If Poppaea, the purported owner of the grand Roman villa that has come to light near Pompeii, were to walk into her slaves’ quarters today, she would think the gods had enchanted it. What are these banks of red flashing lights and strangely-dressed men and women manipulating words and pictures on magical tablets? It’s the Oplontis Project team, using digital technology to reanimate her Villa, which was buried in ash on August 24, AD 79, when the Mount Vesuvius volcano erupted near Pompeii.

Oplontis Villa A, north façade and garden after replanting in 2010. Photo by John Clarke. ©The Oplontis Project

Italian excavations between 1964 and 1984 uncovered 99 of the villa’s spaces, including over forty exquisitely-decorated rooms, four large gardens, and a 61-meter swimming pool. After a hiatus of more than 20 years and on the invitation of the Italian Ministry of Culture, I assembled a team of experts to excavate, study, and publish Poppaea’s Villa (officially known as Villa A at Oplontis, Torre Annunziata, Italy), a UNESCO World Heritage site. The high-speed internet and multiple computers that would astonish Poppaea are only a small part of the arsenal of digital technologies that are bringing her villa to life.

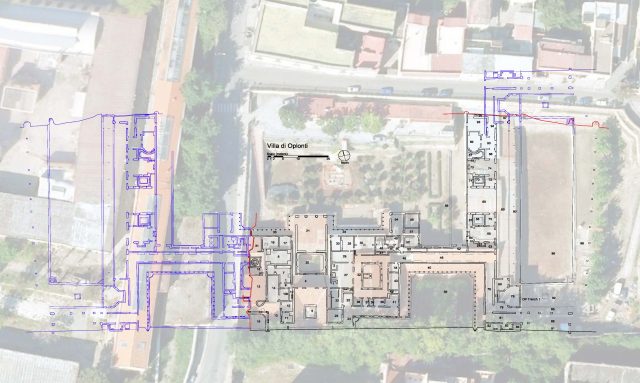

Aerial view of site with superimposed plan of actual and hypothetical remains. Drawing Timothy Liddell. ©The Oplontis Project

Given the many unanswered questions about what had been excavated, the Oplontis Project chose not to attempt to bring to light the estimated forty rooms that still remain under a nearby military complex, but rather to study fully what was there. This meant conducting the first excavations beneath the AD 79 level to learn about earlier phases of the villa and to carry out geological surveys to understand its relation to the surrounding land- and sea-scape. It also meant dealing with thousands of orphaned fragments, combing archives to track the procedures used to recreate the villa, and analyzing the chemistry of everything from ancient carbonized wood, to the pigments used in the frescoes, to the marble used throughout the Villa.

To address these challenges in the most efficient way, we adopted three digital strategies: the born-digital e-book for publication; a flexible database to collect and share resources; and a navigable 3D model to record the actual and reconstructed states of the Villa.

In light of the limitations of print publication, we chose the most successful scholarly publisher of digital e-books, the American Council of Learned Societies Humanities E-book series. Their ambitious e-books typically have excellent finding tools and hyperlinks to a myriad of electronic media, including archive repositories, databases, and films. Our book, Oplontis: Villa A (“Of Poppaea”) at Torre Annunziata, Italy is now available for free on-line.

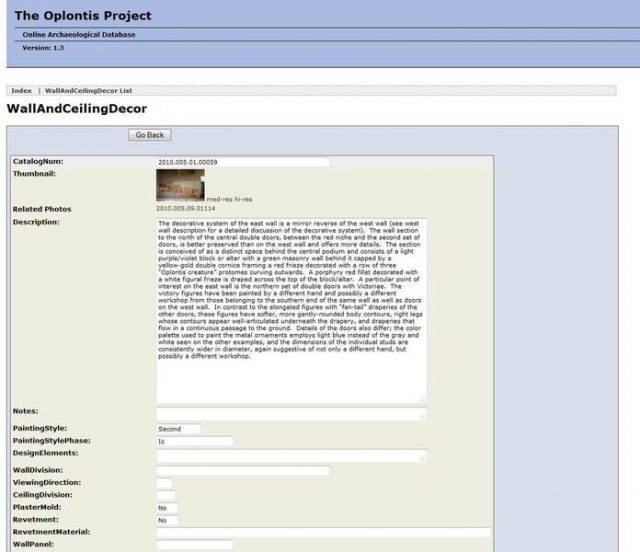

The Oplontis Project database developed parallel to the ACLS e-book; indeed some of the contributors to the e-book began work on their chapters by building their part of the database. For this reason it includes all of the categories of research we are doing, including the decoration of all surfaces, the architecture, excavations, archival materials, and photographs. In this sample page from category 1, Wall and Ceiling Decorations, we see the east wall of the atrium, the top part of the catalogue description, written by Regina Gee, and a thumbnail image of the wall.

Clicking on the thumbnail we get a screen showing the actual-state photograph taken by project photographer Paul Bardagjy in 2009. From here we can link to scores of archival photographs of this wall, including details of the wall when it was in better shape.

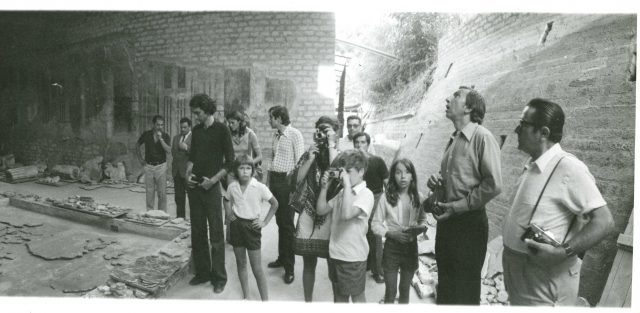

One of the archival photos linked to this wall recently came into our hands from a private collector in the town of Torre Annunziata. It shows what the atrium looked like when Princess Margaret of England visited the Villa in 1973—years before it was open to the public.

Oplontis, atrium 5. Visit of Princess Margaret and entourage 14 August 1973. Courtesy the Vincenzo Marasco Archive. ©The Oplontis Project

Notice that the Princess is shooting photos—and also notice the leftover fragments lying on the floor. A yet earlier photograph, from the Wilhelmina Jashemski Archive, shows what the wall behind the royal group looked like at the time of excavation, around 1968: it was in a state of collapse. The wall paintings a tourist sees today were literally salvaged from the debris, consolidated with reinforced concrete backings, and re-hung on a wall made from modern materials.

Oplontis, atrium 5, east wall. Photo the Wilhelmina Jashemski Archive, 1968_45_24. © The University of Maryland

As this historical photo shows, when excavations began on the west wall of the atrium in 1966, it was miraculously standing to the level of the architrave (Fig. 7).

Oplontis, atrium 5, west wall, at beginning of excavations. Photo courtesy the Soprintendenza Archaeologica di Pompei, De Francisis Archive, dia 9.392

After reconstruction, it was clear that the top part of this wall had succumbed to the blast of the pyoclastic flow, displacing fragments of its upper zone. When we located the fragments piled on the floors of several storage areas (transformed today into our laboratories), we had the basis for reconstructing an Ionic second story, which you can see below.

Oplontis, atrium 5, west wall. Reconstruction by Martin Blazeby, King’s Vizualisation Lab. © King’s College London

As one sees it today, the modern roof is some three meters too low. The 3D model allows us to reconstruct the interior of this and all the other spaces of the Villa, finding homes for the many fragments of painted and stucco decoration (over 3,000 in all) that were left over when funds ran out.

Not only have we been able to put fresco fragments into their context through digital means, we have also reconstructed whole rooms. A case in point is the transformation of a seemingly featureless space into the most lavishly decorated reception room in the Villa.

The process of reconstructing room 78 started with my discovery of a cryptic note in the excavation daybooks for 1974 mentioning that excavators had found a series of impressions of wood panels in the hardened volcanic ash. This is a kind of wall revetment never before attested in antiquity. What of the floors and wainscoting, stripped of their marble in antiquity? Simon Barker closely studied tiny fragments of marble residue, identifying the range of expensive marbles used in that one space and reconstructing the patterns on the floor and walls. Architect Timothy Liddell put all of this data into a 3D environment to provide a stunning—and unprecedented—visualization of this opulent room, a unique testimony to the tastes of super-wealthy patrons like Poppaea.

Oplontis, diaeta 78. Digital reconstruction. Timothy Liddell and Simon Barker. ©The Oplontis Project

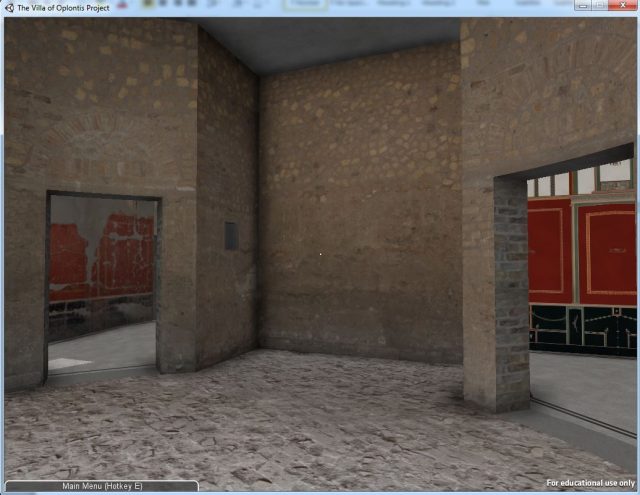

All of these room reconstructions are in the process of being integrated into a 3D model of the whole site. In its current beta version, the 3D model gives a user unlimited access to the entire 100 x 200 meter site, the same access available to the Oplontis Project team under the terms of its collaboration with the Archaeological Superintendency of Pompeii.

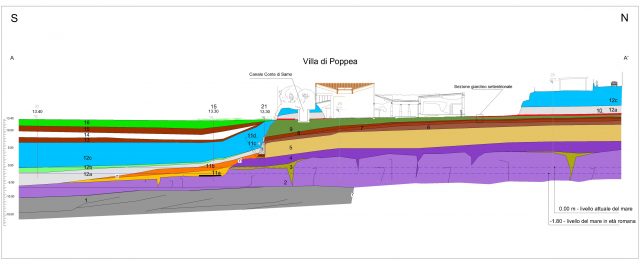

Finally, exciting new geological research has revealed the ancient setting of the Villa. There was one clue, partially explored in the Oplontis Project’s first excavation: a stairway descending from the slaves’ quarters to a tunnel, filled with hardened volcanic ash. Using Ground-Penetrating-Radar, we found anomalies on the south of the Sarno Canal suggesting that the tunnel ended in a stairway leading down some 9 meters. But it was not until geologist Giovanni Di Maio sunk a series of cores between 15 and 30 meters below the modern surface, that we knew that the Villa stood perched on a 14-meter cliff above its own private harbor. In the section, we see that the volcanic material to the north of the Villa, beneath the modern town, also accumulated over the parts pushed over the cliff by the force of the pyroclastic flows.

Oplontis, Villa A. North-south section showing Villa on cliff above sea. Digital rendering. ©Giovanni Di Maio

The remains of other Roman villas that Di Maio has documented remind us of Strabo’s description of the villas and cultivated estates that stretched along the entire rim of the Bay of Naples like one continuous city.

Several features distinguish our 3D model from other similar archaeological initiatives. Since it is based on a first-person shooter gaming engine, Unity©, the user can navigate every space at will—unlike the determined paths of most models. The user can also toggle between actual and restored states, change the lighting systems, and meet other avatars. Most important for its use as a scholarly resource is the fact that by pressing the “Query” button, a researcher can directly access the database for the feature on the screen—whether a wall painting, or the finds in one of our 20 trenches, or the results of isotopic analysis of the marble of one of the 19 sculptures found in the gardens.

Oplontis, view southeast corner of pool and diaeta 78, with several sculptures reset in place. Photo Stanley Jashemski 1978_2_27. ©The Wilhelmina Jashemski Archive, The University of Maryland

The original excavations of Villa A at Torre Annunziata aimed to make it into a living museum that the public could visit. This meant creating a new building that looked ancient. Walls had to be rebuilt and colonnades had to be reconstructed to support modern concrete beams, new tile roofs, and reconsolidated fresco fragments. In the process of building this living museum, the pieces of the puzzle that didn’t fit were simply ignored. Today, with digital means, we have put many of those puzzle-pieces back into the Villa.

The 3D model, linked with the database will allow us, and future generations, to find material easily by clicking on find-spots; scholars will be able to share in our work and even add to the information in our database. The model complements the e- book and because the ACLS has graciously offered to make the Oplontis Project publications open access, scholars and laypersons worldwide can benefit from the work of our 42 contributors, coming from wide range of scientific and humanistic disciplines.

A longer version of this article was originally published in Apollo: The International Art Magazine (February 2014), 48-53.

John R. Clarke and Nayla K. Muntasser, Oplontis: Villa A (“Of Poppaea”) at Torre Annunziata, Italy (e-book)

Top image: Oplontis, oecus 15, reconstruction of west wall from fragments, overlay on portion of east wall. Reconstruction by Timothy Liddell. ©The Oplontis Project