In Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean, Kristen Block explores the role of religious doctrines as rational, strategic discourses in the seventeenth-century Caribbean. Certainly, Christianity shaped inter-imperial diplomacy, economic projects, and “national” identities. Yet, Block argues that powerless and disenfranchised individuals embraced or denied religious doctrines at will, in order to obtain advantageous political outcomes. Block illustrates that religion was not only a force of social inclusion and exclusion, but also a persuasive tool that allowed ordinary people to shape allegiances, perform Catholic or Protestant identities, and pursue justice and opportunity.

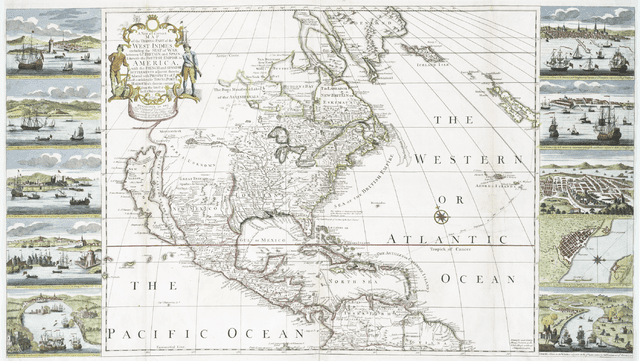

The book illustrates the instrumentality of lived religions by focusing on the personal stories of people of African descent and lower-class Europeans. The first part of the book traces the life of Isabel Criolla, a runaway slave who employed the Spanish legal system and religious discourse in Cartagena of the Indies in order to escape her mistress’ cruelty in 1639. The second part explores how Nicolas Burundel, a French servant and Calvinist, embraced Catholicism as a tactic for navigating Spanish institutions in 1652. Henry Whistler—a British seaman in the Cromwellian era—is the focus of an examination of England’s imperial designs and Oliver Cromwell’s millennial beliefs, in part three. Finally, part four follows the Barbadian slaves, Nell and Yaff, to analyze the role of religious doctrine and conversion, imperial competition, and slavery in the British sugar kingdom. In this “serial microhistory,” the author captures the entangled experiences of people who crossed imperial borderlands, survived slavery, and negotiated their identities in the colonial Caribbean.

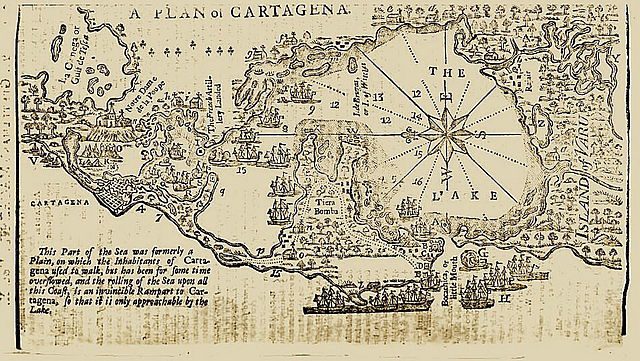

Block uses both local and metropolitan archives to offer vivid and revealing portrayals of people’s lives. Records of the Inquisition and of the Jesuit School in Cartagena of the Indies illuminate how Spanish officials negotiated Isabel Criolla’s legal position after she had run away and denounced her mistress’ physical abuse. Isabel presented herself as a Christian woman before the tribunals, raising critical questions about the boundaries of cruelty among Spanish Christians. For Isabel, religion functioned as a rhetorical instrument of self-suffering and as a strategy to escape humiliation. Religion also empowered Spanish officials to rule in Isabel’s favor, taking her away from her mistress. Sources from the National Archives of Madrid and London provide Block with materials to challenge the dominant narrative of antagonism between Catholic and Protestant imperial powers. She illustrates how Spanish and British merchants worked together to maintain effective trade networks in the Caribbean despite turmoil and allegedly irreconcilable religious differences.

A Linen Market with a Linen-stall and Vegetable Seller in the West Indies by Agostino Brunias, circa 1780.

The complexities Block discovered in the lives of her historical actors demonstrate how European officials also manipulated religious discourses in order to pursue their own lucrative agendas. British commanders who embraced Oliver Cromwell’s millennial promise “to make England a nation flowing with American milk and honey,” also recruited lower-class white seamen and soldiers to work into harsh military discipline in Jamaica. Radical Protestant discourses on Christian martyrdom served Cromwell’s commanders to justify the “enslavement” of Englishmen such as Henry Whistler and to unequally distribute the enemy’s loot. For Block, Cromwell’s “Western Design” concealed tyranny as piety and failed unifying the English nation at home and abroad.

Northern European interlopers, such as Nicolas Burundel, consciously performed the Old World rituals and religious conventions as a tactic for maneuvering the seventeenth-century Catholic orthodoxy. Burundel’s testimony in Cartagena’s Inquisition tribunals elucidates how Europeans embraced different religious discourses as a survival strategy. Burundel performed a Catholic identity while living in Spanish Jamaica and he maintained this position after the Inquisition charged him with the crime of Calvinism. Yet, he shifted his identity to that of “heretic,” hoping for the mercy of the Inquisition officials. For Block, Burundel’s testimony demonstrates that polyglot Northern Europeans became cultural and religious chameleons, who understood that “compliance or duplicity were preferable to conflict or the pain of coercion.”

Christianity also helped slaves maneuver the tensions between Quakers and British officials in Barbados. For Block, Quakerism proved to be a contradictory form of spiritual colonization of the enslaved population. While Quakers aimed to evangelize “faithful” black servants, they also pursued temporal prosperity and complied with the oppressive structure of chattel slavery. The crescent conviction among British that Christians should not be enslaved was influential in two instances. It allowed disenfranchised poor whites such as Henry Whistler to differentiate himself from African slaves, but also excluded the latter and their descendants from spiritual redemptive opportunities. Yet, slaves such as Nell and Yaff understood the inclusive social power of Christianity as a necessary step for obtaining manumission. Ultimately they obtained evangelical instruction, socioeconomic privileges, and freedom by performing loyalty to their masters.

Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean is an excellent book for those interested in the interplay between religion and imperial rivalries. My only criticism is that Block reduces people’s religious experiences to rational instrumentality. She overlooks the Africans and their descendants’ complex spiritual world. One might question if Christianity was merely an instrumental force of social inclusion, a tool to avoid punishment, and a strategy to survive slavery. For instance, many of them were already Christians before arriving to the Caribbean. Perhaps their lived religion was even more entangled than it appears to be for Block.

Mark Sheaves reviews Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution 1750-1816, by Karen Racine (2002)

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott

All images via Wikimedia Commons.