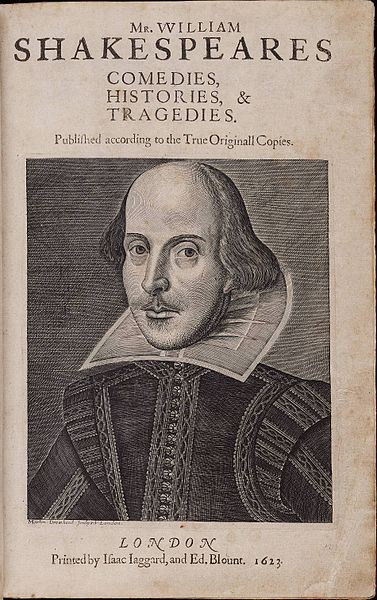

Matthew Restall’s When Montezuma met Cortés delivers a blow to the basic structure of all current histories of the conquest of Mexico. Absolutely all accounts, from Cortés’ second letter to Charles V in 1520 to Inga Clendinnen’s masterful 1991 article “’Fierce and Unnatural Cruelty,’”[1] assume that the conquest of Mexico was led by Hernán Cortés, who is described by Wikipedia as a “Spanish Conquistador who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of what is now mainland Mexico under the rule of the King of Castile.” These accounts represent Cortés as willingly deciding to enter Tenochtitlan in the hopes of capturing Montezuma, the Aztec Emperor, expecting to rule Mexico via a proxy ruler, and seeing himself as Julius Cesar in Gaul. Although Clendinnen shows that there was no Machiavellian logic in any of this Cortesian strategy, she keeps the trope of Cortés as the central protagonist of a tragic-comedy.

Montezuma’s reasoning for allowing Cortés and his 250 surviving conquistadors to enter Tenochtitlan is, after Cortés’s overblown heroics, the second leg of all histories of the conquest. Montezuma’s actions have been cast as a surrender to prophecy, implying imperium translatio (willingly bestowing sovereignty upon superior returning deities), idiotic cowardice, or simply unfathomable, unintelligible reaction. Either way, Montezuma always comes across as a diminished ruler, even a puppet. Cortés captured, imprisoned, killed, and desecrated Montezuma’s remains.

The third leg of the stool organizing narratives of the conquest of Mexico is the brutality of Aztec rule and the extent of the Aztec practice of human sacrifice. The alleged industrialization of Aztec ritual sacrifice has allowed some traditional accounts to justify the conquest.

Restall knocks down all three legs. He demonstrates that the numbers of sacrificed captives that are thrown around make absolutely no sense. The proposed numbers do not match basic arithmetic, demography, or the archeological findings at templo mayor, where the sacrifices were supposed to have taken place.

The leg that sustains Cortés as protagonist tumbles down just as easily. Restall demonstrates that Cortés was a mediocrity before landing in Yucatan and after the conquest. Cortés arrived in Hispaniola in 1504 and participated in the conquest of Cuba in 1511, playing the role of follower not leader throughout. After Tenochtitlan, Cortés led the conquest of Honduras and California where his incompetence shined through, not his greatness. Restall shows that leaders of the many Spanish factions, namely, the captains, bosses of family/town share-holding companies, who in Mexico made all key decisions, not Cortés.

Finally, the leg in the stool that portrays Montezuma as fool, is demolished by Restall in showing that Montezuma made fools of Cortés and his captains. He led them down a path that would secure attrition and observation. The envoys of Montezuma in Yucatan encouraged a path to Tenochtitlan via an enemy route. Cortés and his captains encountered first the Totonec and then the Tlaxcalan, before crossing the mountains to get to the valley that nestled Tenochtitlan in the middle. Restall demonstrates that when the weakened conquistadors stopped fighting with the Tlaxcalan, it was the latter,, not Cortes, who chose the path to get to the Aztec capital to visit Montezuma, including a detour to the city of Cholula.

This detour has always puzzled historians because it was out of the way and because the “conquistadors” staged a massacre of Cholulan lords for no apparent reason whatsoever. In his letters to Charles V, Cortés sought to explain the massacre as preventive violence to clamp down on the simmering rise of treasonous behavior among allies. Restall shows, however, that the massacre was a Tlaxcalan initiative and that the Spaniards had no role in its planning.. Tlaxcalan elites massacred the Cholulan for having recently broken the Tlaxcala Triple Alliance (that also included Huejotzingo) in order to embrace the Aztec. Even in their massacres, Cortés and his captains were puppets.

Restall dwells on Montezuma’s zoos and collections to provide an answer to another puzzling decision of Cortés and his captains: they disassembled their fleet in Veracruz and crossed Central Mexico to dwell in Tenochtitlan for nine months. What would 250 badly injured and poorly provisioned conquistadors expect? To rule an empire of millions from the capital by holding the emperor hostage? Ever since Cortés penned his letters to Charles V, chroniclers and historians, (including indigenous ones trained by the Franciscans who wrote accounts of the conquest in the 1550s for the great multi-volume encyclopedia of Aztec lore, the Florentine Codex) have accepted this as a plausible strategy, even a brilliant Machiavellian one that took Montezuma unaware. Restall, however, proves that the Spaniards remained nine months walled in Montezuma’s palaces near the monarch’s zoo and gardens.

Restall proves that Montezuma’s majesty resided in his collection: zoos, gardens, and pharmacopeias. Montezuma collected women, wolves, and dwarfs. He led Cortés and his bosses to Tenochtitlan to add the pale Spaniards to his menageries and palaces. The Spanish factions had no choice. Montezuma was no one’s puppet. He used the Spaniards as curiosities to reinforce his majesty and power. Montezuma was no one’s prisoner; he was murdered. His body never desecrated by his own people. After the murder, the Spaniards were slaughtered and the few survivors fled the capital in the middle of the night, humiliated and beaten. The historiography has called the night when the Aztecs routed the Spaniards the Noche Triste.

Cortés and his surviving captains reassembled after the rout in Tlaxcala, from where they allegedly led a year long assault on Tenochtitlan. Restall shows that this protracted, final battle over the capital and the surrounding towns was not a campaign Cortés; captains controlled, any more than they controlled the first visit to Tenochtitlan. The final siege of Tenochtitlan was a war among noble Nahua factions as well as the reshuffling of altepetl (Nahua city) alliances. Elite families of Texcoco realigned to create a new alliance with Tlaxcala.

Restall introduces a new category to replace conquest: war. He equates the violence unleashed by the arrival of conquistadors with the violence of the two World Wars in the twentieth century. There was untold suffering and civilian casualties, systematic cruelty by ordinary people, rape and sexual exploitation as tools of warfare.

He is right. Yet this shift, paradoxically, infantilizes the natives and concedes all agency, again, to Europeans. In the political economy of malice, Spaniards had no monopoly. Restall demonstrates that Tlaxcalan and Texcocan lords led the massive massacres in Cholula and Texcoco. It is clear, also, that lords used the war to transact women like cattle and to amplify the well-entrenched Mesoamerican system of captivity and slavery. Why then does Restall concede to the Spaniards all the monopoly of cruelty? War made monsters not just out of ordinary vecinos from Extremadura and Andalucia. War also made monsters of plenty of local lords.

[1] Inga Clendinnen “Fierce and Unnatural Cruelty”: Cortés and the Conquest of Mexico, Representations 33 (1991): 65-100

Other Articles You Might Like:

Facing North From Inca Country

No More Shadows: Faces of Widowhood in Early Colonial Mexico

Purchasing Whiteness: Race and Status in Colonial Latin America

Also by Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra:

From There to Here: Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra

Puritan Conquistadors

Jerónimo Antonio Gil and the Idea of the Spanish Enlightenment