obscured the ways that Austin was already a unique musical place before the advent of these cosmic cowboys. Local Memory shows that the city of the Violet Crown already stood apart culturally from Texas’ other major cities during the first half of the twentieth century, albeit in a way remarkably different from its later reputation.

Spanning the period from roughly 1929 to 1955, Local Memory documents two thriving local music scenes that emerged during these years. The first, “Athens on the Colorado,” focuses on dance orchestras at the universities while the second, “The Rise of the Honky Tonks,” covers small vernacular pop bands in working class dance halls and bars. Together, these scenes embodied what made Austin a distinct musical environment in Texas in the decades before the 1970s. It was a city remarkably in sync with the national music industry in a state producing a staggering number of regional innovations.

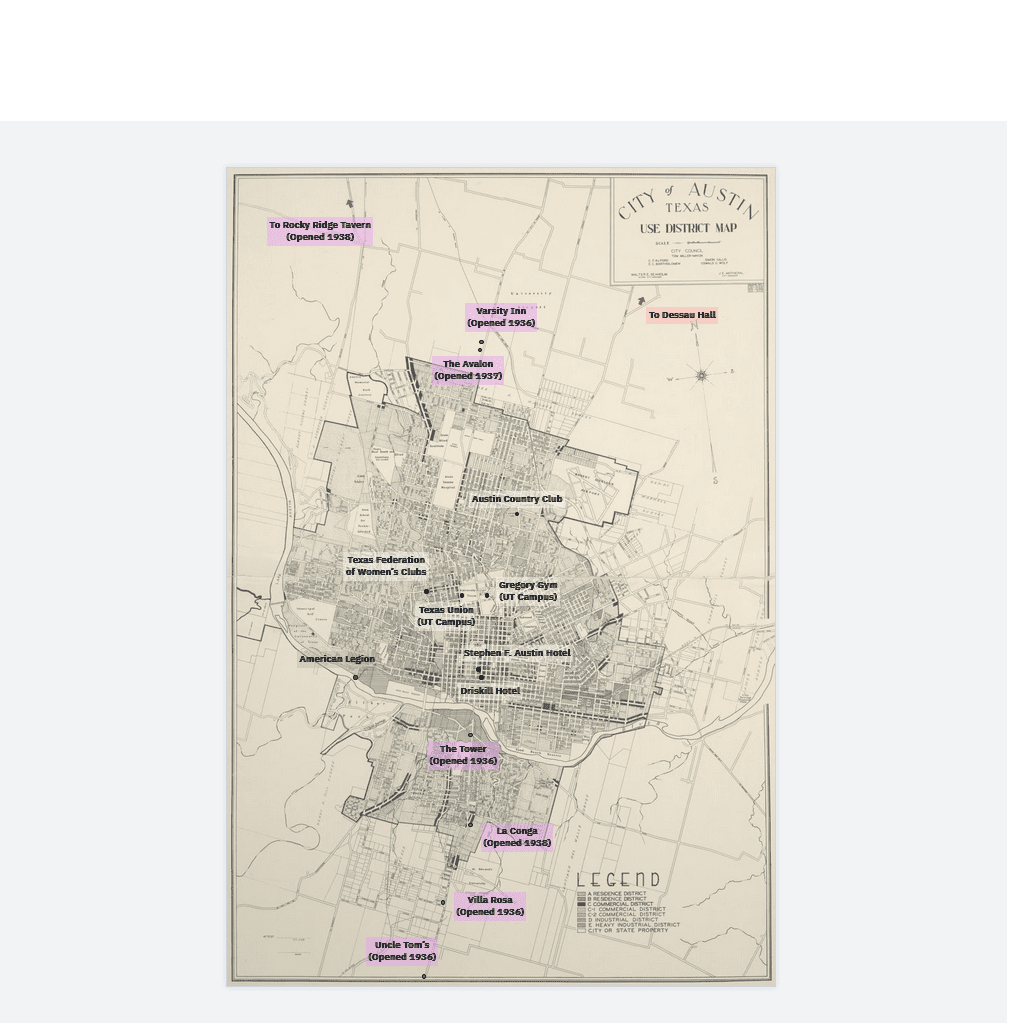

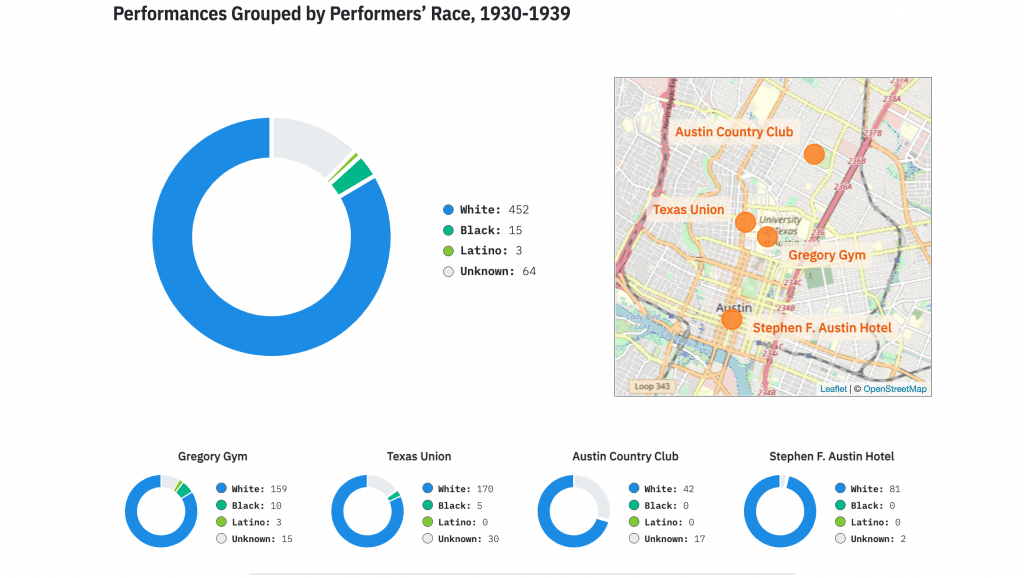

Local Memory tells this story as much with images, maps, graphs, primary documents, oral histories, and music recordings as it does with text. It gives visitors the chance to hear Nash Hernandez discuss his father’s life and band; see the economic disparities between Black and white musicians in Austin through data and graphs; read a 1938 article in the Daily Texan explaining jitterbugs; see the massive growth of Honky Tonks in Austin between 1935 and 1950 through interactive mapping; and explore the look and ambience of UT dances in the 1930s through a photo-essay. Local Memory attempts to create a polyphonic multi-media narrative, one that not only includes the voices of many authors and participants but also does so through many forms of information.

Through Local Memory, we show that if Austin became linked to intellectual, outsider, and roots music in the late twentieth century, it stood out as the most pop-centered city in Texas in the first half of the century. Instead of bucking the trends of the music industry, it was more deeply attuned to them than any other city in the region. At a time when musicians in Dallas, San Antonio, and Houston were creating the distinctive regional styles of Western Swing, Honky Tonk Country, Conjunto, Orquesta music, and early Rock and Roll, Austin did the opposite: it closely followed the broadest forms of national popular music.

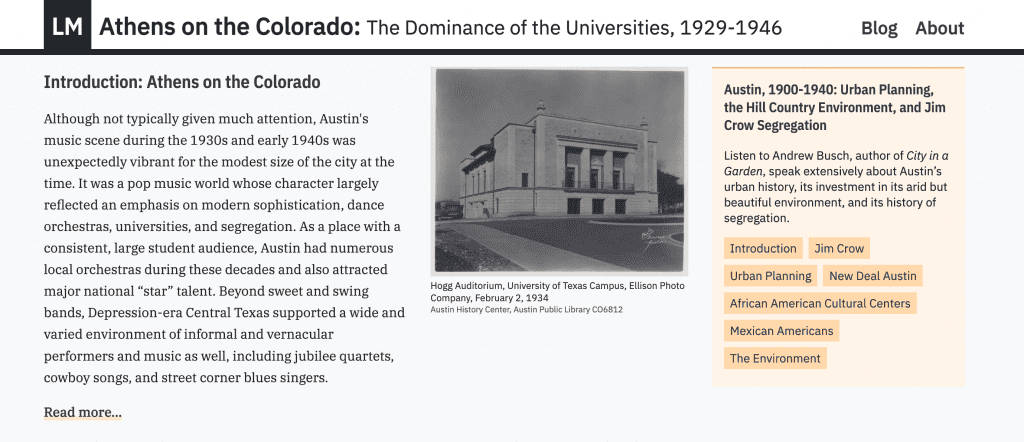

We document this in our exhibit “Athens on the Colorado: The Rise of the Universities,” which examines the music of the 1930s and early 1940s. Although largely forgotten now, Austin was a major hub for Big Band music during the height of its New Deal era popularity. This might seem surprising for a small city that was geographically and culturally far removed from the film industry, recordings studios, and Tin Pan Alley on the East and West Coasts. Austin’s large student population and the growing resources of its colleges, however, helped ensure that its musical life was far more connected to the national music networks than was the case in other Southern and Southwestern towns of its size.

College students dominated Austin’s commercial pop music world throughout the 1930s and early 1940s.[2] This demographic gave the city a unique musical profile in Texas. Although vernacular musics, like fiddle tunes and barrelhouse blues, were certainly present and beloved by their listeners, Austin’s live music world was overwhelmingly characterized by modern dance orchestras. The highly-arranged Swing and “sweet” music of these bands was the hallmark sound of the national industry at the time, the essence of large, corporate, mass-marketed trends. This mainstream orientation distinguished Austin from the music scenes of other Texas cities, where national big band styles were played at dance venues and hotels but existed as a small part of a larger panoply of local styles.

The University of Texas’s growing student body and oil wealth made Austin a consistent destination for now legendary orchestras of the era, including those attached to Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Guy Lombardo, and Dizzy Gillespie. At the same time, the constant appetite for dancing from the students, clubs, and fraternities/sororities created a foundation for the city’s first sustained ecosystem of local orchestras, who largely looked to syndicated radio and the national music industry for inspiration. As a contemporary poll in Billboard demonstrates, the University of Texas had become one of the biggest venues for dance orchestras in the country by the early 1940s. Putting on close to 100 concerts in 1942, UT not only far outpaced all other single institutions of higher education, but it put on around 20% more dances than all the universities in California and Pennsylvania combined.

Although the University of Texas was only one of four colleges in Austin in the 1930s, it commanded the most resources. Its cultural and financial draw were, in fact, considerably greater than the rest of the city as a whole, giving it an outsized influence on Austin’s cultural character in the 1930s. UT students—perhaps because they were young elites self-consciously aware of being in what others considered a backwater—tended to favor the most “sophisticated” styles offered by the popular music industry, not regional music made by non-professional or working-class musicians.[3] Consequently, music in the Texas capital was decidedly more mainstream and outward-looking than any other city in the state during this period.

Austin was bigger than UT. The city’s segregated African American colleges, Samuel Huston and Tillotson, formed a rich, if largely separate, musical environment. Judging from the available sources, Black undergraduates’ popular music taste was similar to their white counterparts—they favored large bands that played the cutting-edge Swing music at the center of the music industry in the second half of the 1930s. Many of region’s African American dance bands, in fact, were linked to local colleges, like the Sam Huston Swingsters and the Prairie View Collegians.

Austin’s place as a major center for African American higher education in the Southwest in the 1930s also attracted some of the most innovative, successful, and respected orchestras in the country to East Austin. The Cotton Club on E. 11th Street, which served as a dance venue for SH and Tillotson students, hosted some of the era’s premier touring bands, including famous musicians like Jimmie Lunceford, Earl Hines, Louis Armstrong, Don Redman, and Lionel Hampton. During a portion of his 1936 tour, Duke Ellington stayed for five days in East Austin, where he had friends amongst the local faculty. Although his band didn’t perform at the Cotton Club, he made numerous appearances at important black civic institutions, including talks and solo/duet performances at Tillotson College, the Samuel Huston College Chapel, the Metropolitan AME Church, and Kealing Middle School.

If Austin’s preference for big band music in the 1930s and early 1940s deeply linked it to the central styles of the Depression-era market, the appearance of new local venues, sounds, and audiences between 1942 and 1950 kept it in sync with contemporary shifts in American musical life. The thrifty pre-war years were a time of market consolidation and an emphasis on styles with wide-appeal, namely pop-oriented big bands and dance music. The post-war music market, on the other hand, fragmented into an array of cutting-edge genres, small record companies, and demo-geographically-specific audiences. This was a moment of radical creativity by the pioneers of Bebop, R&B, modern Country and Western, Chicago electric blues, Conjunto and the independent labels—like Prestige, Atlantic, Starday, Chess, and Ideál—who recorded them.

Local Memory’s second exhibit, “The Wild Side of Life: The Rise of the Honky Tonks, 1940-1950,” traces the growth of the dance halls, musicians, and audiences that fostered this music in Austin. Venues like the Skyline Ballroom and the Victory Grill primarily catered to working class dancers and featured emerging styles of pop music often deemed unsophisticated by culturally-aspiring college students. Breaking with the previous two decades, these spaces and dancers supported a whole new generation of musicians in Austin, dramatically expanding the kinds of music played in public.

The Honky Tonk scene exemplified this departure. By the second half of the 1940s, a rim of rough and tumble venues—memorably called “skull orchards” at the time—lay just beyond Austin’s city limits. These clubs provided a home for the burgeoning sounds of electrified post-war Country music and Western Swing, music that previously had been peripheral to the commercial concert life of the city. Austin’s hinterlands became a magnet for local acts and Country & Western groups from the surrounding counties, including artists like Hank Thompson and Jimmy Heap. These venues were soon plugged into the national circuit. They consistently drew major touring stars from California and the newly minted Country capital in Nashville throughout the 1950s.

From the beginning, these halls were decidedly part of the town and not the gown. Initially fueled by G.I.s on leave from the newly-built Camps Swift and Hood, these threadbare segregated halls became permanent venues for the area’s white working class musicians and audiences. Ultimately, these Honky Tonks, along with analogous clubs in East Austin, created alternative worlds for live music, challenging the power long exerted by the universities over the sounds of the city.

At the same time, the Honky Tonk era maintained an important continuity with the big band scene of the 1930s. Like its predecessor, the post-war music scene kept Austin closely attuned to the larger patterns of the music industry. Again, the city did not revolt against mainstream trends but closely followed them. Ironically, keeping pace with patterns driven by other parts of the country made Austin more closely resemble the rest of Texas, which had long fostered a range of innovative regional styles.

It was only in the late 1960s and early 1970s that Austin began to turn itself into a haven for less commercial, more progressive, counter-cultural music. That outsider identity is now likely in retreat, however. As the city becomes increasingly expensive—rents rose a remarkable 40% in 2021[4]—the relatively cheap and arty environment that undergirded Doug Sahm’s “Groover’s Paradise” and Richard Linklater’s Slacker is disappearing (some feel that this side of Austin began to decline as early as the 1990s). For all its future-oriented claims, the tech industry has seemingly returned Austin to the past, renovating and flipping the capital into a big city version of the elite mainstream culture of its interwar period.

[1] For an example of how Austin’s identity is deeply associated with the music and culture of the 1970s, see John T. Davis’s Austin Monthly article “How the 1970s defined Austin.” https://www.austinmonthly.com/how-the-1970s-defined-austin/. The major exceptions to this timeline are the early folk career of Janis Joplin and the psychedelic scene revolving around the 13th Floor Elevators and the Vulcan Gas Company. These counter-examples comfortably fit as predecessors to the ethos and style of what came after them, however.

[2] It should be pointed out that the cultural power in Austin of University of Texas students during this period magnified the effect of the racist ethos of UT-affiliated minstrel shows and blackface performances. See, for example Dr. Edmund Gordon’s Texas Cowboy Pavilion stop on the Racial Geography Tour. https://racialgeographytour.org/tour-stop/texas-cowboy-pavilion/

[3] For example, Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys—whose Western Swing was massively popular with working class audiences in Texas, California, and the Southwest during this period—never played on campus.

[4] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/01/30/rent-inflation-housing/

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.