By Cali Slair

In The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492, Alfred W. Crosby Jr. writes that, of all the diseases brought from the Old World “the first to arrive and the deadliest, said contemporaries, was smallpox.”[1] Smallpox is a contagious, disfiguring, and potentially fatal disease whose origin in Europe can be traced as far back as 300 CE, with some researchers noting evidence of a smallpox like virus even earlier, in Egyptian mummies, around 1157 BCE. On May 8, 1980, the World Health Assembly officially declared that smallpox was eradicated, making it the first infectious disease to reach a global prevalence of zero due to human efforts. The eradication of smallpox was made possible through global vaccination campaigns and surveillance led by the World Health Organization’s Smallpox Eradication Programme (1966-1980).

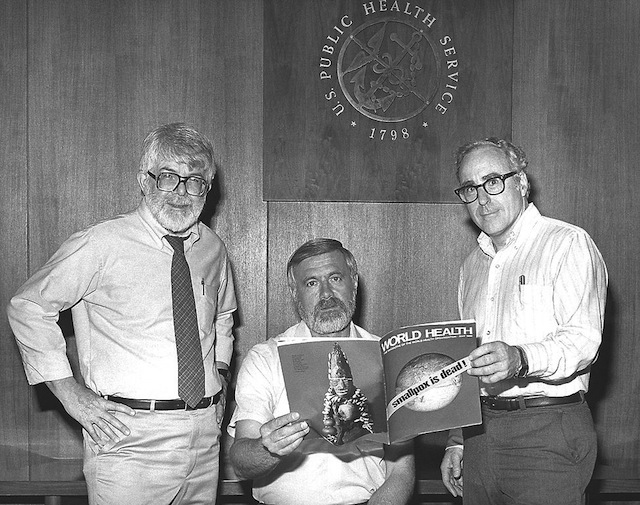

This 1980 photograph taken at the Centers for Disease Control, depicted three former directors of the Global Smallpox Eradication Program as they read the good news that smallpox had been eradicated on a global scale. From left to right, Dr. J. Donald Millar, who was Director from 1966 to 1970; Dr. William H. Foege, who was Director from 1970 to 1973, and Dr. J. Michael Lane, who was Director from 1973 to 1981. Via Wikipedia.

While May 8, 1980, is often celebrated for marking the eradication of smallpox, members of the Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication actually concluded that smallpox had been globally eradicated in December 1979. This commission consisted of a team of twenty-one distinguished doctors from around the world such as the Deputy Minister of Health of the USSR, the Dean of the School of Health and Hygiene at Johns Hopkins University, and the Director-General of the National Laboratory of Health in France to name a few.

This young girl in Bangladesh was infected with smallpox in 1973. Freedom from smallpox was declared in Bangladesh in December, 1977 when a WHO International Commission officially certified that smallpox had been eradicated from that country. Via Wikipedia.

The success of the Smallpox Eradication Programme meant the removal of a disease that had threatened human beings for thousands of years and claimed the lives of millions. There were approximately 300 million smallpox related deaths in the twentieth century alone. Although smallpox cases were extremely rare in North America and Europe by the mid-twentieth century, in 1967 smallpox was still prevalent in 33 countries in Africa, Asia, or South America. In 1967 alone there were approximately two million smallpox related deaths. Consequently, it comes as no surprise that the Smallpox Eradication Programme is considered to be one of the WHO’s greatest achievements. Following the successful eradication of smallpox, campaigns for the eradication of other infectious diseases gained support. Unfortunately, only one other disease, rinderpest, which affects livestock, has been eradicated since 1980.

While the smallpox virus has been eradicated for decades, smallpox continues to attract popular and scholarly attention today. One of the main topics is the debate between the WHO, the United States, and Russia on whether to destroy the last remaining live smallpox virus stockpiles. While the WHO originally called for the live virus stockpiles to be stored by the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta and the State Research Institute for Viral Preparations in Moscow, since 1990 the WHO has called for the destruction of the last remaining stockpiles on the basis that they are no longer necessary for public safety, diagnostics, vaccines, or genome sequencing. The U.S. and Russia have continued to reject and postpone the implementation of this declaration since the start, arguing that the live virus is necessary for further research and the development of new medications even though DNA sequencing of all the known live virus stocks is complete. As a result the WHO has assembled three different committees to settle this debate.

The unexpected discovery of the live smallpox virus at various unauthorized laboratories has piqued interest in the security of the stockpiles. Furthermore, in 1992 a high-ranking official in the Soviet biological warfare program revealed that during the Cold War the Soviet Union had developed a highly lethal strain of the smallpox virus as a biological weapon and had secretly stored a large amount of the virus. In 1993 Russia moved its stockpiles without receiving prior authorization from the WHO. The WHO technically controls the stockpiles and entrusts the U.S. and Russia to store the stockpiles but, without the means to enforce its call for destruction, the WHO may find it difficult to ensure U.S. and Russian compliance with its final recommendation.

Why are the live virus stockpiles such a big deal? The main concern of “destructionists,” those in favor of destroying the stockpiles, is the possibility of laboratory-associated exposure, accidental release, or theft or purchase of the live virus by terrorists. Given that the smallpox virus is easily spread and potentially fatal, the risk that terrorists could acquire the live virus and use it as a biological weapon is a valid concern. Furthermore, the fact that smallpox vaccination ceased after its eradication makes its potential as a biological weapon even more grave. Nevertheless, the WHO has made remarkable strides in improving public health with its Smallpox Eradication Programme and will undoubtedly continue to call for efforts to help ensure public safety and limit the potential for exposure of the virus it worked so hard to eradicate.

You may also like:

Jonathan Hunt’s review of David E. Hoffman’s The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy.

[1] Alfred W. Crosby Jr., The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492 (Westwood: Greenwood Press, 1972), 42.