by Edward Shore

On March 5, 2013, Vice President Nicolás Maduro confirmed what many Venezuelans had long anticipated: President Hugo Chávez Frías (r. 1999-2013) had died after an eighteen-month battle with cancer. He was 58 years old. News of Chávez’s death prompted an outpouring of grief among his red-clad supporters in downtown Caracas and a smattering of cheers in the exile communities of Miami. Chávez was an outsized, divisive, and complicated figure who aroused passions on both left and right throughout his fourteen years in power. To his supporters, Chávez was a symbol of Latin American independence and revolution, an heir to Simón Bolívar, and a “champion of the poor” who bucked neoliberalism by redistributing Venezuela’s oil riches to the poor. To his detractors, he was a “strongman” and a “dictator,” an enemy of free enterprise and democracy who consolidated political power in his Bolivarian Revolution and repressed his opposition.

Who was the “real” Hugo Chávez and how will history judge his legacy? Pundits have rehashed and recycled the “hero v. villain” binary in the days after his death, but Hugo Chávez was more complicated than either his allies or his enemies would care to admit. To understand Chávez and his Bolivarian Revolution we need to contextualize the comandante and his movement within the longer history of the Cold War, imperialism and popular mobilization in Venezuela and Latin America more broadly.

President Chávez appearing in Guatemala, 2005 (Image courtesy of Agência Brasil/Wikimedia Commons)

Hugo Chávez Frías was born in the rural state of Barinas in central Venezuela on July 28, 1954. The son of schoolteachers, young Hugo professed a love for history that was matched only by his passion for baseball. At 17 years old, he entered the Venezuelan Academy of Military Sciences in Caracas and became one of the army’s best ballplayers and brightest cadets. However, he soon demonstrated a greater propensity for politics than baseball.

Chávez came of age at the height of the Cold War in Latin America and engaged in the major debates of the era: socialism v. capitalism, electoral democracy v. armed struggle, the United States v. the Soviet Union. In his early twenties, the young army officer criticized U.S. interventionism in Latin America and expressed indignation at the 1973 CIA-backed coup in Chile that toppled Salvador Allende and installed General Augusto Pinochet as dictator. In 1974, Chávez participated in a military exchange program in Peru where het met President-General Juan Velasco Alvarado, a progressive who had seized power in 1968 and initiated a reformist program supported by revolutionaries in the army. Impressed by Velasco’s achievements, Chávez envisioned nationalist, state-led development program in Venezuela steered by a vanguard of progressive military officers. In 1975, Chávez was assigned to counterinsurgency operations in his native Barinas where he encountered a small band of Marxist guerrillas. He developed sympathy for the revolutionaries and grew disillusioned with corruption in the military and Venezuela’s political system. It would not be long before Chávez would express revolutionary ambitions of his own.

Chávez as a young second lieutenant at the Military Academy, Caracas (Image courtesy of Venezuela’s Ministry of Information and Communication)

Throughout the 1980s Venezuela was in chaos. A foreign debt crisis spurred by falling commodity prices pushed the economy into a tailspin. The recession had erased the growth of the so-called “Saudi Venezuela” period of the mid-1970s, when an oil boom had led many Venezuelans to believe they might one day inherit a rich and developed nation. Venezuelan policymakers and technocrats responded by embracing the neoliberal prescriptions of the so-called “Washington Consensus” — devaluing the Venezuelan currency, slashing social programs, and privatizing key industries. However, in the short term these policies only exacerbated poverty and social strife.

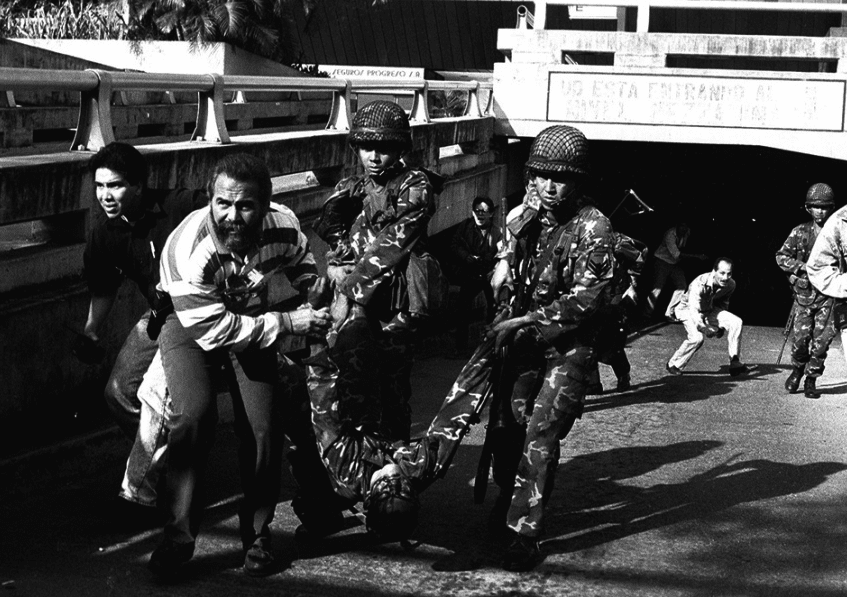

On February 27, 1989, Venezuelans took to the streets of Caracas to protest fare hikes on city buses. The demonstrations quickly devolved into riots and looting as President Carlos Andrés Pérez declared martial law and deployed the National Guard to suppress the revolt. After the dust had settled, more than 500 people had been killed, many of them at the hands of the military, while thousands of businesses were either damaged and destroyed in what later became known as the Caracazo. The Caracazo also had the effect of exposing the incompetence and vulnerability of the country’s civilian leadership. Lt.-Col Hugo Chávez Frías and a clique of leftist officers in the army’s parachute regiment known as the Movimiento Bolivariano 200 began plotting a coup d’état against the Pérez government.

Rebelling Venezuelan civilians and soldiers carry one of their wounded during the failed coup of 1992 (Image courtesy of the Venezuelan National Library)

Chávez led five army units to the Presidential Palace on February 4, 1992, in an attempt to detain the president and arrest the high command of the armed forces. Unbeknownst to the comandante, his plans were betrayed and his rebellion was suppressed by the military. Before his surrender, Chávez asked for and was granted permission to speak on national television. It was a decision the Venezuelan establishment would soon live to regret. Chávez, in full military uniform and donning a red beret, spoke without notes directly to the camera.

“Comrades: unfortunately, for the moment, the objectives that we had set ourselves have not been achieved in the capital. That is to say that those of us here in Caracas have not been able to seize power. Where you are, you have performed well, but now is the time for us to rethink. New possibilities will arise again and the country will be able to move definitively towards a better future.”

Chávez spoke for only a minute, but one phrase managed to capture the imaginations of millions of Venezuelans who had backed the aborted coup: “por ahora” or “for the moment.” The comandante had conceded defeat, but his struggle against the oil oligarchy and their allies in the military had only begun. He spent two years in prison, but his Bolivarian movement had attracted a mass following. Six years later, Chávez was elected president of Venezuela with 56% of the vote.

Chávez addressing the nation over Venezuelan television after the 1992 coup attempt (Image courtesy of Soberania)

What were some of Chávez’s accomplishments? For starters, he managed to reform Venezuela’s ossified and unpopular party system. In April 1999, Chávez called for a national referendum to support his plans to rewrite the Venezuelan Constitution, a proposal that passed with 88% of the vote. The Bolivarian Constitution established a unicameral legislature, mandated protections for indigenous and women’s rights, and expanded access to healthcare, education, food, and housing. Chávez’s supporters claim these reforms have democratized the political process by mobilizing working-class, poor, indigenous, and black Venezuelans who were largely ignored by all previous governments. These were the people who rushed to his defense after a U.S.-backed coup in 2002 removed Chávez from power. His supporters took to the streets in protest and Chávez returned to the presidency two days later.

Second, Chávez pioneered a “Twenty-First Century Socialism” that offered a regional alternative to neoliberalism and market reforms. His administration reversed privatization by nationalizing key sectors of the economy, particularly in the oil industry. His government redistributed petroleum dollars through its ambitious misiones, or social programs that slashed illiteracy in half, reduced extreme poverty by 75%, and expanded free healthcare and education to all Venezuelans. Finally, Chávez’s election triggered the emergence of the so-called “New Left” in Latin America that saw the elections of left-wing presidents in Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil during the 2000s. Chávez was a major supporter of Latin American integration and made the creation of a Bolívar-inspired Gran Colombia the axis of his foreign policy. In 2008, he lobbied for the establishment of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) that merged Mercosur and the Andean Community of Nations . Most recently, the Venezuelan president managed to bring FARC guerrillas and the Colombian government to the negotiating table to discuss an end to that country’s fifty-year-long civil war.

Chávez’s achievements, however, only tell part of the story. While Chávez’s supporters applaud the rebirth of mass politics, his detractors insist that his constitutional reforms have weakened liberal democracy in Venezuela. They criticize Chávez for eroding checks and balances by stripping legislative powers, packing the courts with chavistas, and enhancing the power of the executive branch. They point to Chávez’s declaration of “enabling powers” in 2007 which allowed the president to rule by decree for eighteen months. They also claim that Chávez cemented an insurmountable political advantage by injecting oil revenues into the legislative and mayoral campaigns of his supporters, thereby crowding out the Venezuelan opposition. Human Rights Watch reported in 2008 that Chávez and his administration have engaged in “discrimination on political grounds by eroding the independence of the judiciary and engaging in policies that have undercut journalists’ freedom of expression, workers’ freedom of association, and civil society’s ability to promote human rights in Venezuela.”

Chávez’s critics allege that his misiones reinforced patronage and clientelism. They claim that welfare distribution was contingent upon support for the president’s policies, especially during election years. Meanwhile, a lack of transparency clouded his administration, particularly after he contracted cancer in July 2011. Chávez refused to disclose the severity of his condition throughout his 2012 presidential campaign and the government published scant information on the president’s status following his departure for Cuba in December 2012. Finally, Chávez’s detractors blame his “twenty-first century socialism” for Venezuela’s skyrocketing inflation, free-falling currency, and renewed dependence on imports, especially foodstuffs. Venezuela’s economic woes, alongside soaring rates of violent crime, homicide, and kidnapping in Caracas are part of Chávez’s legacy.

Street mural of Chávez in Caracas (Image courtesy of La Patilla)

What lies ahead for Venezuela and Latin America after Chávez? His handpicked successor, Nicólas Maduro, is likely to defeat opposition candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski, the governor of Miranda, in special elections slated for April 14. Maduro, a former bus union leader, has pledged to expand Chávez’s social programs and has reaffirmed Venezuela’s commitments to its allies, particularly Cuba. However, Maduro lacks charisma and military experience and is unlikely to win over his predecessor’s supporters in the armed forces. Chávez succeeded in broadening the civic responsibilities of the military but he also presided over a fragile coalition of leftist and centrist officers that had grown dissatisfied with Venezuela’s economic performance, soaring crime, and burgeoning narcotrafficking activity along the western border with Colombia. A military coup, carried out by an alliance of military officers and the Venezuelan opposition, remains a possibility, especially given the country’s history of military uprisings.

Finally, the days of leftist populism in Latin America appear numbered, at least for now. Venezuela’s recent economic downturn and the departure of its most charismatic and popular leader threaten statist programs in Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Bolivia. Centrist and center-left coalitions in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia are poised to expand leadership and influence over Latin American affairs. Nevertheless, the specter of Hugo Chávez Frías looms large over Venezuela. Chavista parties promise to dominate the political environment and even centrist leaders like Capriles will be hard pressed to reverse the popular misiones. Future presidential candidates must appeal to Chávez’s broad coalition of poor farmers, slum dwellers, trade unionists, teachers, and workers should they hope to win executive office.

Chávez will be remembered as one of the most influential Latin American leaders of the last one hundred years, entering the ranks of Castro, Perón, Vargas, Pinochet, Cárdenas, and Lula da Silva. The comandante is gone, but the fierce blend of nationalism, populism, and anti-U.S. sentiment he refashioned and recycled will find new voices in Latin America. Adiós and so long, Hugo Chávez Frías…por ahora.

You may also like:

Edward Shore’s review of The Cuban Connection and his review of Che: A Revolutionary Life