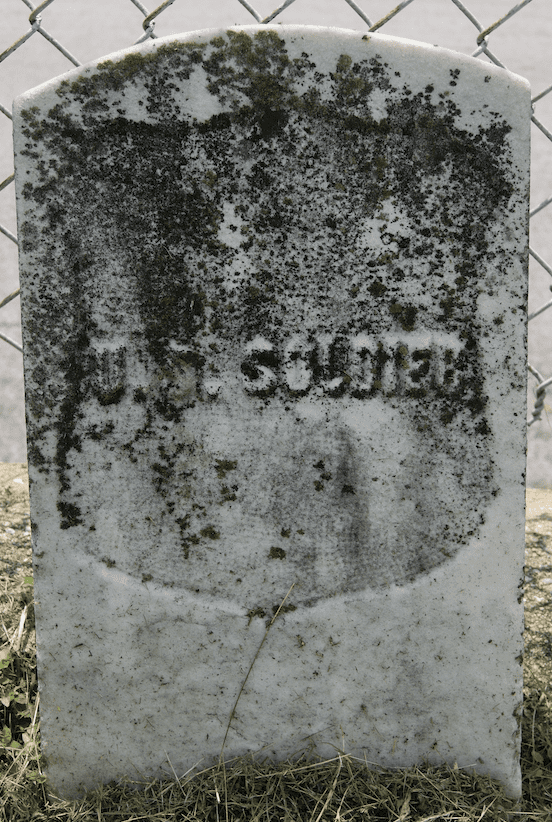

Seven marble head stones lie along a chain link fence in the Old Grounds of Austin’s historic Oakwood Cemetery. Their inscriptions read simply “U.S. Soldier.” These graves are Austin’s own unknown soldiers, men whose identities were lost over time and whose existence is mostly forgotten in the bustling twenty-first century Texas capital. They are also some of the last tangible remnants of the United States Army’s occupation of Austin during the Reconstruction years, a period that is often overshadowed by the deadly four year struggle between North and South that preceded it.

The recent sesquicentennial of the American Civil War occasioned an outpouring of scholarly commentary, public programming, and commemoration. No such effort will be made to recall the drama of Reconstruction, an effort that began while the Confederacy still clung to life and ended in the aftermath of the 1876 presidential election. Historians today see the Civil War and Reconstruction not as discrete events, but as a critical period in a wider nineteenth-century struggle over issues of race, citizenship, individual rights, and the relationship between the state and federal governments and individual Americans.

Scholars debate exactly how much Reconstruction accomplished and whether more radical policies were either desirable or possible, but the long-term impact of Reconstruction legislation, especially the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution, is undeniable. On the ground level, the United States Army played a key role in supporting the operations of the Freedmen’s Bureau and in protecting white unionists and the formerly enslaved from the wrath of defeated Confederates. The seven men who lie in Oakwood Cemetery today took part in the struggle of Reconstruction in Texas, a struggle that in many ways was simply a continuation of the American Civil War.

Emancipation and Reconstruction arrived in Texas on June 19, 1865 in the form of the Union Army. Within weeks, Union forces entered the state from several directions and proceeded to station troops in the most heavily populated areas. Austin was occupied on July 26, making it the last Confederate state capitol to fall to Union forces. Volunteer units, who made up the vast majority of the Union Army during the war, were the first to garrison Austin. The Second Wisconsin, First Iowa, and Seventh Indiana Cavalry regiments, under the command of General George A. Custer, camped on the northern outskirts of town in the fall of 1865.[1] As early as November 1865 the volunteer forces were being mustered out of the service and in 1866 they were replaced by Regular Army units. Although troops began to be sent to Texas’ western frontier in the fall of 1866, others remained in Austin and other portions of the eastern half of the state to maintain order and combat rampant violence aimed at suppressing the interracial political coalition represented by the fledgling Texas Republican party. The United States Army maintained at least a small garrison in Austin until 1875.[2]

A recently published work on Oakwood Cemetery says that the men who are buried there today were victims of a cholera outbreak that took place among Custer’s troops, who were encamped along Shoal Creek. If they were members of Custer’s cavalry, they were veterans of the Civil War as well as participants in the Reconstruction occupation of Texas. Although newspaper reports from the time do not mention a cholera outbreak, the unit histories of the regiments stationed in Austin reveal that nearly 86 percent of the casualties they sustained during their service were from disease. Along with other casualties, the men are believed to have been buried on the grounds of the historic Neill-Cochran house, which was used as a hospital by the Army from the fall of 1865 until March 1867.[3] In the 1890s most of the bodies along Shoal Creek were supposedly exhumed and reinterred elsewhere, but the seven men were forgotten until a flood exposed their graves some time prior to 1911, at which point they were transferred to Oakwood Cemetery.[4]

As Drew Gilpin Faust illustrates in This Republic of Suffering, the federal government faced a monumental task in attempting to locate and identify the Union dead in the years following the Civil War. Between 1865 and 1871 303,536 Union dead were relocated to national cemeteries, at a cost of over $4 million. Only 54 percent of the bodies were identified. One of the major obstacles confronting efforts to identify and move the Union dead to national cemeteries was the intransigence of former Confederates, who did not hesitate to remove headboards and otherwise desecrate Union graves. In contrast, African Americans in the South proved to be the best allies of federal investigators who labored to document and care for Union graves.[5] In fact, David W. Blight argues that the first Memorial Day commemoration took place in Charleston, South Carolina in 1865, when formerly enslaved Charlestonians held a memorial service for Union prisoners of war who had died while in captivity at a local race track.[6] The culture of commemoration established by Americans during the Reconstruction years continues in the modern Memorial Day holiday.

Were Austin’s unknown soldiers forgotten due to malice toward occupying US troops? On the one hand, Travis County had voted against secession in the 1861 referendum and many prominent unionists resided in Austin. Custer’s troops camped on land owned by Elisha M. Pease, a pre-war governor and moderate unionist who would serve again as governor under the military government established by the Reconstruction Acts in 1867. The owners of the Neill-Cochran home, S.M. Swenson and John Milton Swisher, were both unionists as well, although Swisher worked for the state of Texas during the war.[7] According to the records of the Texas State Cemetery, part of the cemetery was set aside during Reconstruction for burials of Army personnel, a move that hardly seems to indicate hostility toward the occupying soldiers. Sixty-two Reconstruction-era soldiers were eventually transferred from Austin to the San Antonio National Cemetery in the late nineteenth century.[8] The men buried in Oakwood may have simply been the victims of negligence or error.

On the other hand, although relations between Austinites and the occupying federal soldiers appear to have been generally peaceful, Amelia Barr recorded that the town was “practically in mourning” in the aftermath of Confederate defeat.[9] Libby Custer, who accompanied her husband to Austin, recalled that “it was hard for the citizens who had remained at home to realize that the war was over, and some were unwilling to believe there had ever been an emancipation proclamation. In the northern part of the State they were still buying and selling slaves.”[10] Most white Texans steadfastly opposed the Reconstruction program of advancing racial equality, often violently. In later years “Lost Cause” propaganda and the Dunning school of Reconstruction history would paint the Reconstruction period as a time of corruption, misrule, and tyranny. Ironically, a town that was known for its large unionist population during the secession crisis became dotted with Confederate memorials during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The physical space of Oakwood Cemetery illustrates the workings of Texas historical memory over time. Approximately twenty yards directly north of the unknown soldiers is a large obelisk dedicated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1909 to General Tom Green, an officer in the Republic of Texas army and a Confederate general who was killed in action in 1864. Monuments to other individuals are scattered throughout the cemetery, some with Texas Historical Commission markers that tell their stories. In their midst, these seven marble headstones lie adjacent to Navasota Street, unknown and largely forgotten, with nothing to explain their significance to visitors. Although controversies over Confederate statuary and school names draw the most media attention in twenty-first century Austin, the long shadow of the Civil War and Reconstruction lingers in the city’s oldest cemetery, at once hidden and in plain sight.

Notes:

[1] Austin Southern Intelligencer, October 26, 1865 and November 9, 1865.

[2] Thomas T. Smith, The Old Army in Texas: A Research Guide to the U.S. Army in Nineteenth-Century Texas (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2000), 54, 104-114.

[3] Kenneth Hafertepe, Abner Cook: Master Builder on the Texas Frontier (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1992), 148.

[4] Save Austin Cemeteries, Austin’s Historic Oakwood Cemetery: Under the Shadow of the Texas Capitol (Austin: Save Austin Cemeteries, 2014), 73; email correspondence with Dale Flatt and Kay Boyd, May 23, 2016; Lorraine Barnes, “Only Stones Remain of US Soldiers,” The Austin Statesman, September 28, 1955; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_Regiment_Iowa_Volunteer_Cavalry; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2nd_Regiment_Wisconsin_Volunteer_Cavalry; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/7th_Regiment_Indiana_Cavalry.

[5] Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 211-238.

[6] David W. Blight, “Forgetting Why We Remember,” May 29, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/30/opinion/30blight.html?version=meter+at+1&module=meter-Links&pgtype=article&contentId=&mediaId=&referrer=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.davidwblight.com%2Fpublic-history%2F2015%2F5%2F26%2Frestoring-memoriam-to-memorial-day&priority=true&action=click&contentCollection=meter-links-click

[7] http://www.nchmuseum.org/about/; https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fsw20; https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fsw14; https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fpe08.

[8] Email from Jason Walker, May 25, 2016.

[9] Quote in David C. Humphrey, “A ‘Very Muddy and Conflicting’ View: The Civil War as Seen from Austin, Texas,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly (Jan. 1991): 412.

[10] Elizabeth B. Custer, Tenting on the Plains, Or, General Custer in Kansas and Texas (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), 138.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.