The 1960s saw an explosion of student activism across the globe. This increase in youth movements for social change was so influential that U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson had the Central Intelligence Agency illegally monitor student movements both at home and abroad. After some investigation, the CIA produced an over two-hundred-page report, titled “Restless Youth,” which discusses their findings on the activities of students and student groups in the United States as well as nineteen other countries across Asia, Africa, Latin America, Western and Eastern Europe.

The report broadly details the general trends of how the “restless youth,” particularly university students, engaged in a range of anti-establishment activism such as university occupations, street marches, and sit-ins. The CIA report analyzes what issues caught the attention of students, whether they organized ad hoc or within existing organizations, how many students were attending universities, how they connected with other social groups, how they transnationally exchanged ideas, and what ideas inspired them to action. Overall, the report argues that many of the students turned to activism because of their frustration with the socioeconomic and political status quo and that they demanded more from their universities, communities, and governments.

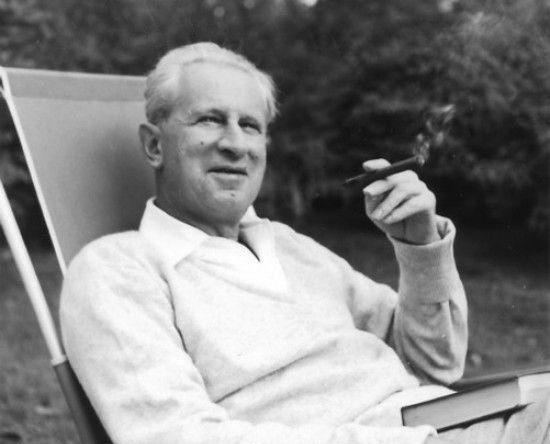

The CIA report also notes that many students, mostly American and European, were inspired to protest by “Marxist social criticism” and the writings of C. Wright Mills, Frantz Fanon, and especially the American critical theorist and sociologist Herbert Marcuse. This Marxist social criticism, also known as Marxist or socialist humanism, stresses the importance of Karl Marx’s early writings and the need for a critical praxis directed against capitalism as well as against traditional Soviet or statist Marxism. Herbert Marcuse was a proponent of socialist humanism and significantly collaborated with the most well-known Marxist humanist philosophical movement of the time – Yugoslavia’s Praxis School.

The members of Yugoslavia’s Praxis School were prominent professors in the Faculties of Philosophy at both the Zagreb and Belgrade universities who supported Yugoslavia’s protesting university students in 1968. The CIA report has an entire chapter dedicated to the student movement in Yugoslavia, yet, this eleven-page section oddly makes no mention of the Praxis School and the support its members gave to Yugoslavia’s protesting university students. The report clearly makes the connection between Herbert Marcuse, Marxist humanism, and student protests, but it fails to make the broader connection to the socialist humanist Praxis School of Yugoslavia and its affiliates who joined university students in protest in the summer of 1968.

How could the CIA have missed this? Although the authors considered student activism to be a growing threat and a “worldwide phenomenon” fueled in part by this particular philosophical discourse of socialist humanism, they didn’t seem to be interested in the leading socialist humanist movement of the time, despite its influence on students in Yugoslavia and beyond. The Yugoslav government, on the other hand, didn’t miss this connection and became extremely interested in the Praxis School. Although the movement wasn’t pro-capitalist or anti-socialist, the Yugoslav leadership still viewed it as a threat due to its criticism of the ruling party – the League of Communists of Yugoslavia – for not fulfilling its promises to create a more just socialist society. Similar views toward student protests were taken by the authorities in nearby countries: in Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring and in Poland. The Czechoslovak government also monitored its growing student movement and produced its own report which noted the students’ criticism of Czechoslovak socialism.

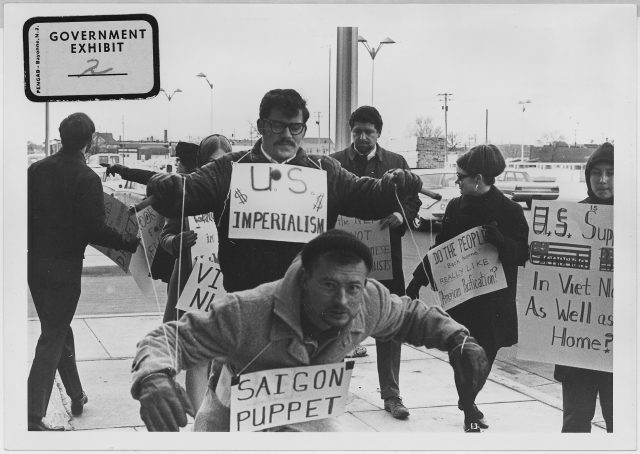

The student occupation of the University of Belgrade (via The Modern Historian).

Following the student occupation at Belgrade University in June 1968, the Yugoslav authorities quietly cracked down on dissenting students and professors. The main target was the leading cohort of the Praxis School, professors in the Faculty of Philosophy at Belgrade University. Slowly, but surely, eight professors from Belgrade – Mihailo Markovic, Ljubomir Tadic, Miladin Zivotic, Zagorka Golubovic, Dragoljub Micunovic, Nebojsa Popov, Triva Indjic, and Svetozar Stojanovic – were removed from their professorships at the university. The Yugoslav authorities claimed that the professors were the “ideological inspiration” and “practical organizers” of the student demonstrations and university occupation and as such needed to be stopped at all costs. They had become too influential and were improperly educating students with ideas that the Yugoslav socialist system of “self-management” was flawed. Aside from being sacked from their university positions the professors also lost financial support for their research and funding for their publication, the Praxis journal, was essentially cut. Although the Belgrade professors didn’t organize the protests, their Marxist humanism consciously or unconsciously provided the intellectual platform for students to criticize the Yugoslav system. The CIA was never able to put these pieces of the puzzle together and failed to capture this source of student discontent both at home and abroad.

Additional Sources:

Mihailo Marković and R. S. Cohen, Yugoslavia: The Rise and Fall of Socialist Humanism: A History of the Praxis Group. (2005)Paulina Bren, “1968 East and West: Visions of Political Change and Student Protest from across the Iron Curtain,” in Transnational moments of change: Europe 1945, 1968, 1989, P. Kenney and G. Horn, eds. (2004)

Andrew Weiss reviews a book about student protests in 1968 Mexico: Plaza of Sacrifices: Gender, Power, and Terror in 1968 Mexico by Elaine Carey (2005) .

Nancy Bui discusses the 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War from a Vietnamese American Perspective.

Mark Lawrence looks at an earlier CIA Study: “Consequences to the US of Communist Domination of Mainland Southeast Asia,” from October 13, 1950.

![]()