NEP’S Archive Chronicles explores the role archives play in historical research, offering insight into the process of conducting archival work and research. Each installment will offer a unique perspective on the treasures and challenges researchers encounter in archives around the world. NEP’s Archive Chronicles is intended to be both a practical guide and a space for reflection, showcasing contributors’ experiences with archival research. This installment explores the complexities of finding the voices of the Yaqui people in the archives of Sonora.

Nota: Haz click aquí para acceder a la versión en español.

Note: Click here to access Spanish version.

In my scholarly quest to understand the history of Indigenous peoples, I have confronted persistent challenges in accessing sources that authentically reflect their experiences and perspectives. These sources are often rare, obscure, and challenging to interpret. The historical records written and left by the Indigenous populations in northwestern Mexico are scant, particularly those predating the twentieth-century. Most Indigenous individuals were not literate, lacked knowledge of the colonizers’ language, and had limited means to document their thoughts and feelings. As a result, our understanding of Indigenous history relies heavily on accounts written by outsiders such as missionaries, explorers, political figures, and military personnel. While we may occasionally stumble upon valuable firsthand documents, such as letters from literate individuals, these discoveries are exceptionally rare.

I have been particularly interested in the history of the Yoemem or Yaquis. They are one of the largest Indigenous groups in what is now known as the state of Sonora, in northwest Mexico. Over the past centuries, they have had to confront different governments that have tried to dispossess them of their lands, autonomy, and identity. Despite constant efforts to subdue them and even exterminate them, they persist and resist to this day.

To address the challenge of finding their voices in the primary documents, recently I have turned to judicial archives as a valuable alternative source for accessing Indigenous testimonies. Hermosillo, the capital city of Sonora in northwest Mexico, is home to two public archives that house juridical documents: the General Archive of the Judicial Branch of the State of Sonora (Archivo General del Poder Judicial del Estado de Sonora) and the Archive of the House of Legal Culture of the Supreme Court of Justice (Archivo de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica). Both archives divide their collections into two categories: the historical, which contains documents created prior to 1950, and the concentration collection, which includes documents produced after 1950.[1] The archives were created in the nineteenth-century and are maintained and funded today through funds allocated by the state government, and the federal government, respectively.

Over the past few years, I have extensively researched both historical archives in pursuit of the voices of the Yaqui people, especially from the Yaqui War period. This violent era started in 1824 under the leadership of Juan Banderas, a Yaqui chief who upraised against the Mexican government to defend their autonomy. The conflict only worsened after the Liberal projects that sought to privatize indigenous communal lands and, especially, during the Porfiriato period, when it turned into an extermination war. Although they barely survived those years, the Yaquis continued revolting against the government until the 1930s when they finally surrendered after being ferociously attacked by the revolutionary authorities.

While the content of both repositories shares similarities, there are also notable differences arising from different duties and objectives, both historical and current day. These variances manifest not only in their content but also in the preservation, cataloging, and accessibility of the historical documents. In this article, I introduce the history of these archives, the experience of researching there, and what we can discover.

Before I do that, let me briefly explain how the judicial system works in Mexico and how a case’s file might end up in one archive or the other, Since the 1824 Constitution and the creation of Penal Codes,[2] crimes in Mexico have been classified as common law (fuero común) or federal law (fuero federal). Common law cases are processed in state courts, while federal law crimes go to district courts (juzgados de distrito). If an accused individual (of either common or federal law crimes) feels they were unfairly sentenced, they have two options at their disposal. First, they can file an appeal for a second instance review. If this is unsuccessful, they can seek recourse through the “amparo” or legal protection process, which is carried out in collegiate courts or, if necessary, in the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación).[3]

Common law crimes are those that directly affect individuals, such as cattle rustling, rape, robbery, or inflicting injuries. The files of those crimes (and of their appeals, if promoted) can be found at the General Archive of the Judicial Branch of the State of Sonora (AGPJ). Federal law crimes, on the other hand, defined as those “that affect the well-being, economy, heritage, and security of the nation”, such as sedition, smuggling, or immigration violations.[4] Documentation related to federal law crimes, as well as any amparo processes, canbe found at the Archive of the House of Legal Culture of the Supreme Court of Justice (ACCJ).

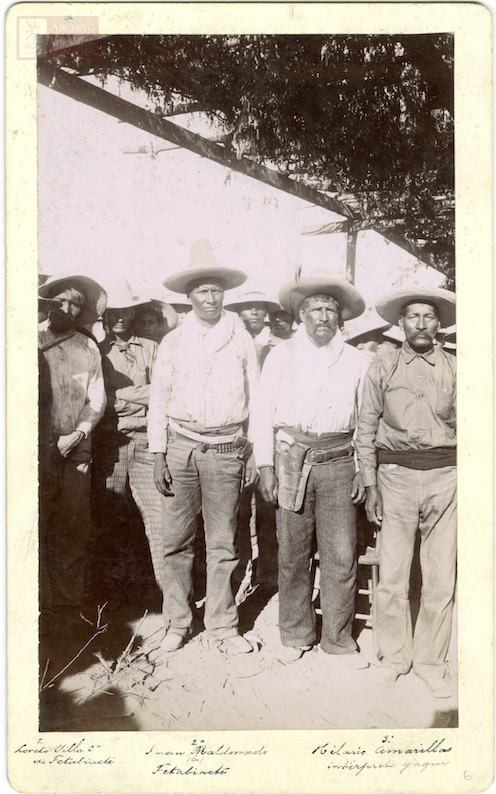

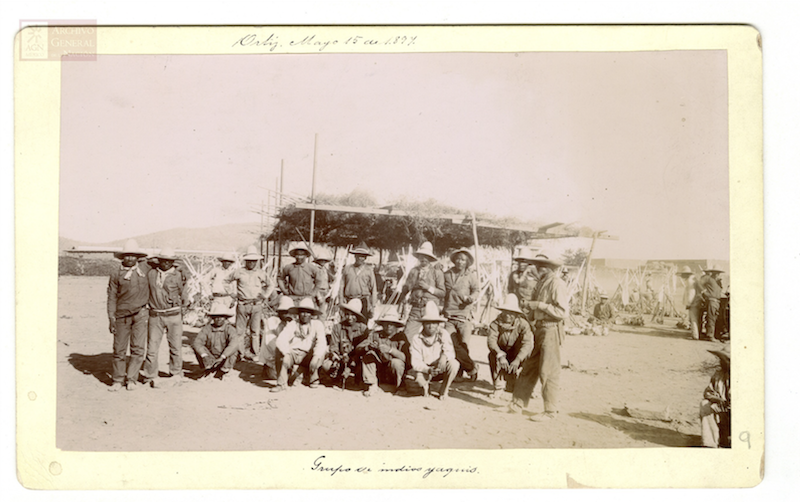

Pictures taken by author.

The state’s judicial archive

The AGPJ, like all archives, has its own history. Since 1833, when the Mexican State of Occidente (Estado de Occidente) split into Sonora and Sinaloa and the first local Constitution was established in the state, decree number 13 ensured the permanence of the Supreme Powers, including the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, in Hermosillo, along with their respective archives. Over a century later, in 1957, a new decree established a dedicated archive under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice to organize and safeguard documentation exclusive to the Judicial Branch of the state. The most recent law affecting this archive, dated 1996, designated the AGPJ as an auxiliary body of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, aiming to professionalize and streamline the judicial branch’s operations.[5] However, because of its new nature and likely limited resources, efforts to identify, catalog, and organize the documentation have not been completed.

For many years, the documentation of this archive was kept in the General Archive of the State of Sonora (AGHES), on Garmendia Street in the Historic Center of Hermosillo. However, since 2000, the archive relocated to a new building right next to the Hermosillo Prison, on Blvd. de los Ganaderos. The interior of the archive is everything you would expect from a bureaucratic building, and even worse, a judicial one. The lack of windows, the small space, and the minimalist and utilitarian decoration of the consultation room invite you to put yourself in the shoes of the imprisoned individuals whose files you find in front of you. Fortunately, you can find brightness and warmth in the archivists and employees of the AGPJ.

To consult this archive, it is essential to establish good relations with the archivists since consulting the documentation presents a unique challenge as there is no catalog or reference guide. So, you either already know the references to the files you want to consult because you saw them cited in someone else’s work (and sometimes even then, they have been changed), or it is your lucky day and what you are looking for has already been identified by the archivists. This said, I must recognize recent efforts by Sonora’s Judiciary Branch to hire historians and archivists to work on the preservation and cataloging of the 3036 files (legajos).

I actually knew (or thought I knew) the references to the files I wanted to consult because a friend of mine had been to the archive before and directed me to a very interesting case. After filling out a form specifying the reference, the archivists asked me for a photo ID and went to get the files for me. They asked me to wear latex gloves, a face mask, and to handle the documents carefully. Unfortunately, after hours of turning one page after another, I was not able to locate case I was looking for. But as is always the case with archival work, I found many other interesting and pertaining documents.

Sonora’s federal judicial archive

Visiting the House of Legal Culture of the Supreme Court of Justice is a different experience. The archive is housed in a building constructed in 1945 (it was a literal house before), located in the Razo neighborhood in Hermosillo, across from the iconic Madero Park. In 1998, the Supreme Court acquired the property to establish the House of Legal Culture in Hermosillo which is much more than just an archive. Named after “Minister José María Ortiz Tirado,” this House is one of 36 across the country that serves as a public venue “to promote legal culture, facilitate access to justice, and reinforce the Rule of Law (Estado de Derecho).”[6]

Visitors are required to sign a letter pledging responsible use of the documentary materials and a commitment to share any publications with the Archive. To request specific files, visitors must provide details such as the collection (“Amparo” or “Penal”), the year, file number, and the names of the processed individuals. But –strikingly—they ask for all of these reference details when they do not have a catalog of their own.

For the Amparo collection, I had to visit the library at the University of Sonora to check out their catalogs for the archive. They were produced by Hans Ildefonso Leyva Meneses (covering 1900-1917) and Mayel Barboza Enciso Ulloa (1918-1928) as part of their bachelor’s degree requirements.[7] Fortunately, a complete digital catalog for the Penal collection, although authored anonymously, has been in circulation among local historians for years now (shout out to the unknown author!).

The consultation room is nothing like the aforementioned archive. It is well-equipped, spacious, and comfortable, and offers the researchers a view of the garden trees and cacti, as well as a beautiful feline family (federal institutions tend to have bigger budgets). Here, too, you are required to wear latex gloves and a face mask. And, unfortunately, due to identity protection measures (the dead have a right to privacy too), photographing the documents is not allowed in this archive. As a result, thorough consultation can be time-consuming, but worth it.

The documents and the “voices” we can find.

Due to the similar nature of the documents found in these two archives, they exhibit clear similarities in format, sequence, purpose, and content. The length of the file will depend on the severity of the crime, the number of individuals involved, the complexity of the investigation, and the volume of evidence. The vocabulary and structure of the documents are rigid, and formal, and showcase the positivist ideology of the time.

The structure of the document typically consists of three main parts: a description of the crime and those involved; testimonies and evidence; and the sentence or verdict.[1] Although analyzing the whole case can shed light on the nuances of the judicial system, I am usually drawn to the depositions and accounts, because it is here where you begin to find the voices of the indigenous peoples. Moreover, the bureaucracy of judicial cases presents us with the biographical information of those involved such as name, age, marital status, occupation, and place of birth and residence, followed by physical descriptions of the accused. The document also indicates if any of the persons involved were indigenous (indígena). However, specifics about their ethnic group are rare

To determine if the individual in question was Yaqui, key indicators include their name and surname—such as Bacasegua, Buitimea, or Matus, which are traditionally Yaqui. Additionally, the location of events, particularly in or near Yaqui territories like Vicam, Torim, or Guaymas, can provide further confirmation. While this method is effective, it is important to note some potential pitfalls. Firstly, it’s easy to mistakenly confuse Yaquis and Mayos (also native to Sonora and Sinaloa) due to their cultural and linguistic similarities. Additionally, throughout time, Yaquis have exhibited significant mobility throughout the whole state and even beyond political borders, so it was not rare to find them in Álamos or in Cananea.

Although these sources are revealing, the voices and worldviews of the Yaquis are not intact in the archive. And it is crucial to understand how their testimonies were collected in any given case. Usually, in regular proceedings, they responded to specific questions rather than were allowed to speak spontaneously and freely. If, on the other hand, the individual or individuals were looking to get legal protection (amparo), they presented their testimony in written form before the Supreme Court.

It is also important to emphasize that statements in civil or criminal procedure documents are not verbatim transcriptions. Instead, they are presented by the scribes in an abridged and polished (again, very positivist) format through indirect narration. In this sense, we might think that the legal protection cases present a less manipulated testimony since they could write them themselves. However, considering the historical context and supported by the amparo cases that I have consulted, the Yaquis who sought legal protection were rarely literate. In many instances, other interested parties assisted in the case, often with personal interests at stake. In addition to oral and written testimonies, one can sporadically find other types of evidence, such as letters, receipts, contracts, and even material records.

So, if we are presented with a filtered and mediated testimony of the indigenous peoples, how can we find their voices and worldviews? Having a deep understanding of the historical context and the way the judicial process took place provides the best starting point. Carefully analyzing the declarations and contrasting and comparing them with other sources (both primary and secondary) allows us to identify potential biases, misunderstandings, distortions, or erasures. Interpreting the sources with an Indigenous framework can also help us gain insights into the meaning, vocabulary, nuances, implications, and even silences of the testimonies. With a thorough analysis, judicial documents can give us a glimpse, and sometimes even more, to Yaquis’ perspectives, values, and worldviews.

These archives are a window to observe how the Yaquis navigated and interacted with the Mexican legal system at a time when the government persecuted and aimed to exterminate them, and how they were represented or misrepresented in judicial processes. Judicial documents showcase how the Yaquis were being targeted not only by the government, but the Sonoran population as well, and how the Yaquis were also the perpetrators of common and federal law cases during the time of war. They provide details and testimonies on revolts, “seditious activities”, and overall disobedience to the government, and they also give us a glimpse into their quotidian lives and how they resisted the war.

The collections of the Archive of the Judicial Branch of the state of Sonora, and the Archive of the House of Legal Culture offer valuable insights into the history of the Yaqui people in the 19th and early 20th centuries. I hope my approach and methodology can be a model for those interested in delving into legal documents in other parts of Mexico, as each federal entity has its own branches of these archives. Despite the challenges each of them presents, these archives are a rich and often underutilized source of information for historians researching not only legal matters but also the broader history of Sonora and its Indigenous and non-indigenous populations.

I would like to express special thanks to all the archivists at the Archives of the Judicial Branch of the State of Sonora, in particular to Bennya Román Flores, whose generosity and dedication have been fundamental for the completion of this work. I also thank the collaborators of the Casa de la Cultura Jurídica in Hermosillo, especially Adrián Pérez, for his patience and constant support while consulting multiple boxes of documents.

Raquel Torua Padilla is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She holds a B.A. in History from the Universidad de Sonora and is currently a CONTEX Fellow. Her research focuses on the history of Indigenous peoples in the Northwest of Mexico and the U.S. Southwest, with a particular emphasis on the Yaqui people. Her current projects examine Yaqui militias and their diaspora during the 19th and 20th centuries.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

[1] The procedures for consulting the Concentration archives are different from those of the historical part of the archive. In this piece, I will only discuss the historical collections of both archives.

[2] Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, penal codes for each state continued to be created and adapted.

[3] García Ramírez, Sergio. 1998. Panorama del derecho penal mexicano. Derecho penal. Mexico: UNAM, McGraw-Hill.

[4] Pérez Moreno Colmenero, Silvia. 2001. Valores para la democracia. Delitos e infracciones administrativas. México: Instituto Nacional para la Educación de los Adultos. 09/13/2024 http://www.oas.org/udse/cd_educacion/cd/Materiales_conevyt/VPLD/delitos.PDF

[5] “Archivo General del Poder Judicial del Estado”. 09/13/2024: https://www.stjsonora.gob.mx/ArchivoPJE/#:~:text=Dentro%20de%20nuestros%20archivos%20se,Estado%20de%20Sonora%20y%20Sinaloa.

[6] “Casa de la Cultura Jurídica en Hermosillo. Ministro José María Ortiz Tirado”. 09/13/2024: https://www.sitios.scjn.gob.mx/casascultura/casas-cultura-juridica/hermosillo-sonora

[7] Leyva Meneses, Hans Ildefonso. 2004. Catálogo para las fuentes documentales de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica en el estado de Sonora, serie juicios de amparo, 1900-1917. Tesis de licenciatura. Hermosillo: Universidad de Sonora. And Barboza Enciso, Ulloa. 2004. Catálogo del archive de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica en el Estado de Sonora del Poder Judicial de la Federación, sección juzgado quinto de distrito del quinto circuito, serie juicios de amparo, 1918-1928. Tesis de licenciatura. Hermosillo: Universidad de Sonora

[8] Presented either by writing, in legal seeking cases, or by interrogation, in civil and criminal proceedings.

[9] In this case, information on whether the informant speaks Spanish or not, and whether an interpreter was used, is also available.