From the Editors: Not Even Past Second Editions update and republish some of our most important and widely read articles. Since the original publication of this article in April 2020, A Black Women’s History of the United States, authored by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross, has enjoyed remarkable success including numerous accolades. It was nominated for a 2021 NAACP Image Award: Outstanding Literary Work – Non-Fiction; was recognized as one of The Best Black History Books of 2020 by the African American Intellectual History Society and was a nominee for Goodreads Best of History and Biography 2020. The book was one of Kirkus Best Books of 2020: Black Life in America as well as a Kirkus Best-Big Picture History Books of 2020. Most recently, the Organization of American Historians recognized A Black Women’s History of the United States with an Honorable Mention for the Darlene Clark Hine Award for best book in African American women’s and gender history. The citation noted that “this comprehensive analysis of African American women from their African precolonial beginnings to the millennium’s first years will soon serve as the definitive work on Black women and their foundational contributions to the history of the United States.” Finally, the book was just awarded the Susan Koppelman award for the best anthology, multi-authored, or edited book in feminist studies in popular and American culture by the Popular Culture Association. A Black Women’s History of the United States will be translated into Chinese and published by Horizon Press in 2023. We congratulate Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross on the incredible success of their book and are honored to republish a second edition of their article below.

A few years ago, we were approached by Beacon Press to write a history of Black women in the United States. We felt both honored and overwhelmed by the task. Before we began, we needed to first take a survey of the field and understand our place in it.

The field of Black women’s history has generated a plethora of scholarship for more than a century. Anna Julia Cooper, the first African American woman to receive her PhD in History and Romance Languages (University of Paris, the Sorbonne, 1925) was part of a small group of early historians. Cooper is widely regarded as one of the first writers of Black feminist thought.[1] In the 1940s several Black women received their PhDs in History including Marion Thompson Wright who was the first to earn a PhD in the United States (Columbia University). Over the last fifty years, female scholars have published numerous works on Black women including anthologies, encyclopedias, primary document readers, biographies, and thematic studies of women in the diaspora.

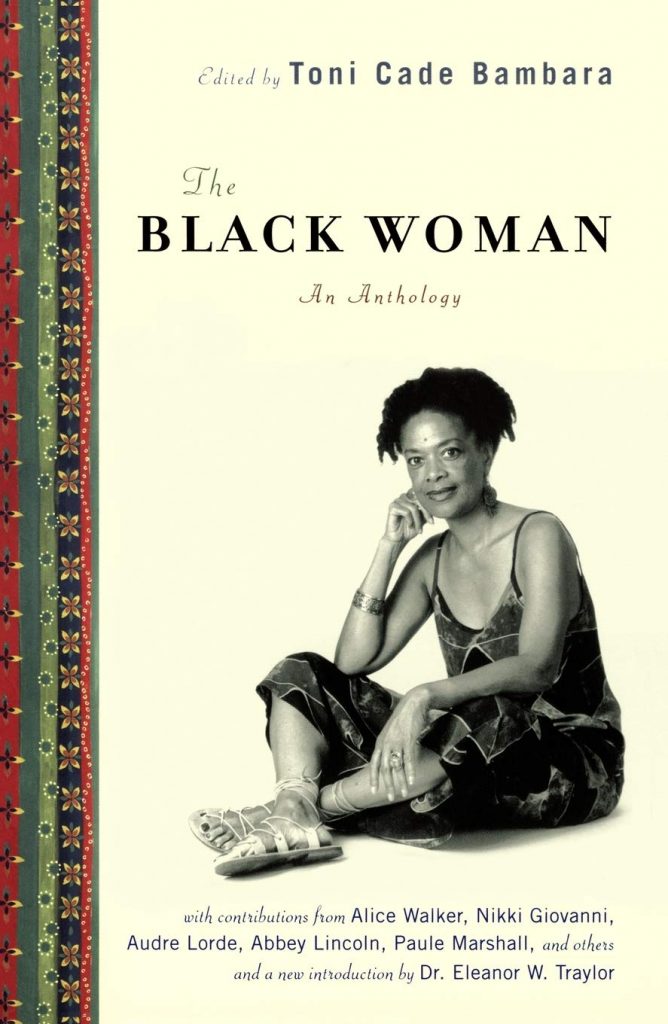

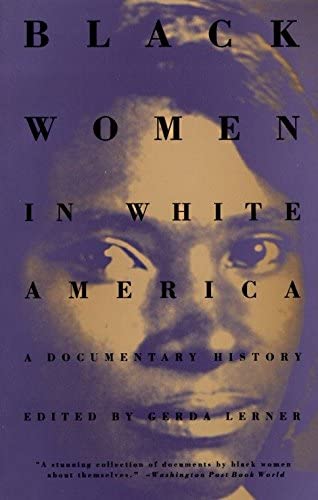

Black women’s history emerged as a unique field in the early 1970s, in the heart of the women’s rights movement, at a time when colleges and universities established women’s studies programs and courses. In 1970, Toni Cade published the anthology, The Black Woman, as one of the first seminal collections of writings about Black women.[2] Two years later, Gerda Lerner released a primary document reader, Black Women in White America, a book filled with evidence of Black women’s contributions to American history. Adopted for classroom use, Lerner’s book served as the first compilation of document driven histories of Black women in America. Following her, historians Sharon Harley and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn published The Afro-American Woman: Struggles & Images (1978).[3] These volumes served as starting points for the field.

Many of these early writers were activists in the classroom and in their communities. The scholarship they produced in the 1970s evolved in a period of activism where women fought to be recognized in society, at colleges and universities, and in historical scholarship. Such activism, particularly among Black lesbian women who attended the Combahee River Collective in 1974, forced mainstream scholars to consider the diversity of Black women’s experiences in America. Women at Combahee illustrated how their experiences intersected along multiple categories including race, class, and sexuality, offering experiences that Kimberlee Crenshaw a decade later called “intersectionality.”[4] They also prompted a proliferation of texts that addressed how Black women lived, worked, and loved at these intersections.

The 1980s marked the first significant increase in publications in the field of Black women’s history. So, it is not a surprise that the nascent field welcomed Angela Davis’s, Women, Race, & Class (1981) as writers began to consider the dynamic nature of Black womanhood, again, prior to having a term to describe it. Like their foremothers a decade earlier, writers in this decade also published primary document anthologies such as Dorothy Sterling’s We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century (1984).

The eighties also produced books that provided overviews of Black women’s experiences such as Paula Giddings’s groundbreaking study, When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America (1984). A year later, Deborah Gray White answered Angela Davis’s call to explore the experiences of enslaved women with Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (1985) and Jacqueline Jones examined Black women’s experience with unpaid and paid work in Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present (1985).

By the 1990s the field had been in full force for about twenty years with a growing national organization. The Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH), founded in 1979, became the professional and professionalizing steward of the field. Pioneering historians of the previous two decades mentored students and kept publishing work in the field. Darlene Clark Hine, an institution building scholar, helped push the field in several directions by publishing books, reference works, and anthologies.[5] After decades of work, she would receive recognition from President Barack Obama in 2013 with the National Humanities Medal. Along with Giddings’ When and Where I Enter in the 1980s, Hine and Kathleen Thompson’s A Shining Thread of Hope: The History of Black Women in America (1998) served as foundational texts for the field for next two decades. These books shaped and fueled an abundance of scholarship in the nineties, including work by the founders of ABWH and others who pioneered defining theoretical approaches to Black women’s history and confirmed that we have a clear canon. These included but were not limited to Hines’ “culture of dissemblance,” Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s “politics of respectability,” and Ula Y. Taylor’s “community feminism,” among others.[6]

Scholarship from the turn of the century in 2000 until today has witnessed a dynamic boom as three generations of historians are publishing work on a variety of themes. We are at a profound moment where many of the founders of Black Women’s History are still alive and continue to publish books, articles, and anthologies. These pioneers are able to witness, shape, and support multiple generations of historians. This also means that we have a pipeline of scholars and scholarship that is building on these foundations and creating new histories that bring Black women into all aspects of American and diasporic history. The 2015 Cross Generational Dialogues in Black Women’s History conference at Michigan State University brought these scholars together to pay homage to those who created the field and those who are the future of it. Scholars of the first generation of Black women historians sent their students out to produce more work for this field. They offered studies of Black women and slavery, reconstruction, convict leasing, civil rights, Black power, and a host of other topics and time periods.

A number of those founding scholars, as well as their students, generously read and advised us on how we might proceed in writing a newer survey. In 2019, we held a historic manuscript workshop at Rutgers University. For the better part of day, ten Black women historians from across the country, met to read and critique early drafts and outlines. It was an extraordinary event that compelled us to find meaningful ways to build on vital existing scholarship, while adding new histories and experiences into the historical record. We include everyday and elite Black women, enslaved and free, artists and activists, poets and athletes, Black queer women, politicians and incarcerated women. Our work, A Black Woman’s History of the United States, serves as the current generation’s study even as we have paid homage to the scholars who paved the way for us. Our hope is that this contribution will make an impact on this field and the wider reading audience.

LISTEN to Berry and Gross discuss their work in an interview by UT History graduate student, Tiana Wilson, here on the podcast “Cite Black Women”.

And read more about Tiana Wilson’s interview on the “Cite Black Women” blog.

LISTEN to Berry and Gross discuss their work and the legacies of Black women’s activism, resistance, and entrepreneurship with journalists Maria Hinojosa and Julio Ricardo Varela on the In The Thick podcast.

LISTEN to Berry and Gross profile history-making Black women on WHYY Radio Times.

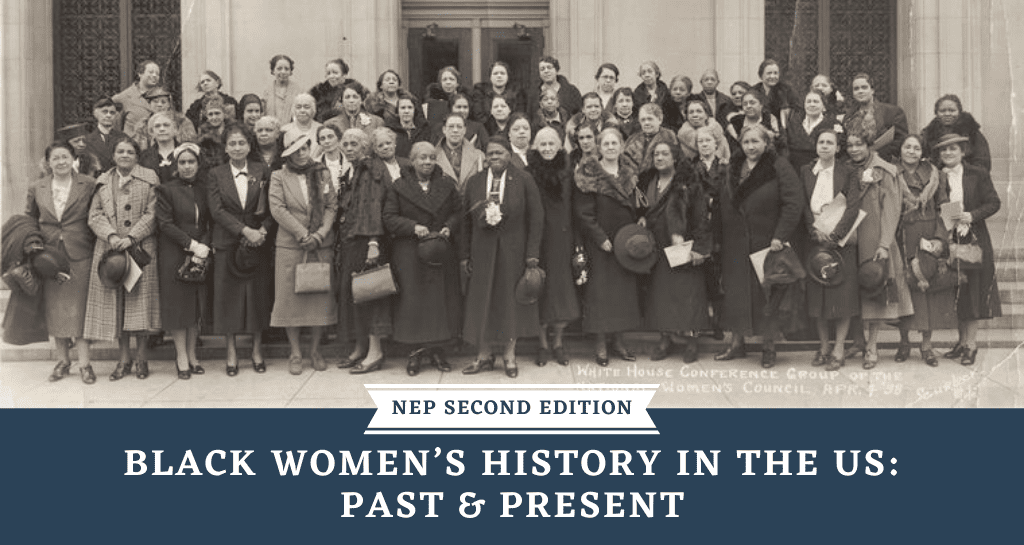

Banner image credit: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “White House Conference Group of the National Women’s Council (Mary McLeod Bethune, center; Mary Church Terrell, to her right)” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1938.

[1] Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South: By A Black Woman of the South (Xenia, Ohio: The Aldine Printing House, 1892).

[2] Toni Cade, ed., The Black Woman: An Anthology (New York: New American Library, 1970).

[3] Dorothy Porter, “Forward,” in Sharon Harley and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, eds., The Afro-American Woman: Struggles & Images (1978. Reprint. Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1997), viii.

[4] Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989, Article 8. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

[5] Selected single authored and co-authored books by Darlene Clark Hine include Black Women in White: Racial Conflict and Cooperation in the Nursing Profession, 1890-1950 (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1989); Hine Sight: Black Women and the Re-Construction of American History (New York: Carlson Publishing, 1994); and A Shining Thread of Hope: A History of Black Women in America (New York: Broadway Books, 1998). Edited and co-edited reference works and anthologies include Black Women in United States History: 16 volumes, plus the guide (New York: Carlson Publishing, 1990); Black Women in America (1994; Reprint. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); We Specialize in the Wholly Impossible (1995); and Beyond Bondage: Free Women of Color in the Americas (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004).

[6] Darlene Clark Hine, “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West,” Signs 14, no. 4 (Summer 1989): 912-20; Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993); Ula Y. Taylor, The Veiled Garvey: The Life and Times of Amy Jacques Garvey (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002).