The most terrible things are quickly learned,

And beauty will cost us our lives.

-Silvio Rodríguez

A romero is a pilgrim, comrade. I guess we are all pilgrims, to some degree, though some pilgrimages seem to go on forever, while others end abruptly.

When Pope John Paul II came to Chile in April of ’87, the local church tried to script his visit. They wrote him a theme song and they played it non-stop the whole week: Messenger of life, pilgrim of peace. But John Paul was no friend of solidarity, human rights or poor people who got organized. That was all communism to him. Polish Jesus hated communists. The Holy Father’s Messiah became flesh and dwelt among us to impose order on a chaotic world with neoliberal capitalism, an M-16 and logistical support from the CIA.

Ex officio, the Pope aligned himself with authoritarian figures, especially if they seemed anti-communist. That didn’t square with the worldly politics of the Second Vatican Council, and he knew it. He had done everything in his power to roll back the Council, to mystify the crowds with papal pageantry and impose his moral authority using a constant, authoritative threat of hell. The way it used to be, in the good old days.

Communism was John Paul’s childhood trauma. He knew what it was like to be under the Soviet thumb. Behind the Iron Curtain, it was illegal to be Catholic, and it was illegal to have lots of money. So, when John Paul was all grown up and flying around the planet in his handsome white gown, he was most comfortable with anti-communist Catholics who had lots of money. Of course, in Latin America, those were the right-wing oligarchs; and dictators, torturers and death squads who supported them. I can’t imagine he was ignorant of their methods. I guess he figured it was for a good cause.

John Paul’s visit to Chile in ’87 was supposed to be a celebration. Everyone knew that he was conservative. Popes are supposed to be conservative. But the team that prepared the visit was the old guard, Cardinal Silva’s boys, the guys who had created la Vicaría, the soup kitchens, and the basic communities. All the things John Paul found suspicious.

That was behind the scenes, though. In ’87, the show needed a happy ending. Javier Luis Egaña was the producer. He always got the impossible jobs. His team prepared the speeches, the songs and the program. They made it ambiguous enough for Vatican approval, but edgy enough so that it wasn’t a lie. That was as good as it got.

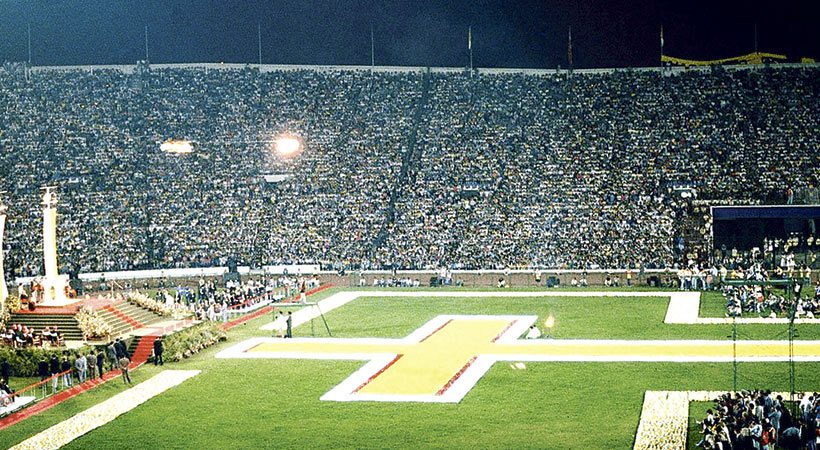

A Pontifical visit to the National Stadium was controversial enough. The Stadium had been used as a gigantic cattle pen for suspected communists after the coup. People were tortured there, and some were shot. The script included a sprinkling of holy water. That could be read as the re-consecration of a desecrated place. It could also be understood as a Papal blessing for the bloodiest atrocities of the military coup.

By ’87, the coup seemed like ancient history to the younger crowd. The Stadium rally was just another big event, for them. You had to have tickets, to get in. They were free, but there were quotas for parishes, movements and Catholic schools. The team had printed seventy thousand tickets, which was the capacity of the stadium, including standing room. But there were ninety thousand tickets, comrade.

The JJCC had gotten hold of one and printed up twenty thousand copies for their all their militants. The kids from la Jota were told to go early. They knew that, at some point, Carabineros would have to shut the gates. We went early, too. We were packed in like sardines, a crowd calamity waiting to happen. Over the loudspeakers, we were asked to kindly stand sideways so more people would fit. When the gates were sealed, ten thousand devoutly Catholic kids with real tickets were left outside. They were pretty pissed. And a quarter of those who were already inside didn’t even know the Our Father.

Communist Youth from the JJCC looked like normal kids from poor parishes. Once inside, the red flags and banners unfurled. The hammer-and-sickle was as omnipresent as the crucifix and the Virgin Mary. They kept it light, but their slogans didn’t exactly come from the New Testament. La Jota went to the Stadium to get noticed, and the Holy Father was not amused.

That wasn’t all. The Pope walked right into a trap so ingenious that James Bond couldn’t have set it up. It must have been the Holy Spirit, comrade.

We had been there since the middle of the afternoon. The sun was hot. We were hungry. Everyone was already a little punchy. The Pope arrived about eight. It was getting dark, so, in his whites, John Paul became this bright light shining in the darkness.

His command of Spanish was not great, but his pronunciation was elegant. The speeches had been carefully prepared, and he had a theatrical flair. Reaching for climax, he asked the badly overheated crowd, Do you renounce the idolatry of power?

Everyone answered, ¡Sí!

He continued, Do you renounce the idolatry of money?

Again, everyone shouted, ¡Sí!

Three is golden, and he went for it. Do you renounce the idolatry of SEX?

There was a brief and deafening unanimous silence. Then, altogether, a loud, resounding, ¡Nooo! The Holy Father was noticeably disturbed. He repeated his question with gravity, and he managed to get a lukewarm, Well, yeah, I guess… from the Legionnaires of Christ and the Opus Dei, in their coats and ties, sitting in the box seats.

Of the 80 thousand people present, 90 percent thought the whole thing was terribly funny. The Holy Father had to lighten up. The authorities blamed the JJCC, but that was ridiculous. The response had been massive, universal and spontaneous.

The speechwriters had committed a strategic error. They had failed to allow for the comic wit of Chilean youth. That was picardía, comrade, an acute awareness of the ridiculous, more Chilean than empanadas and red wine. Picardía was necessary for survival, and indulgently tolerated by the older generation. They might scold and laugh at the same time, happy to be reminded that they had all been young once.

But His Holiness wasn’t Chilean, he didn’t get the joke and he was sanctimoniously furious. He had chosen the topic. His Most Reverend Excellency had a personal vendetta against youthful genitalia. That was the one line Catholic youth had to tow in John Paul’s Church. Feeding the hungry was optional, a blind eye could be turned to death squads, but premarital celibacy was absolutely obligatory.

Realistically, virgin or not, you will never get a stadium full of sweaty youth to wildly cheer for chastity after five hours in the sun. When football matches lasted that long, guys would take the lucky condom out of their wallet, inflate it to maximum expression and let it fly. Just to cheer for the home team. Anyway, heads would roll. A direct, personal order from Rome. The Pope was pissed, and someone had to pay.

Diplomatic protocol required a meeting between heads of state. The organizers had to allow for a visit to Pinochet at La Moneda. John Paul couldn’t not shake the tyrant’s hand. Some people imagined that he would go to the presidential palace and demand an answer for the families of the disappeared. But that was never going to happen.

The team had warned the Holy Father not to step out onto the balcony with Pinochet, but he paid no attention. The Polish Pope was, perhaps, insensitive to the finer points of local politics, but he was no fool. He wanted to send precisely the message that the local church wanted him not to send. The balcony at La Moneda was the emblematic spot from which Presidents had addressed the crowds for a hundred years, the place where illustrious visitors were welcomed and presented to the cheering crowd. The photo of the Pope on that balcony with Augusto Pinochet traveled around the world, communicating his moral support for the dictatorship and all of its excesses.

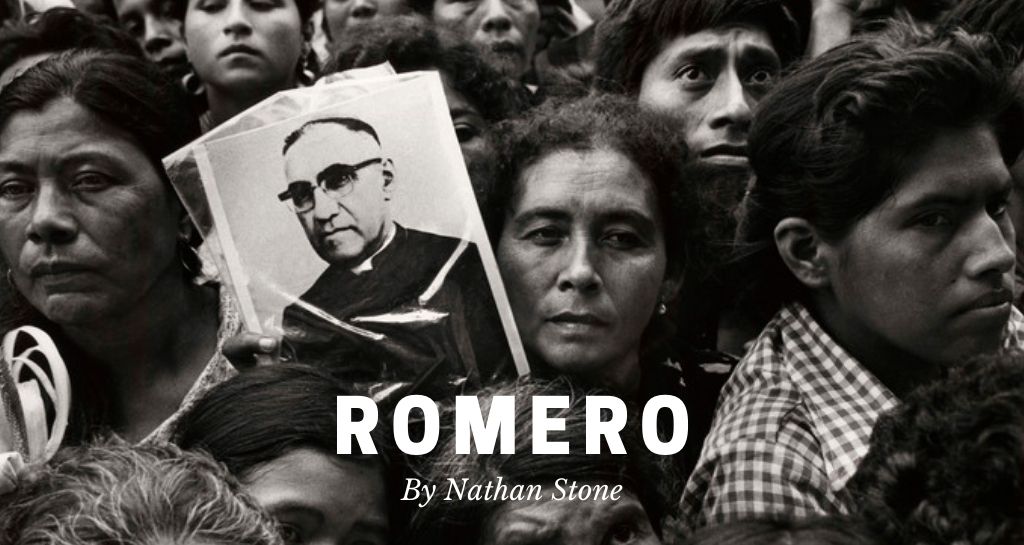

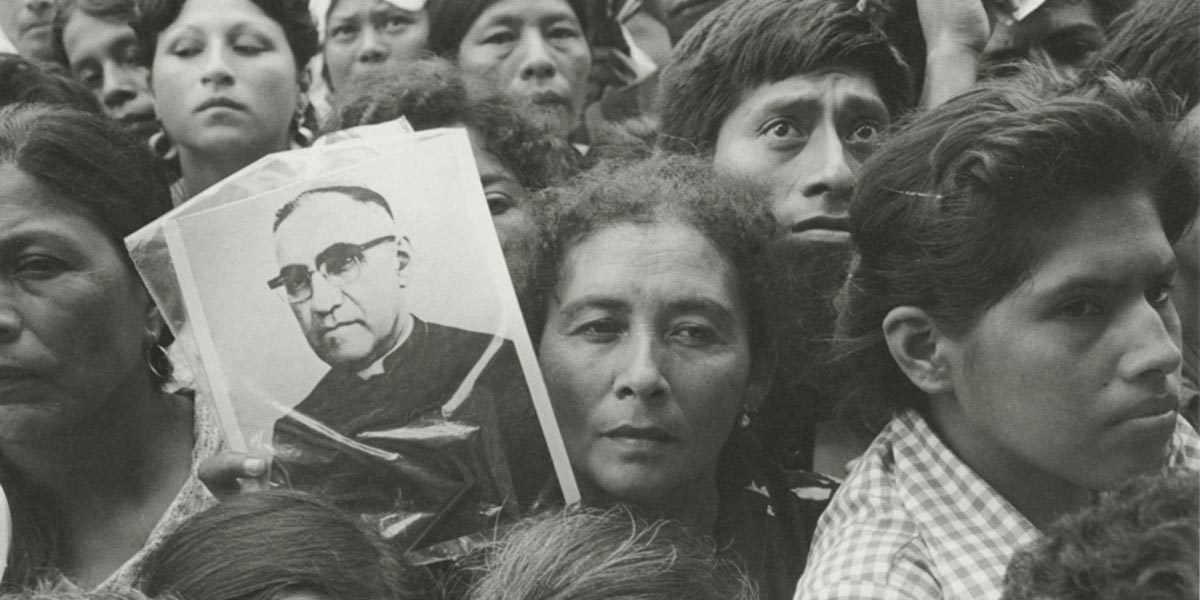

In December of ’79, Oscar Romero made a trip to Rome to speak with the Pope about priests who had been murdered in El Salvador. When the Holy Father discovered what the meeting was to be about, he canceled it. So, the Archbishop approached the Holy Father at a general audience to insist. It was his right as archbishop. The Pope finally received him. Romero showed the Holy Father pictures of a young priest who had been murdered by military death squads. His Holiness asked if perhaps that man was not also a guerilla fighter, assuming, in all is majestic infallibility, that if those brave soldiers had killed him, that he must have deserved it.

It was not a friendly meeting. The Holy Father ordered Monseñor Romero to strengthen the ties between the Church and the Salvadoran dictatorship. He said that Romero should see to the sacramental needs of Roberto D’Aubuisson his family because, in spite of what the Archbishop might think of D’Aubuisson’s regime, the Holy Father had heard from his trusted sources that the Salvadoran dictator was a practicing Catholic.

Within three months, Oscar Romero had been assassinated. It happened as he was celebrating Mass. The Vatican was silent. The authorities refused to recognize that he was a martyr. John Paul was the absolute authority in the Roman Catholic Church for 27 years, ten more than the rule of Pinochet. In that time, the Church lost all the credibility that it had earned on the street, with blood and sweat, after the Council, among the poor.

If the Holy Father had publicly shown some support for the Archbishop, if it had become clear to Roberto D’Aubuisson and his death squads in El Salvador that the Holy Father and all his cardinals in Rome would not tolerate the spilt blood of archbishops, they never would have touched him. Roberto D’Aubuisson was no fool. The cost would have outweighed the benefit. As it was, it seemed as if the death squads were doing the Holy Father a favor. Just like back in the good old days of excommunications, recantations, public beheadings and witch burnings.

Monseñor Romero had not always been a champion of the poor and oppressed. He was, in fact, quite a conservative young churchman, very orthodox in every way. He was comfortable in the old system; strict in his observances and rigorous in his demeanor. That was probably why he was chosen to be the Archbishop.

He became the shepherd of a fractured country. El Salvador in the ’70s was as tormented as it was tiny. He spoke to mothers who had lost their sons. He presided at the funerals of the young men executed in the street. He consoled the survivors of torture.

Then, they murdered his friend, a country priest. Father Rutilio Grande had served the poor. For Oscar Romero, that was the last straw. He wrote letters to President Carter, begging him, send no more weapons. They are killing my people. The US had a long tradition of bankrolling assaults on poor people. It was Standard Operating Procedure.

Romero asked the Holy Father for protection. The Holy Father directed him to embrace the authoritarian state. Roberto D’Aubuisson was still a young man. He liked to personally go on patrol with his death squads, to feel the thrill of squeezing off a few rounds and watching his victims bleed out. The Pope didn’t understand that. Or maybe he did. Maybe he thought it was a good thing. Maybe he really believed that D’Aubuisson was a local hero, a man to be honored, blessed and congratulated.

The Archbishop was gunned down while celebrating Mass. Time Magazine said that as he raised the chalice, the bullets hit him in the chest, that his blood mixed with the blood of Christ on the church floor. That’s not true. He was preaching. They killed him for what he said. For insisting that the massacre of the Salvadoran people had to stop.

That was March of 1980. It was a cool morning in Peñalolén when we heard the news on Radio Cooperativa. We had only been there about six months, and we were just beginning to understand what it meant to live in the shadow of a regime that had no qualms about killing its own. The Archbishop of El Salvador has died, they said. Like Thomas à Becket. After that, we knew that the Promised Land would not come cheaply, that it would cost everything we had.

There were good reasons to become a revolutionary, comrade. Winning or losing was not really the issue anymore. It’s just that we could no longer continue down the road we had been walking. Our new pilgrimage would have to take another path. Wherever it led us, that was where we would go, romeros in search of a saint we could believe in.

More From Nathan Stone:

Three-year-olds on the world stage

Underground Santiago: Sweet Waters Grown Salty

Related materials by Nathan Stone:

Taller: ¿Noticia, Opinión, o Propaganda?

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.