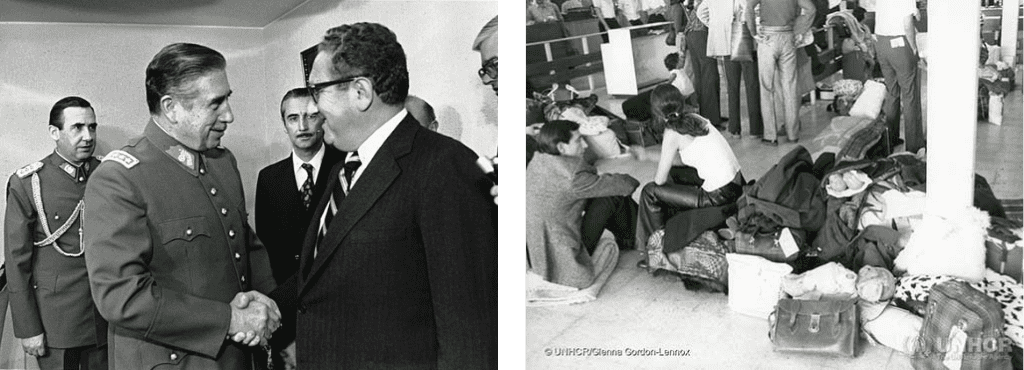

Official tallies put the death toll inflicted by the Pinochet regime in Chile over three thousand, while the imprisoned and tortured numbered over thirty-eight thousand. Not to mention almost two hundred thousand, one in every fifty Chileans, who went into exile. Staggering as those numbers might be, such statistics represent but a fraction of real victims. Most of the dictatorial blowback happened under the radar, in the clandestine shadowlands of the rural backcountry and deep within the interlocking borders of peripheral urban shantytowns, Chile’s poblaciones. There, resistance was subtle, solidarity was key, and no record survives. Chileans without friends in high places, those who lost their hearts, their hopes, and their lives in those forgotten corners, live on only in the memories of their friends, families, and neighbors.

I lived in Chile’s poblaciones for most of the 1980s, as the guest of a warm and complex community, skilled at stretching its meager resources in survival mode, and eager to share bread, shelter, and stories with a stranger. I saw how mothers kept their children fed with stale bread, a can of tuna and a tiny garden. I watched the household providers descend from genteel poverty to unemployed indigence, losing honor and self-respect in the process. I participated as a peer in the daily struggle of the lost boys who hung out on the street, excluded from work and school, marking their territory, kicking their soccer ball, and sharing their weed, while they waited to see what would happen next. The clan was ragged, sometimes, but highly structured in invisible ways. It was the closest I ever came to gang membership. Marcos Mellado, a handsome soft-spoken lad of twenty, commanded the covert allegiance of each and every one.

Marcos Mellado had five younger brothers. All of them belonged to his entourage. He was the real cacique. He was also my compadre. That was a specially charged term, a created relationship that intended to be as strong as any blood tie could ever be.

You couldn’t really have many compadres. Even one took a lot of time. Marcos didn’t have a child, not yet, and neither did I, so it wasn’t official. At first, being compadres was kind of a joke. We were so different. Then, hearts began to beat in rhythm, and it wasn’t a joke anymore. It was a magical connection, a bond thousands of years old. I couldn’t explain it, but I had to step up. You didn’t back down from that.

Marcos had a girlfriend. Her name was Andrea. Andrea’s father, oddly, had been a cop. He died one night when he came home drunk and the brick wall that he had built to keep the bad boys off of his lawn fell on him. They didn’t find him till the next morning.

Marcos and Andrea had been together since before the falling of the wall. Finally, they had a little boy in ’81. I was sick with hepatitis when Marcos told me about it. We agreed that, if I didn’t die, I would be the child’s godfather, and then, it would be official.

It was about then that Marcos’ parents requested asylum in France. They had to say they were being persecuted for political reasons. It wasn’t true, but France wasn’t offering economic asylum. They had just gotten tired of being so poor. The recession had hit them hard. They managed to round up some false testimonies. The French consul bought their story, and they went to France as refugees.

The parents took the two younger boys with them. Marcos became the head of the household, which consisted of his three remaining brothers and most of his friends. It was where everyone went, really. The house was small with a corrugated metal roof, but the back patio was spacious, with fruit trees, shade in the summer, and a few chickens. That was how they got by. Fruit, eggs and rice; then rice, eggs and fruit. If anyone got a hold of some money, the idea was to go to the street market and bring home the earnings in potatoes, beans or onions.

There was a campfire every night. There was always a song and a story. Sometimes, there was weed, wine or beer. One afternoon, in early autumn, el Torombolo fell asleep in a big pile of leaves. I think his name was Jorge, but no one ever called him that. Torombolo was the Chilean name for Jughead, from the Archie comics. Hours later, after dark, el Torombolo woke up with the cold night air and the strum of the guitar. It was startling to have a person suddenly jump out of a pile of leaves. Not long after that, he died.

El Torombolo sniffed glue. It was an awful drug. The boys could buy it at any hardware store. It was neoprene contact cement, and it was very toxic. The usual brand was Agorex, and that was what they called it. They would put a spoonful in a plastic bag and inflate it. Then, they breathed the vapors until it dried. It was very cheap. Users got very high and then, they weren’t hungry anymore.

Marihuana had the opposite effect. Smokers got hungrier. Some guys smoked, and then sniffed glue because they couldn’t find anything to eat. Neoprene destroyed the liver, the kidneys, and the brain. The damage was instantaneous, irreversible, and accumulative. Very few ever quit, and they all paid the price. El Torombolo was badly hooked and everyone knew it. They still loved him but he still died.

They said he died of a hot dog, but that wasn’t true. Well, maybe he did eat a hot dog from the kiosk. Those were pretty dangerous. He got a stomachache, and they took him to the ER at the Hospital Salvador. The medical students there tried to operate on him. If it had just been food poisoning, they could have pumped his stomach. I think the young doctors there tried to remove his gall bladder, but when they opened him up, they discovered that all his internal organs were necrotic. His life collapsed right there in the operating room.

It wasn’t the hot dog. It was the neoprene. And it was tragic. He will never appear on any list of the victims of the regime, but everyone knew that this was the sort of thing that happened when young men had nothing to do and nowhere to go. When there was no hope, no passion, no desire to live. Life under the military regime was emasculating, and Agorex was the answer to a collective death-wish. Part of the plan.

The wake was at his home. It was a very poor house with a dirt floor. That night, it became a mud floor with the flood of tears. His mother was inconsolable. His friends were all there. They had made a wreath of joints to lay on his coffin.

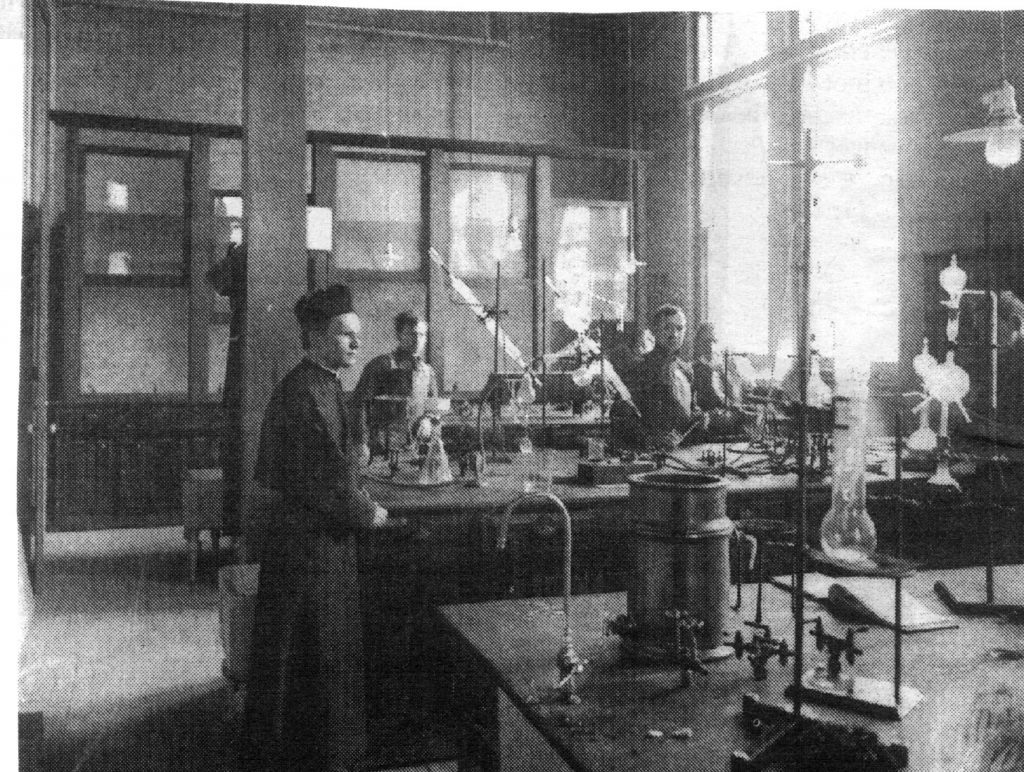

A Holy Cross priest invented neoprene after World War I. Father Julius Nieuwland was a professor and research chemist at the University of Notre Dame. Researchers were trying to create synthetic rubber for tires. You need tires to make wars, and all the rubber in the world, back then, came out of the Amazon. Because of this, the military machine was vulnerable to entangling alliances and possible future maritime blockades. Father Nieuwland created synthetic rubber and he became an overnight patriot. Neoprene never went into mass production for tires, but it found a niche in contact cement.

Nieuwland was born in Belgium. His parents emigrated to the US and found their way to the icy hinterland of South Bend where young Julius went to boarding school at then trendy Notre Dame. The Notre Dame experience began in middle school in those days. It was a free education for boys from poor immigrant farm families. Julius later joined the Holy Cross Fathers.

Before World War I, when Nieuwland was just a seminarian and graduate student of chemistry at the Catholic University in Washington, he was tinkering around with acetylene in the lab, and accidentally discovered lewisite, an important compound that would later be used in the production of chemical weapons. Poison gas. Nieuwland spent a few days in the hospital that time. He breathed a face-full of it, but he didn’t die.

Later, as a researcher at Notre Dame, he learned to stabilize the acetylene, and DuPont Chemical Company bought his patent. They used his research to develop and market neoprene, which became Agorex, contact cement intended for shoe repair. It was ironic. In Peñalolén, hell and salvation both came from the Holy Cross Fathers. They had unwittingly provided the glue for sniffing, in the same shantytown parishes where they supplied missionary pastors from Indiana to console the anguished souls with holy water and faint strains of liberation theology.

In Chile, more Agorex was sold for sniffing than for shoe repair. That was what killed el Torombolo. Blas read the prayers at the wake. He still belonged to the gang, but he had become a seminarian with the liberationist Holy Cross. Because of the tight social structure of the tribe, though, Marcos Mellado bore the weight of the collective sadness. He was their cacique. He should have been able to save el Torombolo, but there was nothing he could do. I think that was a turning point for him. After that, he began looking for a way to follow his parents into exile. When he departed, Chile lost one of its best and brightest. In Paris, Marcos played Chilean folk tunes on the sidewalks of Paris for pocket change.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.