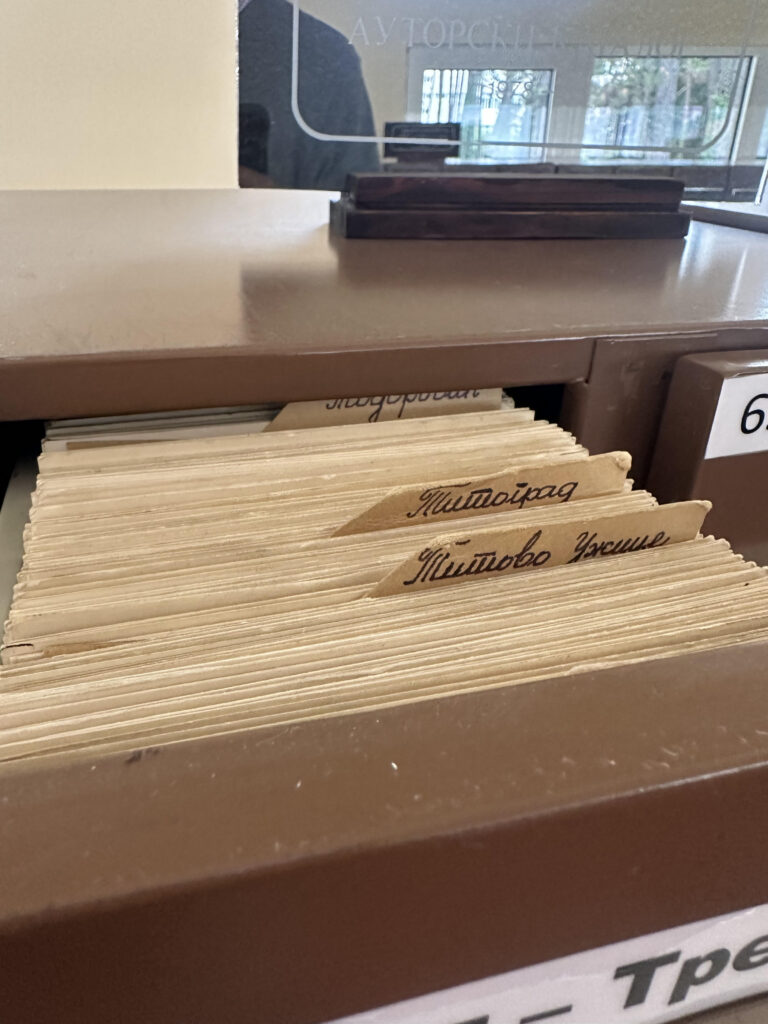

As people in the past lived out their lives, did they realize the ways in which they would help create the archive of the future? Did the owner of a particular stack of newspapers deliberately label it “Borba Zagreb 1949” to preserve a record of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia’s official gazette from that year, or was the note atop the pile simply an act of routine organization? How does an archive—filled with countless documents chronicling the lives of so many—capture the beauty and complexity of the human experience? These questions swirled in my mind as I explored the halls of the Đurđe Crnojević National Library of Montenegro, or the Nacionalna biblioteka Crne Gore, “Đurđe Crnojević,” this past summer, an experience I later reflected upon in Notes from the Field: Crnojević’s Shelves.

In a short time, the library’s massive collection and meticulously cataloged documents led me to experience firsthand the reason why an archive can become such a cherished part of a people’s cultural identity. At the Đurđe Crnojević National Library, it was the always friendly, knowledgeable, and extraordinarily diligent curators of the collections who formed the heart of the historization process, shaping the archive as a reflection of collective lived experience. My time in Montenegro also taught me the significance an archive plays preserving and defending a people’s history—serving as a fortress wall, safeguarding it against forces that would see their history either destroyed or delegitimized.

The bloody history of archives in former Yugoslavia

A little over 30 years ago, in a territory once unified as the Socialist Federated Republic of Yugoslavia, a devastating wave of violence swept across the region. Nationalist politicians and warmongers ignited a series of wars fueled by ethnic and religious divisions, ultimately leading to the country’s destruction. During these Yugoslav Wars of Succession, nationalist state-building projects sought to create ethnically “pure” nation states, resulting in widespread violence, ethnic cleansing, and the delegitimization of history. This is on clear display in the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. During the three-and-a-half-year long siege of the country’s capital, Sarajevo, Serbian-backed forces relentlessly terrorized the civilian population, attacking the city with artillery and sniper fire. Their goal was to force the coalition of Bosnian Muslim and Croat forces to surrender the city.

On the night of September 25, 1992, Bosnian Serb guns deliberately fired incendiary shells upon the National Library of Bosnia, affectionately known as the Vijećnica, with the intent to destroy a rich archive of the Bosnian peoples. A former city hall built in the time of the Austro-Hungarian empire, the Moorish-style building housed over 1,500,000 volumes and 150,000 old manuscripts, all of which were devoured by the flames. Naza Tanović-Miller, a university professor who wrote about her experiences during the siege, described the scene of horror as the cultural symbol of her people was destroyed, “Our treasure was burning. The Bosnian past was burning… The shelling never stopped for three days. Burned pages and pieces of paper were flying in the front and back of our house… I collected a few ashes and held them gently in my hand. All of Sarajevo cried.”

Coming to Montenegro

Thirty-two years later, at the start of summer 2024, I found myself preparing to explore a key regional archive for the first time in my academic career. While I am no stranger to the Balkans—I have lived and studied in the territory of former Yugoslavia several times before—this was my first visit to Montenegro. When in the Balkans, however, the memory of the wars are never far from my mind, especially the story of the Vijećnica and its brutal destruction.

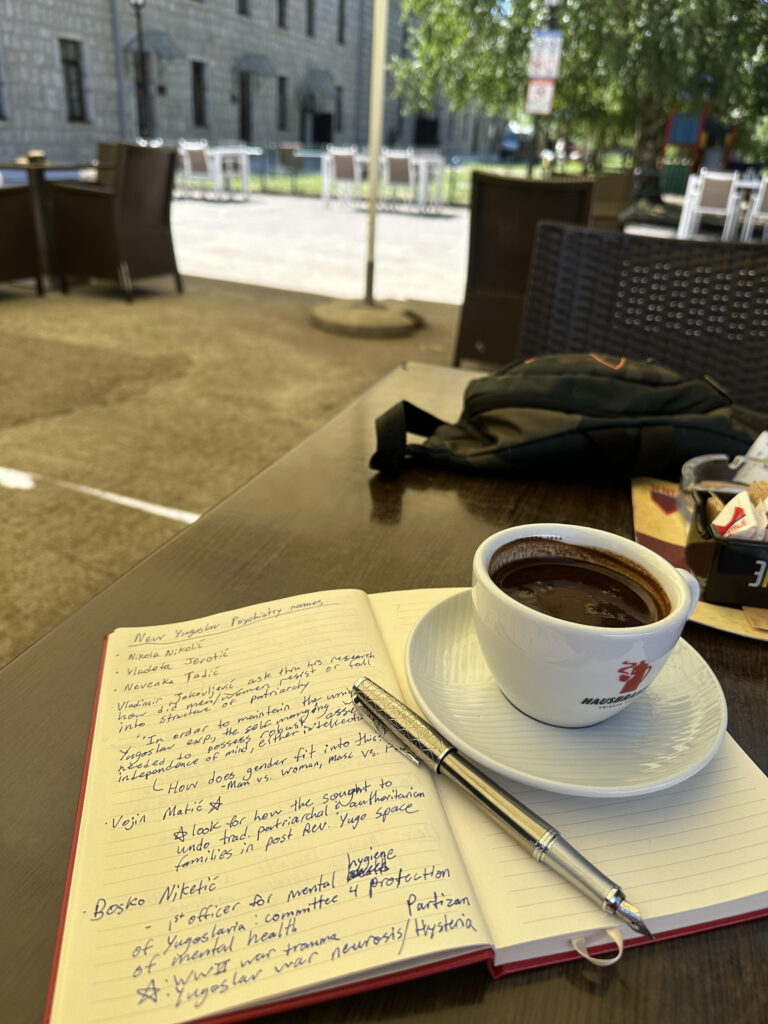

My journey into the Montenegrin archives emerged from a research project I had been developing in the spring of 2024. The project’s central question examines how Yugoslav perception of gender—amongst both women and men—changed after Tito’s Partisans’ victory in World War II. Specifically, I am investigating how the socialist revolution changed wider views of gender and gender roles in the newly formed socialist Yugoslavia. In what ways did the socialist revolution inspire hope and progressive change for women, even if those changes were eventually hindered by patriarchal paternalism?

My research led me to Ana Antić’s fascinating article entitled “The New Socialist Citizen and ‘Forgetting’ Authoritarianism”, which analyzed how new schools of psychiatric thought and practice in socialist Yugoslavia sought to apply the ideals of the revolution by expanding access to mental health services. Antić’s work, in turn, led me to the writings of various Yugoslav psychologists who worked with Partisan veterans afflicted with what they coined, “Partisan neurosis”—a form of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that afflicted soldiers after the war. I stumbled upon a fascinating discussion about these post-war psychologists, who implemented new psychoanalytical techniques designed to bring about a new Yugoslav socialism, including its goal of decolonization and solidarity within the Non-Aligned Movement solidarity.

However, there was a crucial gap in this literature. I discovered that no one seemed to analyze the complex dynamics of gender in this post-war, post-revolutionary socialist period. I felt excited realizing that my project could fit in the discussion by bringing a gendered analysis to the same discussions of this time period between 1945 and 1960. But in order to fill this gap and conduct a meaningful gender analysis, I needed firsthand access to the original sources and writings of these Yugoslav doctors and socialist theorists.

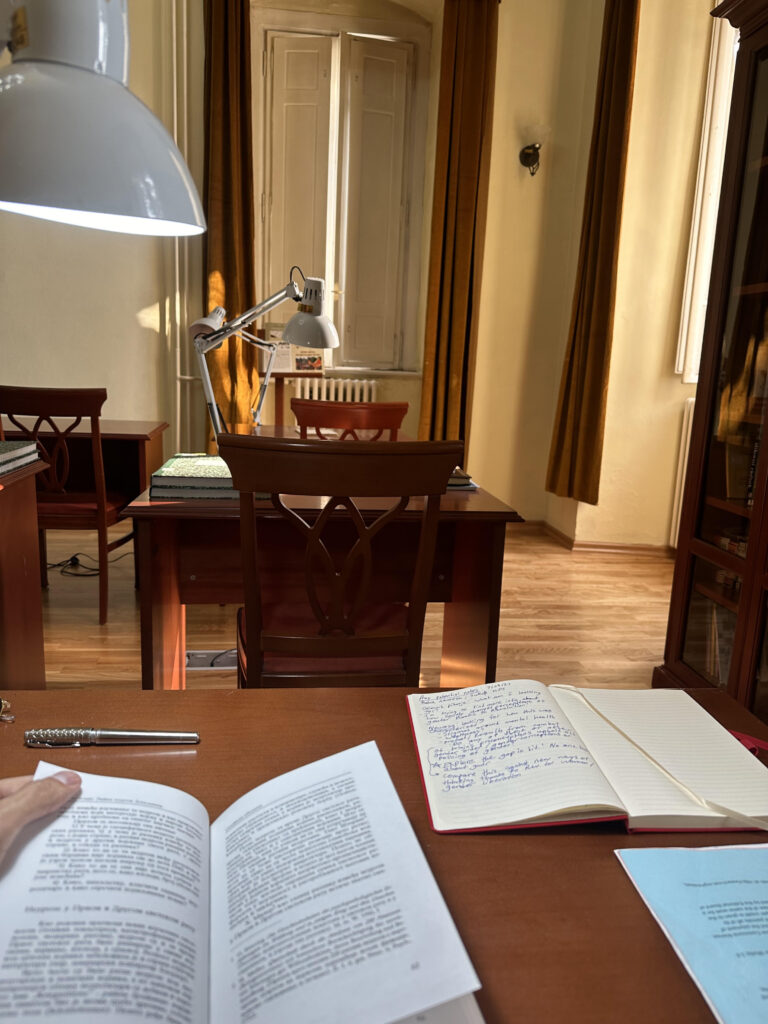

Exploring the Archive

Spending time in Montenegro, you quickly become aware of the long struggle of its people to preserve their political and cultural independence. In 2006, Montenegro rallied its domestic and diasporic population to vote in a referendum for independence from the state union of Serbia and Montenegro, which had succeeded Yugoslavia. With a narrow 55.5% majority, they won their independence. However, recent development—particularly in Cetinje, home to both the National Library and Archives of Montenegro—have recently renewed calls to action to defend their sovereignty and cultural identity. These calls to action stem from concerns over potential absorption into a ‘Greater Serbian’ sphere of influence, highlighting the ongoing tension between national self-determination and regional political dynamics.

Between 2020 to 2022, protests erupted across Montenegro in response to the government announcing changes to citizenship, which the opposition claimed would enable the creeping ‘Serbianization’ of the country. Protests were refueled in August 2021 over what Dr. Šušanj described as the subtle colonization of Montenegro by the Serbian Orthodox Church, one that intended to eliminate the existence of a separate Montenegrin ethnic and religious identity. Protesters resisted the enthronement of the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitan Joanikije Mićović by setting up boulder and tire barricades in and around Cetinje in an attempt to block the ceremony from taking place. Youth leaders like Peđa Vušurović argued that by allowing the Serbian Orthodox Church to strengthen its grip around cherished Montenegrin historical sights—such as St. Peter’s chair in the Cetinje Monastery, a symbol of Montenegrin spiritual, state, and national freedom—risked subsuming Montenegrin identity and history within a larger sphere of Serbian world.

Images of protesters clashing with police, strangled by clouds of tear gas as their tire barricades burned behind them, taught me a great deal about the people of Montenegro. This rang especially true in my mind as the scars from the 1990s remain ever present, and the scourge of divisive nationalism still runs rampant through the other Ex-Yugoslav states. I will never forget the feeling in the pit of my stomach in June 2021 when I saw a banner celebrating convicted war criminal Ratko Mladić, the “Butcher of Bosnia”, as a Serbian hero draped over the Novi Sad football stadium.

Even today, Montenegro celebrates its anti-fascist past. In contrast to other former Yugoslav states, like Croatia, which have explicitly worked to denounce and destroy their connections to Yugoslavia and it’s anti-fascist monuments, history, and in some cases cemeteries, the opposite is true in Cetinje. In 2024, the country commemorated the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Cetinje from fascist occupation. Near the main square, a large banner honored female Partisan fighters from the 1st Battalion of the 4th Proletarian Brigade, and the famous Orden Grada Heroja, or the Order of the People’s Hero. This prestigious Yugoslav military decoration recognized acts of bravery during both peace and wartime, designating recipients as “people’s heroes” of Yugoslavia. Throughout my time in Montenegro, I encountered numerous Yugoslav plaques celebrating local heroes in every city and neighborhood, and statues honoring the anti-fascist resistance movement and its icons were consistently cared for and preserved. Some, as in the case of famous martyr Ljubo Čupić in the city of Nikšić, still had fresh flowers woven into the statue.

Moving forward

By the end of my time in Cetinje, I realized that my original research goals had not been fully met. I had expected to find a more overt discussion of socialist ideals with these new Yugoslav psychologists. In reality, the picture that emerged was slightly different. However, thanks to the many lessons taught to me by Crnojević’s library and the resilient people of Montenegro, I now have a new direction with which to progress my project on gender in the post-war socialist space. With the addition of various literature sources, I plan to use what I found in the archives to further explore my questions. I also hope to return to Montenegro many more times in the years to come.

David Castillo is a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, focusing on the former communist Yugoslavia and its successor states. His research explores the links between inter-communal violence, toxic masculinity, gender dynamics, propaganda, and mass manipulation. With academic foundations from the University of Texas at El Paso and Indiana University, David combines cultural history with international politics. Drawing from his experience in the region, he aims to compare post-Yugoslav masculinity shaped by the 1990s wars with Chicano/a/e ‘Machismo’ in Mexican-American borderlands, investigating how violence becomes integral to both identities.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.