by Justin Heath

“A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners…all howl(ed) in a barbarous tongue…riding down upon (the posse) like a horde from a hell more horrible yet than the brimstone land of Christian reckoning…”: So begins the longest, most vivid sentence in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West.

“A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners…all howl(ed) in a barbarous tongue…riding down upon (the posse) like a horde from a hell more horrible yet than the brimstone land of Christian reckoning…”: So begins the longest, most vivid sentence in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West.

As a young reader of gothic fiction, I always believed that Cormac McCarthy had an unrivaled sense for the macabre. More so than any other contemporary writer, he painted violent and terrible scenes that not only rattled my sense of poetic justice, but also delighted my curiosity about the darker recesses of the imagination. More so than I knew at the time, this mix of impressions also affected McCarthy’s more sophisticated readers. Even as he praised the book as the ultimate realization of the old western as a genre, the literary critic Harold Bloom evidently found it difficult to finish the novel. “The first time I read Blood Meridian,” Bloom confessed, “I was so appalled that while I was held, I gave up after about 60 pages.”

As an aspiring historian, what now catches my attention is not these sensational popular depictions of the Southern Plains tribes, or the “Wild West” in general, but the resonance of these otherwise careworn images in the scholarship of Borderlands Studies. Put simply, most books and articles within this academic sub-discipline still uncritically focus on a narrow range of topics — all replete the familiar scenes of violence, horror, and death.

Juliana Barr’s Peace Came in the Form of a Woman, a study of inter-ethnic diplomacy in the borderlands of Texas, marks an exception to this general trend. In this award-winning book, Barr investigates Hispano-Indian relations in the distinctive setting of the Texas borderlands, where nomadic societies, such as the Comanches and the Apaches, dictated the practices of peace-keeping to their allegedly more powerful Spanish neighbors to the south.

At the northern edge of colonial Mexico in the eighteenth century, a consortium of soldiers, ranchers, and mission Indians were in no position to dictate the terms of peace in the distant lands of “the Far North.” Left without the means to impose their will, the outposts of Texas, such as Bexar de San Antonio, had little choice but to adapt to the local culture of peacekeeping as practiced by their more resourceful indigenous neighbors. This multicultural landscape that Barr illustrates was held together not by signed treaties, maps, or anything of the Spaniards’ diplomatic reckoning, but by the extensions of honorary kinship that transcended “racial” differences between culturally unrelated groups. Within this essentially familial understanding of inter-group networking, Barr argues that it was women – as opposed to men — who served the central role as mediators.

When the Spanish decided to settle the lands of “Los Tejas” in the 1690s, the administrators in Mexico City hoped to install a buffer territory of Catholic missions and Spanish forts along the northern periphery, so as to forestall the advancement of unconquered peoples of “El Norte.” Without any such buffer, continued raids on the more prosperous regions of present-day Mexico threatened to obstruct the extraction of natural resources in one of the world’s first prominent export-oriented economies. Such a view of the geopolitical landscape seems to have guaranteed ineffectual half-measures to contain raiding activities.

A replica of the Mission San Francisco de los Tejas, the first Catholic mission established in East Texas in 1690 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Barr’s study illustrates radical changes in the conduct of borderland diplomacy. In their earliest encounters with nomadic groups like the Caddos, the Spanish often entered into indigenous camps in full regalia, bearing the sacred image of Our Lady of Guadeloupe, who assumed a central place in these processions. Noticing that the Spanish brought no women with them, the Caddos recognized the image not as innately holy figure, but as a proxy for an otherwise absent feminine presence that customarily attended peaceful negotiations between indigenous groups. The men who greeted the Spanish envoys paid homage to the female image by kissing the icon of Santa Maria. The colonists, for their part, interpreted this gesture as auspicious, signaling the Caddos’ eagerness to convert to the Catholic faith. This inference was tragically mistaken, Barr observes, since missionaries would be the choice targets in future raids. Resistance to Catholic missionaries during the first half of the 18th century would also spark decades of violence between the natives of Texas and these recent Spanish arrivals. Although the Spanish always had the ambition to occupy the region, they always lacked the means to locate, much less subjugate, these equestrian peoples.

By the end of the 18th century, after decades of countless defeats, the Spanish townspeople became increasingly sensitive to the significance of women in these diplomatic visits. When the Comanches visited San Antonio in 1772, for instance, the governor of Texas was eager to point out that a woman came at the forefront of the convoy. The implications of such cultural adaptations and what they entailed for colonial-indigenous relations serves as the primary focus of Barr’s inquiry.

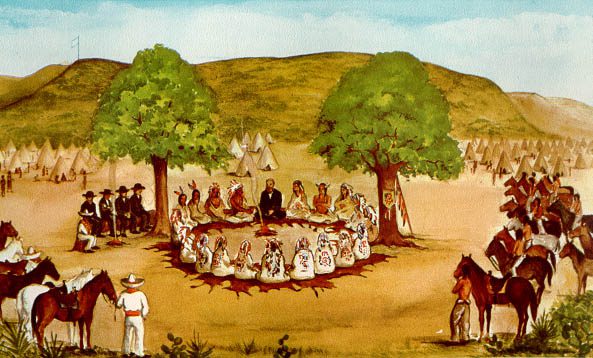

Barr’s study occasions some truly thought-provoking discoveries. By her estimation, peaceful coexistence in Texas had little to do with overcoming perceptions of “racial differences,” since the category of “race” was essentially a European concept that carried little weight in the borderlands. Rather, the complex web of kinship relations focused on the movement of wives, mothers, and daughters – whether voluntary or coerced — to locations that arranged for their safe keeping. As Barr emphasizes, it was the extension of a feminized domestic space across tribal boundaries that brokered trust between men. For this reason, the presidio forts, originally designed to carry out the military occupation of Texas, served as the primary meeting grounds of what Barr terms inter-group “hospitality” networks. In these presidios, the annual distribution of gifts between families and tribal bands cemented peaceful ties between culturally unrelated peoples who often did not speak the same language.

Treaty of Peace by John O. Meusebach showing Colonists with the Comanches in 1847 (via Prints and Photographs Collection, Texas State Library and Archives Commission)

Like most innovative studies, Barr’s impressive work also has its shortcomings. For starters, whenever peaceful relations did break down, Barr is perhaps too eager to blame Spanish diplomatic clumsiness or cultural cynicism. The accuracy of these accusations aside, there is more to the picture than a question of mere prejudicial attitudes. By all accounts, the financial strain of “hospitality” was more considerable than Barr lets on. Many of the Comanches’ demands included items that were not locally produced in Texas. To obtain these gifts in a timely fashion, the treasurers and governors had to maintain a tight logistical operation that connected distant suppliers from Louisiana, Coahuila, and many other places. All of this put a strain on the coffers of the local outpost town, where money was almost always in short supply.

A second problem is Barr’s use of kinship terms. What do words like “brother” mean between former combatants in the 18th-century Southwest? By focusing on the indigenous outlook on peacekeeping, the Spanish experience seems underappreciated, especially when one’s honorary sibling appears more like an extortionist than a guest? On the other hand, by sidelining the idiom of cultural groups, we risk injecting Eurocentric categories into our analysis of events where Europeans were merely one of several groups involved? This problem has a renewed urgency among scholars of Borderlands. With specialists such as Pekka Hämäläinen entertaining notions of a “Comanche Empire,” perhaps it is time that historians turn to the political nuances of South Plains’ speech for much needed clarification.

In spite of these problems, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman is a compelling read. By examining the Spaniards’ adaptation to new cultural surroundings, Barr undercuts the assumption that the peripheries of the Empire were essentially static, underdeveloped communities that awaited their inevitable incorporation into more culturally “advanced” or “rationalized” societies. By focusing on the practice of peacekeeping, Barr shows that Europeans and their descendants held an illusory monopoly over concerns for regional stability, long-distance trade, or extensive social networking. Other groups actively sought to arrange for amicable relations, even if they sought these ends through alternative means.

Also by Justin Heath on Not Even Past:

You may also like:

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra reviews Seeds of Empire by Andrew Torget (2015)

Susan Zakaib reviews Patrons, Partisans, and Palace Intrigues: The Court Society of Colonial Mexico 1702-1710 by Christoph Rosenmüller (2008)

On 15 Minute History: The Pueblo Revolt of 1680